Opening the Gates of the Gulag (Pt. III): One Little Victory

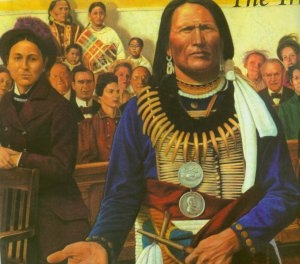

“I am a man”: Chief Standing Bear of the Poncas seeks vindication of his rights in an Omaha courtroom; behind and to his right is his niece and translator, Susette “Bright Eyes” LaFlesche.

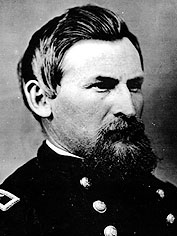

Among those who served in the U.S. Army during the decades-long war to subdue the Indians, few comported themselves more honorably than George S. Crook.

Granted, he didn’t face much competition for that distinction, since there was nothing honorable in the dispossession, often through wanton slaughter, of entire communities in the service of simple greed. Crook, like Kit Carson, was a decent man caught up in a monumental indecency. (Also like Carson, his preferred mount was a mule, rather than a horse.) Having bled and bloodied others on the battlefield, both in the War Between the States and in the campaign against the Sioux, Crook was adamant that – to the extent he had anything to say about it – the Government honor its promises to the Indians.

“He never lied to us,” said Chief Red Cloud of Crook. “His words gave us hope.”

As a government employee who kept his word, Crook was an anomaly, even in his era.

A man of honor: General George S. Crook

Most of those who managed the Federal Government’s Indian policies had no scruples about lying. Among the lies they told were those written in an 1825 treaty with the Ponca Indians, whose Nebraska homeland was a fertile delta between the Niobrara and Missouri rivers.

In exchange for acknowledging the “supremacy” of the Government in Washington, and its territorial jurisdiction over their homeland, the Poncas were promised that Washington would “receive [them]… into their friendship and under their protection, and … extend to them from time to time such benefits and acts of kindness as may be convenient and seem just and proper to the President of the United States.”

Anyone who reads that provision as all such promises issued by the Government should be read – namely, in terms of what it permits the Government to do to you, rather than for you – will understand that it was designed to nullify the rights of the Poncas: It referred to “benefits” and “acts of kindness” to be extended as deemed “convenient” by the Chief Executive, rather than “rights” the Government would be required to recognize and protect.

The lives, liberty, and property of all Poncas, therefore, were contingent on the gracious indulgence of the president. He had complete discretion over how the Poncas were to be treated, and could dispose of them in any way he deemed convenient.

Accordingly, when Anglo-American settlers, drawn westward by the irresistible tug of gold, began to plant homesteads on the Poncas’ homeland in the late 1850s, nothing was done to enforce the Indians’ rights, as they had none – and President James Buchanan, as historian John Upton Terrell puts it, “apparently found it inconvenient to extend any benefits or perform any acts of kindness” on behalf of the Poncas.

In 1858, another treaty was signed between the Poncas and Washington. This was done, in the words of an Indian Bureau report, “for the purpose of extinguishing their title to all the lands occupied and claimed by them, except small portions on which to colonize and domesticate them. This proceeding was deemed necessary in order to obtain such control over the Indians as to prevent their interference with out settlements, which are rapidly extending in that direction.”

The Senate didn’t bother to ratify that treaty for a year. Ingenuously believing that they were dealing with honorable men – neither term applied, of course – the Poncas resettled in their tiny new “homeland,” where they were left without crops or game. By the time the Senate ratified the treaty, hunger and sickness had already taken a terrible toll. Ratification did little to mitigate the Poncas’ plight, since Washington – now in possession of nearly everything it had coveted – had no reason to provide the promised monetary and material support, at least in a timely fashion.

For more than a decade, the Poncas eked out a marginal living. Many of them learned English; more than a few – including Chief Standing Bear, the most respected of the several Ponca Chiefs – became earnest Christians. They were making decent progress when, once again, the political class decided to alter the bargain that had been struck with the Poncas.

In 1876 a despicable little “man” named James Lawrence materialized on the Ponca Reservation. Describing himself as an emissary from the President, Lawrence informed the Poncas that they were to sell their land and relocate to “Indian Territory” — a blighted stretch of Oklahoma that was a 19th-century Siberia for many Indian tribes.

The Poncas quite sensibly withheld their consent until they had seen the land, and spoken with the President. Lawrence was willing to promise the ten Ponca chiefs anything – promises, to creatures of his sort, are just verbal flatulence – in order to get them away from the land and down to Oklahoma.

Once the chiefs were in Oklahoma, Lawrence told them that there would be no payment for the Poncas’ land in Nebraska, and that they had no choice but to re-settle in Indian Country on three infertile plots of land.

“If you do not accept these [plots of land], I will leave you here alone,” Lawrence told the chiefs. “You are one thousand miles from home. You have no money. You have no interpreter, and you cannot speak the language.”

Lawrence left the chiefs without so much as a safe-conduct pass.

The following morning, after Lawrence had left for Washington, the Ponca chiefs set out, on foot, in the dead of winter, for home. Fifty days later they arrived at the Reservation of the friendly Otoe Indians. On their arrival, the Indian Agent told them he had received an official telegram alerting him that the Ponca chiefs were to be considered renegades, and that they should receive no food, shelter, or assistance of any kind.

This particular Agent was several cuts above the degenerates who generally filled such posts. He asked the Ponca chiefs to tell their side of the story, which they did. He permitted them to stay for ten days, allowing them to rest and eat and otherwise recruit the necessary strength to finish their trek. He later recalled that when Standing Bear and the other nine chiefs fist entered his office, they left bloody footprints on his floor.

A week after they left, the Poncas arrived at the Omaha Reservation. They dispatched a telegram to Washington, seeking to inform the President of what had happened to them. Receiving no reply, they headed home. Four days later they arrived, to find Lawrence there waiting with a detachment of troops.

“Tomorrow, you must be ready to move,” the hell-bound (and now hell-dwelling) Lawrence told the Poncas. “If you are not ready you will be shot.”

Even in their emaciated and weary condition, the Ten Ponca Chiefs were willing to resist Lawrence.

“This land is ours,” Standing Bear and his associates informed him. “It belongs to us. You have no right to take it from us. The land is crowded with people, and only this is left to us. Let us alone. Go away from us.”

Lawrence sent for reinforcements, and a few days later the Poncas were evicted from what remained of their homeland at bayonet point. Their homes, barns, school and church were destroyed. The entire community — several hundred people — was driven like cattle down to Oklahoma.

(Thanks to Scott Horton)

“Many died on the road,” Standing Bear later recalled. “Two of my children died. The winter was very bad. All our cattle died; not one was left.” The three-month forced migration became a death march, claiming 158 Poncas, most of them elderly and children.

At every stop along the trail, settlers – most of them organized by local churches – went out to minister to the Poncas, offering what they had by way of food, blankets, and other necessities. Similar acts of charity had been offered to the “renegade” Ponca chiefs during their trip from Oklahoma.

These defiant acts of Christian decency rank very high on the list of reasons why I’m proud to be an American.

Shortly after the Poncas arrived at their new “home,” Chief Standing Bear’s only son took seriously ill. The youngster – whose most precious possession was a Bible – knew he was going to die. Shortly before he expired, he asked his father to take his body back to the Ponca homeland on the Niobrara, where it could await the resurrection near the mortal remains of his family. Standing Bear made that promise – and kept it.

In the company of thirty others, Standing Bear began the long walk back to the Niobrara. Once again he was designated a “renegade,” and orders were cut in Washington to arrest him and his party. On arriving in Omaha, Standing Bear was given a small plot of land to grow wheat, which his tiny band desperately needed. He was working in the fields when soldiers arrived to arrest him for deportation back to Indian Country.

Fortunately, in 1878, there was something akin to a free – which is necessarily to say anti-government – press in this country. The editor of the Omaha World-Herald, a one-time circuit-riding preacher named Thomas Tibbles,* wrote a detailed and passionate story describing the manifold injustices suffered by Standing Bear and his people. Conveyed by the telegraph wire (the 19th century equivalent of the Internet), Tibbles’ account was widely republished, and a healthy outrage seized the public.

To the immense good fortune of Standing Bear, General George S. Crook was dispatched to Omaha to take the Poncas into custody and take them back to Oklahoma.

Crook had no appetite for the assignment, and wasn’t in a hurry to carry it out. So Crook permitted the Poncas a decent interval to rest. In the meantime, the General put his time to good use, first by indulging in his favorite hobby, weightlifting, and secondly by getting a detailed briefing on the case from Thomas Tibbles.

At some point, according to Stephen Dano-Collins’ wonderful book Standing Bear is a Person, Crook agreed to be party to a lawsuit involving Standing Bear. Crook, it should be noted, agreed to be the defendant in the suit, which was filed under the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Standing Bear’s attorneys, John Webster and A.J. Poppleton, also filed a habeas corpus motion in order to bring the chief, who was in military custody, before a judge.

Here’s where things take a familiar turn.

The attorney representing the criminal syndicate called the federal government, G.M. Lambertson, insisted to Judge Elmer Dundy that neither the Fourteenth Amendment, nor the habeas corpus guarantee, applied to Standing Bear, or to any other Indian, because they were not “persons” for the purposes of the law.

Judge Dundy, like several other individuals involved in this affair, was an exceptional man. He granted the habeas corpus motion filed on behalf of this “non-person” — a renegade Indian, which is to say an “unlawful enemy combatant” — and permitted the trial to proceed. Standing Bear followed the courtroom proceedings with the translation help of his niece Bright Eyes, also named Susette LaFlesche, a schoolteacher who would go on to marry Thomas Tibbles.

At the end of the trial, Judge Dundy permitted Standing Bear to address the court.

Clad in the quiet dignity that had never deserted him, Standing Bear arose and, for nearly an entire minute, held out his hand for the judge and gallery to see.

“That hand is not the color of yours, but if I pierce it, I shall feel pain,” the chief told his audience, who sat in chastened silence. “If you pierce your hand, you also feel pain. The blood that will flow from mine will be the same color as yours. I am a man. The same God made us both.”

Nothing was said by anyone for several long, airless moments after Standing Bear resumed his seat. Tears were cascading from the eyes of many witnesses, male and female alike. General Crook’s eyes, which had seen spectacles of blood and horror most people couldn’t imagine, were shielded by one of his large, callused hands as he averted his face from the crowd.

Judge Dundy ruled in favor of Standing Bear. Which is to say that the judge ratified the obvious facts of nature: As a human being made in God’s image, Standing Bear was a person, even though the positivist “law” insisted that he was not. As a person, he was entitled to the protection of the law, including the habeas corpus guarantee and the immunities recognized by the Due Process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Yes, that Amendment was never properly ratified, and yes, it has been the instrument of incalculable mayhem. Its application in the case of Standing Bear is the only instance of which I’m aware in which it was used correctly – to beat back the tyrannical impulses of the central government.

Of course, Leviathan – even in the relatively immature stage of growth it had reached by April 1879, when Judge Dundy issued his ruling – wasn’t about to concede. An appeal was immediately filed; bills to circumvent the decision were drafted in Congress; the government-aligned press blackened editorial pages with dire warnings about the tumult and terror that would ensue if every Indian consigned to a reservation suddenly discovered he had standing in civilian courts, and the legal means to challenge his detention.

The contemporary parallels are so patent and plentiful I feel embarrassed even to draw specific attention to the fact.

Knowing that money would have to be raised to continue the legal struggle, and that Chief Standing Bear was the best advocate for the cause, Tibbles went on a fund-raising and speaking trip along the eastern seaboard with the Chief and Bright Eyes. They were in Boston on October 31 of 1879 when they were informed that Chief Big Snake, Standing Bear’s brother, had been murdered by federal thugs in Oklahoma.

Eventually, with the help of General Crook (who – in addition to arranging Geronimo’s March 1886 surrender in Sonora, Mexico’s Canon de los Embudos – became a passionate advocate for Indian rights), the Poncas were permitted to resettle in their Nebraska homeland. But this outcome was very much the exception.

The rule was better defined by the December 29, 1890 U.S. Army massacre of up to 300 Lakota Sioux at Wounded Knee, which was the last and defining atrocity of the federal Indian War. Between 20 and 30 soldiers were awarded the Medal of Honor for their involvement in America’s Babi Yar, which – as Major S. Leon Felkins, U.S. Army (ret.) points out, followed the familiar morphology of genocide. The Sioux were disarmed, deprived of legal status as individual persons, physically concentrated under military rule, and then demonized in the public mind as a deranged, terroristic menace to the public.

One of these images depicts Wounded Knee, South Dakota, December 1890; the other, Babi Yar, Ukraine, September 1941. Can you tell which one is which?

Again, it would seem gratuitous to elaborate on the relevant parallels and continuities between that episode of our national history and the one we see unspooling before our eyes.

Suffice it to say, once again, that when the Government that rules us asserts that individuals or groups living under its jurisdiction can be designated non-persons for the purposes of law by the president, and detained for such time, and in such way, as meets with presidential approval, it is laying the foundation for a gulag. We’ve been there; we’ve done that. We must not let it happen again.

*Tibbles, candor compels me to acknowledge, was not altogether commendable. As a young man with a taste for violent idealism, he rode briefly with the Ayatollah John Brown, but apparently wasn’t involved in any of Brown’s most repellent acts. Every man is entitled to a Persian flaw, I suppose, and this youthful indiscretion could be considered the Trouble with Tibbles, as it were.

Oh, and while we’re on the subject of self-indulgent allusions, the subtitle of today’s installment does indeed refer to this. (Sorry the sound is so poor.)

Content retrieved from: http://freedominourtime.blogspot.com/2006/11/opening-gates-of-gulag-pt-iii-one.html.