Wednesday, January 27, 2010

Killing the Commissar: The Limits of Submission

Sic semper Tyrannis:

Israelite liberator Ehud slays the tyrant-king Eglon.“… Ehud made him a dagger which had two edges, and he did gird it under his raiment upon his right thigh. And he brought [a] present unto Eglon, the king of Moab…. And Ehud put forth his left hand, and took the dagger from his right thigh, and thrust it into [Eglon’s] belly….”

Judges 3:16-21, describing the assassination of Moabite tyrant Eglon by the “deliverer,” Ehud the son of Gera

Even by local standards, the late Li Shiming was an uncommonly malicious “public servant.” His unabashed rapacity and casual sadism eventually cost him his life. Like the ancient Moabite tyrant-king Eglon, Li was stabbed to death without warning in an unlikely setting — a public school, in his case, rather than a summer parlor — by a young man many of his erstwhile victims consider a heroic deliverer.

As regional commissar in the northern China town of Xiashuixi, Li confiscated land and other property at will and terrorized anybody who expressed an audible objection. Notes Jane MacCartney, Beijing correspondent for the London Times: “One villager who got into a row with him over the allocation of a contract was beaten so badly that he suffered a fractured spine. He was beaten again when he arrived at [the] hospital.”

Zhang Weixing, a 58-year-old farmer, was among the scores or hundreds of people whose lands were confiscated by Li and distributed to the commissar’s cronies. Zhang and his wife did what they could to defend their pitiful little plot of land; for their trouble they were beaten by a mob of hired thugs.

Tyrannicide: Zhang Xuping, seen here in Beijing, confessed to killing a regional commissar in order to end his reign of terror. Zhang, 19, now faces the death penalty.

Similar treatment was visited on another local farmer named Zhang Huping (no relation), except that in his case the hired thugs were part of the official police force.

Zhang — whose mother was imprisoned by Li, and who was vindictively expelled from school on the commissar’s orders — was routinely assaulted and detained on fraudulent criminal charges in retaliation for his role in organizing farmers whose orchards were seized and destroyed in 2003.

“Li lorded it over Xiashuixi, an arid mining region where farmers struggle to find water to grow vegetables to sustain themselves or corn to feed their pigs,” recounts MacCartney. “His position as a local party boss gave him the power to run the district like a fiefdom.”

Among Li’s victims was a former childhood friend named Li Haiqing, who displayed astonishing strength of character by refusing to collaborate in the commissar’s crimes, despite promises of complete impunity.

“Li Shiming said that if he [Li Haiqing] beat someone to death and was sentenced to be executed he could use his influence to make sure he would be all right,” recalls Li Haiqing’s wife. “My husband refused. And this is what happened to him.”

“This” refers to the fact that Li Haiqing, after being arrested six times in retaliation for his refusal to work as one of the Commissar’s enforcers, was beaten so severely that he can no longer walk or talk. Not satisfied to see his erstwhile friend crippled, Commissar Li used his official connections to shut down every business Li Haiquing attempted to build.

Commissar and Chum: Li Shiming, left, poses with his childhood friend, Li Haiqing — a man whose life the Party functionary eventually destroyed.

Li was entirely typical of the local functionaries who represent China’s collectivist ruling caste — or, for that matter, the tax-devouring class afflicting any country, our own emphatically included.

While China has migrated in the direction of a market economy, the commissars and “princelings” who run the political system still exercise formidable power to enrich themselves through simple plunder. Their current economic model is a form of corporatist crony capitalism strikingly like the one prevailing in the USA, albeit with what Party ideologists call “Chinese characteristics.”

In the People’s Republic, the politically entrenched parasite class is making extensive use of the institutionalized larceny called “eminent domain” to confiscate property for their benefit.

“Chinese local governments in cahoots with developers have become infamous for forcibly seeking to evict residents from their homes with little compensation and often without their consent,” reports the Wall Street Journal. The holdouts are known as `nail households,’ since their homes are sometimes left stranded in the middle of busy construction sites. More often, however, they are driven away by paid thugs.”

This kind of thing never happens here in Lee Greenwood’s America.

Well, maybe it happens every once in a while.

Actually, it takes place all the time.

The Journal‘s description of Chinese corporatism at the local level brings irresistibly to memory the case of Lauren Canario, a freedom activist who was kidnapped by rented thugs — better known as officers of the New London, Connecticut police department — for refusing to vacate property that had been stolen through eminent domain on behalf of a federally subsidized “public/private partnership” (that is, fascist entity) called the New London Development Corporation (NLDC).

Lauren was not a trespasser; she was visiting the property with the permission of its owner. However, the NDLC had decided to swipe the land and give it to the Pfizer corporation, and this act of vulgar theft received the imprimatur of the Supreme Court. Lauren was arrested, imprisoned for months, and — in a touch that would have earned the admiration of Soviet or Chinese commissars — repeatedly subjected to psychological evaluation.

The “nail households” were razed, the Pfizer plant was built, and all of the expected payoffs were consummated. Then the economy collapsed, and Pfizer decided to shut down the facility and move its employees elsewhere, leaving behind a rotting and useless building constructed on stolen land.

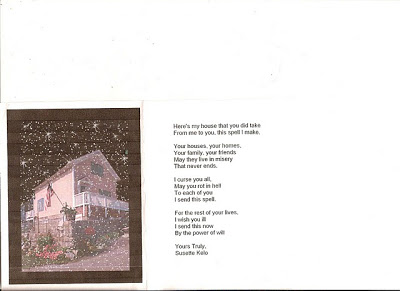

(Click to enlarge.)

In December 2006, Susette Kelo, the lead plaintiff in the unsuccessful lawsuit to prevent the NLDC’s larceny, sent the thirty people most deeply involved in that crime (a clique that could be considered a New London analogue to the Thirty Tyrants of Attic antiquity) a Christmas card that conjured every species of misfortune and hardship as punishment for their crimes.

As former real estate developer Don Corace writes in his recent book Government Pirates: The Assault on Private Property Rights and How We Can Fight It, Susette Kelo’s experience is entirely typical of the afflictions being visited on nominal property owners nation-wide — people who suddenly and unexpectedly collide with the grim reality that what they own can be seized at any time by those with abundant political connections and no identifiable scruples.

“Arrogant and corrupt city and county officials — with near limitless legal budgets … continue to align themselves with well-heeled developers, political cronies, and major corporations to prey on the politically less powerful and disenfranchised, particularly minority communities,” summarizes Corace.

Eminent domain “abuse” (if that word applies to a perfectly predictable application of an innately illegitimate power) is just one of many ways that property can be blatantly stolen through political means: “Through local zoning and the regulation of wetlands and endangered species, governments take property without compensating owners and also extort land and money in return for approvals.”

This is, of course, exactly the same racket being run by local commissars in the People’s Republic of China. It is interesting, and somewhat unsettling, that Chinese people for whom the concept of private property may be a relatively new and exotic concept seem to have a better understanding of what is happening than do their American counterparts.

Rebellion against eminent domain: A Navi fights back in the film Avatar.

This is why the current sci-fi epic Avatar resonates so powerfully with Chinese film audiences.

The film — derided by some as a pastiche of Pocahontas and Dances With Wolves, with a beat or two borrowed from Star Trek: Insurrection — depicts a desperate battle by aliens on a distant world to defeat human occupiers bent on seizing their most sacred land on behalf of a rapacious corporation. Considered by many American conservatives to be a paean to pantheist environmentalism, Avatar has been embraced in China as a parable of righteous rebellion by long-suffering, peaceful people against corrupt authority.

In Hong Kong, notes the Wall Street Journal, the film has served as a rallying point for “antigovernment activists trying to defeat a plan to demolish a village to make way for a new high-speed railway line. One mysterious benefactor reportedly donated movie tickets to the villagers to stoke their determination for protests.”

As commentator David Boaz correctly notes, Avatar could be considered “a space opera of the Kelo case,” a sci-fi parable denouncing blatant theft through eminent domain (or, what’s much the same thing, the orgy of political theft celebrated today as “Manifest Destiny” — which could be considered eminent domain practiced on a continent-spanning scale).

What can people do when everything they have can be seized at the whim of a ruler, without peaceful means of recourse or redress? Obviously, it is morally correct and, eventually, necessary in practical terms to defend one’s property by force. But is the contract killing of a deeply corrupt, entrenched official a form of self-defense?

Zhang Huping, having exhausted the peaceful means at his disposal, hired a teenager named Zhang Xuping (once again, no relation; apparently, “Zhang” is the Chinese equivalent of “Jones”) to kill Commissar Li.

Zhang approached the student with the proposition after noticing that the official routinely left his bodyguards behind when he visited the local school. In September 2008, the teenager — for a fee of roughly $150 — carried out the act by stabbing Li in the heart when he visited the school in September 2008. The mortally wounded commissar staggered into the parking lot, his last breath escaping as he reached the Audi luxury SUV he’d purchased with wealth pilfered from some of China’s poorest peasants.

The news that Li had died after being stabbed in the heart provoked widespread astonishment in the district — not that the commissar had been killed, but rather that, in defiance of reasonable expectations, he was in possession of an actual human heart. Otherwise, the populace was unmoved by the news that the execrable functionary had paid his debt to nature.

“I didn’t feel surprised at all when I heard that Li Shiming had been killed because people wanted to kill him a long time ago,”commented resident Xin Xiaomei. “I wanted to kill Li myself but I was too weak.”

The teenage Zhang was tried and convicted of murder, and sentenced to death. Capital punishment is usually carried out expeditiously in the People’s Republic of China, and Zhang would most likely have been killed quickly and quietly but for the fact that nearly 21,000 residents of the district signed a petition demanding clemency. That petition attracted public attention to the case, but probably won’t deter the ruling Communist Party from executing Zhang before his 20th birthday on February 25.

Interestingly, “corruption” is a capital offense in China; functionaries who enrich themselves without Party approval are sometimes put to death. Since Party officials were aware of the extent of Li’s depredations, his crimes had their tacit approval, at least until he injured the interests of a comrade with more political clout than he had.

Under the terms of Chinese law, it’s more accurate to say that Zhang didn’t “murder” Li, but rather privatized the imposition of the penalty for the commissar’s crimes. This will avail the young man exactly nothing, of course, but this fact offers yet another illustration of the consummate lawlessness of the regime under which Zhang and Li’s other victims were sentenced to live.

Despicable as Beijing’s ruling class is, the one tormenting our own country is even worse — not merely because its hypocrisy makes its crimes all the more odious, but also because of the global impact of its malign ambitions. Beijing, after all, hasn’t invaded and occupied countries on the other side of the planet, or deployed heavily armed drones over distant skies to kill unsuspecting people by remote control.

The corruption embodied by Li Shiming took root in the midst of China’s economic boom. The commissars who populate our ruling class will most likely make their presence most keenly felt as our economic collapse accelerates. This will reduce conflicts over property rights to its most elemental level. To borrow a line from one of my favorite films, things are likely to get terminal in a hurry.

As someone with an unconditional commitment to the non-aggression principle and the sanctity of each individual human life, I’m finding it exceptionally difficult to justify the killing of Li Shiming. Loathsome as he was, I cannot imagine confronting him — unarmed, defenseless, and unwary — and driving a knife into his chest. My reaction to such an opportunity would probably be akin to that of Starbuck staying his hand as he looked on the sleeping, helpless Captain Ahab, or (what’s much the same thing, as Melville pointed out) Hamlet declining to kill Claudius while the murderer was praying.

Of course, I didn’t live under Li’s reign, and so my reaction might be less an illustration of the strength of my principles than the weakness of my imagination. There are limits to what people can endure, and Li exceeded them with the serenely misplaced confidence that political impunity was the same thing as personal invulnerability. There is a lesson here that Li’s counterparts in our own system ignore at their peril.

Dum spiro, pugno!

Content retrieved from: http://freedominourtime.blogspot.com/2010/01/killing-commissar-limits-of-submission.html.