Thursday, March 19, 2009

Remembrance of Recessions Past

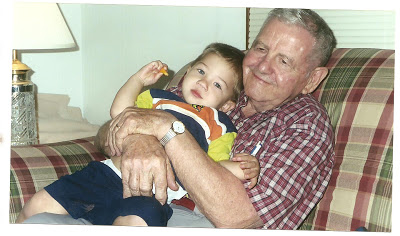

The greatest man I will ever know: My father, L. Richard Grigg, holding his grandson, Jefferson Leonidas Grigg (age 3 at the time), circa 2004.

At some point in each visit we pay to my parents’ home I find myself pondering a curious object found in their washroom — a small glass cologne dispenser in the shape of a mallard.

The artifact entered my childhood home as a Nixon-era Christmas present to my father, and has survived no fewer than a dozen migrations across three states. The aromatic toiletry dispensed from it has a pleasant if generic scent vaguely reminiscent of Hai Karate (a 1960s-era cheapie cologne that was marketed as an Axe-style olfactory aphrodisiac.). To this day the decanter appears to be a little less than half full.

The sight of that insipid little cologne bottle has an effect on me akin to that described by the protagonist from Remembrance of Things Past as he consumes his first morsel of tea-soaked Madeleine cake. I find myself irresistibly transported back to my childhood in a home presided over by loving, thrifty parents whose formative years were indelibly marked by the experiences of the (last) Great Depression.

Like tens of millions of Americans, my mother and father lived by the Depression-era credo, “Use it up, wear it out; make it do, or do without.” They would never buy something new — an appliance, an article of clothing, an automobile, or a piece of farm equipment — when it was possible to extend the lifespan of a suitable item already in our possession.

My parents, like many others of their generation, preferred saving to spending, and self-reliant home production to the typical consumer lifestyle.

We always had a garden, albeit sometimes a very small one, in order to grow our own produce, which was always much better than what we could buy at a grocery store. Mother always canned whatever we harvested; she also baked bread (often from grain we grew ourselves), churned butter (from a cow I often milked by hand), and kept our old clothes in good repair. Dad would only throw something away if he couldn’t devise some suitable use for it, and in doing so he constantly surprised me by the depth and variety of his imagination.

During the early 1970s, after Nixon definitively de-coupled the dollar from gold and our economy was plunged into a recession, Mom and Dad began to stock up on survival foods of various kinds.

In keeping with the prime directive of food storage — “store what you eat, and eat what you store” — our family soon became acquainted with the odd but hardly unpleasant flavor of storable surrogates for more familiar staples, such as carob powder as a replacement for cocoa, and textured vegetable protein (TVP) as a substitute for sausage on pizza.

In 1979, as Carter-era stagflation plagued the national economy, our family relocated from eastern Oregon to southwestern Idaho. Shortly before our move, my father — a real estate broker — consummated a sale in which the closing costs were paid, in part, by a large quantity of silver in the form of bars as large as 100 ounces.

After we re-settled in Madison County, Dad put the silver in safe storage and tried to establish himself in the local real estate market.

Unfortunately, we arrived just as a reconstruction “boom” went bust.

In June 1976, Idaho’s Teton Dam failed, resulting in a flood of nearly Katrina-esque proportions.

The Teton Dam was little more than a very large berm, constructed with government-standard indifference according to familiar government-standard practices — in other words, through the exercise of minimal competence at maximum expense.

(Ironically, one eyewitness to the disaster was a farmer named Daryl Wayne Grigg, who is — as far as I can tell — no relation.)

The Feds spent $100 million to build the Teton Dam; it spent at least $300 million in settling damage claims. For more than two years, federal money poured into communities throughout the devastated floodplain, including Madison County. But the reconstruction boom was over by the time our family arrived, and the real estate market collapsed like a traumatized souffle, or better yet, like a federally constructed dam.

Glory Days: Your author, as he appeared during the last major recession, roughly three decades and sixty pounds ago.

For the five years spanning most of my time in high school and college — 1979-1984 — my Dad’s real estate business, in practical terms, produced no income.

Facing a moribund real estate market, my Dad opened another revenue stream: He and two of my brothers, along with a rotating cast of neighbors, opened a bicycle repair shop. This was a business suited to recessionary times, in which people, once again, seek to extract as much use out of what they have.

The bike repair business brought in a modest but indispensable stream of income. But what saved our family from utter destitution was Dad’s silver hoard.

In January 1980, about a year after our family moved to Rexburg, Idaho, silver peaked at a little more than $50 an ounce. Dad sold his entire hoard, which had appreciated by several hundred percent over its original market value, just off the peak price. That transaction provided our family with sufficient funds to survive for more than a year.

Shortly thereafter, our family became involved in a short-lived but very worthwhile alternative local economy built on the barter system.

Consumer items of various kinds — clothing, jewelry, household goods, storable foods — were pooled and then assigned credit value according to market demand; those “credits” were then withdrawn and used to purchase whatever their owner desired. It was in this way that my three younger brothers and I were provided with school clothes in the fall of 1980, and presents the following Christmas. Alas, that worthy enterprise perished after the parasitical clique calling itself the government contrived a way to tax it.

During this period I was a teenager largely oblivious to the stressful challenges confronted by my parents as they tried to provide for a family of nine with no conventional means of earning a living.

My biggest preoccupations at the time involved such things as learning the guitar stylings of Michael Schenker and Frank Marino, keeping up with my self-imposed nightly football workouts (which at the time consisted of 1,200 situps and about half as many pushups), and wondering if I’d ever run into an Erin Gray lookalike.*

I had only the sketchiest idea of the genuinely heroic efforts being made by my parents not only to keep our family alive, but to make their large brood of omnivorous children happy.

Owing entirely to the thrift and industry of my parents, our family survived a severe national recession and a local depression without suffering noticeable privations of any kind. We were well-clothed, well-fed, blessed with a comfortable home and surrounded by a surprising number of amenities.

Several times since then my parents have suffered severe reversals of fortune. At one point they were forced to live without reported income in the late 1980s owing to the efforts of a corrupt tax collector (but then I repeat myself) to extort personal payoffs from them. (My father adamantly refused to reveal his identity to me at the time he was making life miserable for him and my mother. “Dad, tell me who it is,” I demanded. “Why do you want to know?” he asked. “It’s better that I not answer that question,” I replied. “Well, then, I can’t tell you,” he said, ending the conversation.)

Our family was immensely blessed by the Depression-era lessons learned by my parents regarding self-discipline and deferral of gratification. It’s hardly surprising that people who displayed such commendable austerity would keep a bottle of cheap but serviceable cologne for nearly four decades; after all, it hasn’t been used up, so why throw it out?

Obviously, my parents fit the profile of “hoarders” — people who shirk the patriotic duty to spend everything they make, leverage themselves as deeply as they can, and consume as much as possible in order to boost “aggregate demand.”

In fact, people of that insular, provincial mind-set are responsible for the ongoing economic collapse, according to the bien-pensants.

The stolid refusal of hoarders to do their part is undermining the generosity of the Federal Reserve in pumping “liquidity” (that is, inflated dollars) into the economy, and the heroic efforts of Obama the Good and Wise to spend as much as possible to restore prosperity to our troubled land.

In a cover story lamenting the fact that the past year and a half has witnessed a cultural shift from profligacy to parsimony, Newsweek strikes a tone at once patronizing and accusatory in addressing those who choose to save rather than spend.

“The rush to hoard cash and pinch pennies is understandable, given that some $13 trillion in net worth evaporated between mid-2007 and the end of 2008,” the story begins, and if it had been written by an honest and rational man the matter would have ended there. But the author perversely persisted, ignoring sound economic sense in favor of forcing a Keynesian homily on his long-suffering readers.

While it “makes complete microeconomic sense for families and individual businesses” to economize, that behavior “is macroeconomically troubling,” Newsweek continues. “For our $14 trillion economy to recover and thrive, hoarders must open their wallets and become consumers…. [I]n our economy in which 70 percent of activity is derived from consumers, we do need our neighbors to spend. Otherwise we fall into what economist John Maynard Keynes called the `paradox of thrift.’ If everyone saves during a slack period, economic activity will decrease, thus making everyone poorer.”

The same rebuke is offered, in much sterner language, by the New York Times. In the midst of a paean to the Federal Reserve for conjuring into existence more than $1 trillion to buy bad debts — hundreds of billions in worthless mortgages from Fannie and Freddie, and even more to purchase Treasury bonds — the Times takes a swipe at “lenders [who are] unwilling to lend and borrowers [who are] unwilling or unable to borrow.”

According to Jay Hatzius, chief economist at Goldman Sachs (aka the Shadow Treasury Department), our deepening economic collapse is entirely the fault of those narrow-minded “hoarders”: “We’re in a deep recession mainly because the private sector, for a variety of reasons, has decided to save a lot more.”(Emphasis added.)

Now, Hatzius works for Goldman Sachs, which means that he’s a bit like a mob bookkeeper, albeit much less reputable and trustworthy. Minds not terminally clotted by Keynesianism should be able to understand that Hatzius is deliberately confusing cause and effect, and maliciously blaming the victims in order to exculpate one the chief offenders in the recently ended orgy of Fed-abetted financial fraud.

The Times, a dying propaganda appendage of the Power Elite (and may its demise come quickly), would have us believe that the key to prosperity is the Fed’s ability to create “vast new sums of money out of thin air” — the exact phrase it used to describe the recent “injection” of $ 1 trillion by the central bank into the U.S. economy — coupled with unbridled consumption by both government and the population at large.

Sounder minds understand that there is no discontinuity in the economic laws governing both “micro”- and “macro”-economies: Neither nations nor households can build prosperity through debt and consumption, but rather through thrift and productivity.

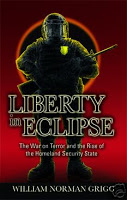

The emerging media campaign against “hoarding” has a nasty and unmistakable flavor of Stalin-variety collectivist scapegoating: The term “hoarders” was produced by the same propaganda mill that churned out official imprecations against “wreckers” and “kulaks.”

Whenever a collectivist regime expands its control over an economy, it has to find somebody to blame for the inevitable dislocations, shortages, and hardships.

Typically such ruling elites re-direct blame at those who behave in rational economic behavior. And scapegoating in such circumstances is inevitably a prelude to outright confiscation of wealth, and, eventually, the liquidation of those intransigently committed to individual freedom and dignity.

The Fed and its cohorts are already confiscating the earnings of “hoarders” through inflation. But as the effects of Obamanomics become tangible, and our country begins to follow the course charted by Zimbabwe, those responsible for the disaster won’t be content with such an indirect assault.

Already we’re being told that it’s un-American to divest ourselves of fiat dollars in favor of gold and silver. Obama the Blessed Himself has ordered Americans to refrain from stashing their money under their mattresses. And there’s even an intriguing effort underway to categorize the “hoarding” tendency as a variety of obsessive-compulsive behavior; this offers intriguing and terrifying possibilities for Soviet-style compelled psychiatric imprisonment for those who prefer to wear out what they have, and save their money rather than spending it.

Ours is hardly the first society to succumb to the plague of fiat money and inflation, and the totalitarian regime being fastened upon us will hardly be the first to anathematize and, perhaps, seek to annihilate, those who insist on protecting what they’ve earned and saved.

Be that as it may, our only plausible hope for survival — as individuals and families, and as voluntary communities of shared interests and values — is to do exactly the opposite of what the government instructs us. And this begins with the careful study, and appropriate emulation, of the wise people who are increasingly maligned as “hoarders.”

__

*Miss Gray, for the uninitiated, played the redoubtable Col. Wilma Deering on the late-70s fromage-fest Buck Rogers in the 25th Century. She is a lovely and, by all accounts, very decent lady, but in terms of radiant beauty, comparing her to my Korrin is a bit like comparing a penlight to a supernova.

Dum spiro, pugno!

Content retrieved from: http://freedominourtime.blogspot.com/2009/03/remembrance-of-recessions-past.html.