Monday, January 19, 2009

In Praise of Paul Blart (Updated, January 21)

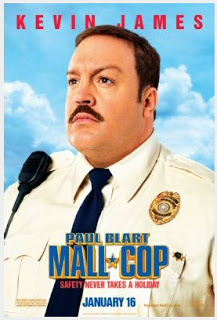

It’s funny, ’cause it’s true: Paul Blart, the unarmed mall security guard hero of the new film, is a more suitable exemplar of the “protect and serve” ethic than the government’s armed enforcement agents.

When tyrants rule, jesters often boldly tell truths that falter on the lips of fear-plagued philosophers. Perhaps this explains why, amid the consolidation of a totalitarian Homeland Security State, it fell to Kevin James, gifted comic actor, mixed martial arts fan, and cinematic role model for economy-sized American men, to put into play the notion that we would be better off doing away with government police forces outright, and entrusting security to private citizens and entrepreneurs.

James co-wrote, co-produced, and stars in the new movie Paul Blart: Mall Cop, a modestly produced family comedy whose immense opening weekend success (it took in something north of $34 million, or nearly twice what the studio expected) surprised everyone but the viewing public. Dismissed by most professional critics but warmly reviewed by paying customers, the film displays every indication of becoming the sleeper hit of Hollywood’s post-Christmas discard season.

I earnestly hope the film generates a wave of positive word-of-mouth, not only because it is a nearly ideal family film — genuinely funny and engaging, wholesome without being insipid — but also because it is gently subversive in promoting the idea that the increasingly militarized government law enforcement system is at best useless.

The audience meets the titular protagonist during fitness trials for applicants to the New Jersey State Police Academy. Short, chubby and visibly on the cusp of middle age, Blart is surprisingly athletic, blowing through the obstacle course with confidence where younger, less motivated applicants falter. But Blart falls just a few feet short of his objective as he is immobilized by a hypoglycemic blackout — a condition that will plague him throughout the story.

Like many of us whose gravitational profile is less than optimal, Blart has an unfortunate habit of treating food as a refuge from life’s indecencies. A single parent to an adorable child (the mother, an illegal immigrant, abandoned father and daughter once her foothold in the U.S. was secure), Blart works long hours as a mall security guard (he prefers the term “security officer,” but

allows that there is some controversy over the proper designation).

Customer service: In a scene from earlier in the film, Officer Blart takes a moment to help a small shopper with a problem.

Owing to his girth, his habit of patrolling while mounted on a Segway-style personal transporter, and — let’s be candid — his job, Blart endures what sometimes seems like an incessant onslaught of demeaning, even emasculating moments. But he remains cheerful, helpful, and generous, doing whatever he can to make things easier for the paying customers.

While he speaks often about protecting the safety of mall patrons and merchants, it’s clear from his actions that he understands the importance of facilitating commerce. Unfortunately, Blart aspires to be a state trooper, which might explain some of the mistakes he makes early in the film — such as threatening to issue a “speeding citation” to a senior citizen in a motorized wheelchair, or to make a “citizen’s arrest” of a turbulent woman at Victoria’s Secret.

The latter incident ends with the woman — whose size and body composition are similar to Blart’s — thrashing the hapless security guard, not because Blart is unable to handle her but because he simply will not, under any circumstances, assault a woman.

The civilized self-restraint displayed by this fictional security guard contrasts very well with the documented behavior of too many real-life government police hooligans.

He’s scared, but he’s not running away: Officer Blart conducts a recon of the hostage site (left), and leads several pursuing robbers into an ambush (below, right).

While making his rounds just prior to Thanksgiving, Blart has what movie people call a “meet cute” with a pretty wig merchant named Amy, but the romantic possibilities initially appear to be stymied by developments I won’t describe here.

When “Black Friday” — the day after Thanksgiving, the busiest retail shopping day of the year — rolls around, Blart is at his post, helping the gears of commerce turn smoothly. A video arcade proprietor, eager to go to the bank before it closes down, asks Blart to “mind the store” briefly. Blart is thus lost in the aural jungle of video game noises when a crack team of armed robbers shut down the mall, drive out the paying customers, and seize hostages at the bank — including Amy.

When the cops arrive, their tentative and by-the-books effort to enter the mall is quickly repulsed. The police contact Blart, tell him about the hostage situation, and urge him to join them behind a secure perimeter. As he reaches the exit, Blart espies something that forces him back inside: Amy’s 1965 Ford Mustang.

Blart doesn’t know exactly what he will do, but he’s not about to leave Amy in the hands of the criminals. So, in violation of the Prime Directive for government police — “officer” safety uber alles — Blart screws up his courage to a sticking place, downs the contents of a Pixie Stick to ward off hypoglycemia, and heads back into the mall to confront the evildoers.

Not only is this a satisfying dramatic choice by the protagonist — who at this point officially becomes a hero, whatever the outcome — it also acts as an oblique rebuke to the familiar police approach to hostage situations: Call in the SWAT team, which will take forever establishing a “secure perimeter” while innocent, unarmed people are at the mercy of armed criminals.

Middle-aged portly guys REPRE-SENT! In a scene straight out of Kingdom of the Crystal Skull or Quantum of Solace, the Blartster takes down a bad guy, sending the two of them crashng through a skylight and hurtling from a lethal height. (Don’t worry, their fall is broken in a family-friendly way.)

After Blart decides to rescue the hostages, the film becomes a family-friendly but surprisingly tense palimpsest of Die Hard, as Blart out-thinks, out-maneuvers, and out-fights the robbers, who are a pack of feral X-athletes. “The mind is the only weapon that doesn’t need a holster,” Blart tells a trainee earlier in the film (who appears later in a somewhat surprising capacity). Blart’s mind is whetted to a fine edge by his desire to protect something in which he was fully invested — the task of protecting a business he valued, a woman with whom he might fall in love, and eventually his daughter, who finds herself among the hostages later in the film.

Describing the film beyond this summary would take us into spoiler territory. Suffice it to say that the third act did something I hadn’t expected, and was delighted to see: It depicted the utter uselessness of the paramilitary goon squads called SWAT teams in dealing with hostage crises, and actually offered a compelling illustration of the opportunities for corruption presented by militarized law enforcement.

I will spoil one element of the ending: Offered an immediate posting to the New Jersey State Police, Blart turns down government “work” in favor of what he decided is his true calling — protecting the businesses of the shopping mall and the people who spend their hard-earned money there.

It was that final development that elevated Paul Blart: Mall Cop onto my list of vital anti-government films. That list includes Ghostbusters, whose villain, Walter Peck, was a bureaucratic eunuch employed by the EPA, and The Simpsons Movie, in which the villain is the entire federal government, as embodied by a deranged corporatist named Russ Cargill (“Sir, I’m afraid you’ve gone mad with power,” cavils an underling, to which Cargill replies that it’s boring to go mad without power, since “no one listens to you”), who heads the EPA.

In a less worthy film, Blart would have accepted a government job as a due “reward” for his heroism, thereby graduating from mere private sector work into the exalted realm of official coercion. This is the payoff for which audience expectations had been prepared — and having the character decline it is a pretty bold statement, albeit probably an unintended one, about the superiority of commerce and private means of security and dispute-settlement.

Other delicious touches season this unexpectedly tasty cinematic offering. The swaggering, gravel-voiced SWAT commander, who shoulders everyone aside and militarizes the hostage stand-off, is revealed to be a middle-aged, unreformed High School bully — and then something even more unsavory. Given recent scandals in New Jersey involving both corrupt and inept SWAT teams, this depiction is likely to resonate with at least some residents of the Garden State.

Paul Blart: Mall Cop is co-produced by Kevin James and Adam Sandler, who have a lot to atone for after inflicting I Now Pronounce You Chuck and Larry upon the public. They’ve made a solid downpayment by creating this delightful film, which is both terrifically entertaining and commendable for finding the dignity and even heroism in a private security job that is easily mocked but in principle superior to the state’s alternative.

Rather than permitting the State — the enemy of all human prosperity and social progress — to monopolize and militarize security functions, we should be dis-establishing government police mechanisms as rapidly as possible and relying on private means (beginning with ubquitous civilian firearms ownership) to provide security for persons and property.

Alas, in the real world we’re forced to inhabit, Officer Blart would either be shoved aside by, or assimilated into, some militarized monstrosity like the corporatist (which is to say fascist) police force that patrols Oakland’s BART (Bay Area Rapid Transit) system. The BART police earned tragic notoriety on New Year’s Day owing to the unprovoked lethal shooting of Oscar Grant III, a helpless, unarmed, cooperative young man who was face-down and surrounded by police on a subway platform.

***

***

This homicide — merely the most recent in a string of needless killings by Oakland’s BART police, a “public-private police partnership” in the worst sense of the expression — provided a horrifying reminder that the murderous tactics and official corruption common in government law enforcement quickly infect any nominally private entity seduced into such a “partnership.”

Prior to the advent of cellphone cameras, The BART police had been able to cover up and dismiss four very suspicious lethal shootings. The Grant shooting, however, occurred in the YouTube age, which means that this entirely avoidable killing was added to the large and growing corpus of evidence that police today see themselves as, and behave like, an army of occupation — and the BART police force’s familiar cover-up tactics weren’t successful.

Paul Blart: Mall Cop is an exercise in cinematic whimsy. But the need for our society to embrace genuinely private security arrangements is a deadly serious one: The state’s armed enforcers are rapidly becoming a caste apart from, and supposedly superior to, the public they supposedly serve. Facile as it may seem to say so, it can properly be said that, where maintaining public order is concerned, we are presented with a choice between Blart and BART.

Update, 1/21 —

David Codrea, who compiles the utterly indispensable War On Guns blog, expresses understandable concerns that Paul Blart: Mall Cop is extolling the value of “unarmed protectors” and peddling the reliably lethal myth that “arms are superfluous when confronting violent evil-doers.”

As indicated in the very first caption to the essay above, I do think the character of Paul Blart, the central figure in what is, after all, “an exercise in cinematic whimsy,” embodies the “protect and serve” ethic, but this isn’t because he’s unarmed; it’s because he’s willing to confront the predators immediately, with whatever he can seize upon as a weapon, rather than huddling behind a heavily armed perimeter, as police generally do in hostage situations, waiting for the overkill factor to be high enough to ensure officer safety.

Firearms are vitally important in dealing with malefactors of all varieties. The most dangerous armed criminals are those employed by the state. This is why I was so struck by the fact that the Blart character actually turns down a chance to join the police (read: occupation) force at the end of the film.

While I reject civilian disarmament with every molecule of my being, I’m willing at least to chew on the notion that civic order would be improved if we were to disarm the police, at least while they’re acting in an official capacity. There really is no institutional substitute for the practce of armed self-defense.

A quick personal note —

I want to thank everyone who has suggested names for the Grigg family’s newest member, who is scheduled to arrive on or around February 6. Korrin and I are really stumped by this one, and we appreciate both your input and your very generous kind wishes.

On sale now!

Dum spiro, pugno!

Content retrieved from: http://freedominourtime.blogspot.com/2009/01/in-praise-of-paul-blart.html.