September 11, 1857

“You guys do know what that movie is about, don’t you?” inquired the friendly young lady in the admissions booth as Korrin and I bought tickets to see September Dawn.

“You guys do know what that movie is about, don’t you?” inquired the friendly young lady in the admissions booth as Korrin and I bought tickets to see September Dawn.

“Yes, of course,” I replied, a twinge of puzzlement creasing my care-worn brow. “Are you required to offer a disclaimer of some sort for some reason?”

“No,” she answered. “It’s just that some people have been offended by the subject matter.”

As we entered the theater in Nampa, I commented to Korrin that it seemed oddly fastidious of the management to express concerns about the content of that particular film, when elsewhere in the multiplex patrons — by their own informed choice, one assumes — were enduring an onslaught of adolescent sex humor (Superbad), reveling in hyper-violent revenge fantasies (War), or otherwise spending a couple of hours immersed in Hollywood-issue degeneracy.

I suspect that the reason September Dawn was singled out in this fashion was because it has been quietly but effectively branded an offense against “tolerance.”

This is unfortunate: Of the films presently on offer, September Dawn is the only one representing a serious and commendable attempt to dramatize actual history — in this case, the systematic, premeditated murder in southern Utah of 120 members of a California-bound wagon train.

The definitive (thus far) treatment of the Mountain Meadows Massacre is Will Bagley’s award-winning book Blood of the Prophets. The following clip offers a concise summary of the episode:

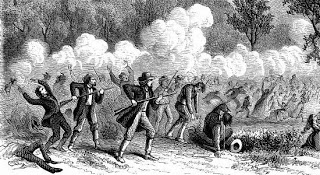

The victims were Arkansans led by Alexander Fancher, whose Hugenot ancestors had fled France following the St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre. The perpetrators were militiamen and Paiute Indians whose efforts were organized and directed by local Mormon leaders. The atrocity was a calculated act of terrorism carried out in the context of the Mormon leadership’s asymmetrical war with the federal government, which was becoming acute at the time the ill-fated wagon train arrived in Utah: President James Buchanan, believing (with some reason) that Mormon Prophet and territorial governor Brigham Young was bent on establishing a hostile theocracy, had dispatched a military force (“Johnson’s Army”) to remove Young and install a territorial government more to Washington’s liking.

Critics have ruthlessly panned the film, many of them complaining that its depiction of fanatical Mormon murders and winsome Protestant victims is childishly one-sided. This criticism is sound, and the film — as a work of entertainment — would have benefited greatly had the director not been a stranger to subtlety.

But the problem here is with the story itself, which isn’t fraught with ambiguities and complexities. The matter really was quite simple: Mormon priesthood leaders (the church has a lay priesthood), acting on oaths to avenge the deaths of Joseph and Hyrum Smith and in accordance with the doctrine of “blood atonement,” conspired to annihilate an entire wagon train of innocent, inoffensive people. They did so in the belief that they were doing God’s will, and that the killings had been ordered by their religious leaders, who were for all intents and purposes infallible.

In recent months, the Mormon leadership has finally admitted that local church leaders were involved in the massacre; this concession comes after 150 years of stolid stonewalling on the subject, beginning with Brigham Young’s cover-up campaign in which he acted as an accessory after the fact to mass murder. Roughly two decades after the event, John D. Lee, an adopted son of Brigham Young who had a hands-on role in the killing was the only one to be convicted and executed for the crime.

Bagley contends — convincingly, in my view — that the crime itself was ordered by Brigham Young. September Dawn embraces that perspective, and in one of the few instances the film embraces nuance, the order from Brigham is portrayed more along the lines of “Who will rid me of this meddlesome priest?” rather than as a blunt directive from a standard-issue cinematic villain.

Given the vilification of the Arkansans in Mormon folk mythology, there is some irony in current protests from Mormon media figures that September Dawn demonizes the Mormon assailants and beatifies the victims.

Folk accounts of the wagon train depict it as a cross between a pack of Hell’s Angels in Conestoga Wagons and a traveling brothel: The women were slatternly, the men uniformly violent and abusive, the children little more than curs. Included in the company (once again, according to myth) were Missourians who had helped drive out the Mormons during the so-called Mormon War of 1838 — and one of them boasted of having the very gun that killed Joseph Smith. By this account, the wagon train arrived in Utah and immediately began heaping abuse on the Mormon settlers and poisoning livestock in order to rile up the Indians.

To their credit, contemporary Mormon historians reject this depiction of the victims, even though they still try to compartmentalize blame for the massacre by laying it exclusively at the feet of local Mormon leaders. As September Dawn tells it, Brigham was “in the loop,” but left it to his followers to handle the details. This strikes me as a very plausible depiction.

Writer-Director Jonathan Cain does a suitable job establishing his setting, in which he presents a personalized drama involving four key fictional characters: Bishop John Samuelson (Jon Voight), his sons Jonathan (Trent Ford) and Micah (Taylor Handley), and Emily Hudson (Tamara Hope), an Arkansan who falls in love with Jonathan.

Bishop Samuelson is a polygamous husband to eighteen women. His younger son Micah has already started a seraglio of his own, but Jonathan — who believes that marriage should be the product of genuine love, not dutiful compliance to doctrine — has no interest in marrying anyone, at least until he sees Emily. Tasked by his father to spy on the emigrants, Jonathan finds himself spending time with Emily, with predictable results: They quickly fall in love, despite the cultural chasm separating them.

Emily is a Pastor’s daughter, which puts her in a position analogous to Jonathan. They have a brief but illuminating conversation in which the stark differences between their faiths are quickly sketched out: To Jonathan, the emigrants, like all non-Mormons, are “gentiles,” and it puzzles him that Emily’s father doesn’t seek to control those under his pastoral care. Emily, apparently believing Mormonism to be simply another variant of conventional Christianity, is just as puzzled by Jonathan’s casual acceptance of authoritarian notions and his unfamiliarity with the Beatitudes.

This scene, although somewhat overbroad and anachronistic in tone (Emily sounds a bit too much like a 21st Century Megachurch Evangelical, rather than a mid-19th century Protestant pioneer), does offer a useful illustration of the distance that separates Mormonism from mainline Christianity in terms of doctrine and practice. This is particularly true of the high-octane, theocratic version of Mormonism taught and lived in Brigham’s Caliphate.

When in the film Jonathan casually tells Emily that his father considers the beliefs of the emigrants to be “abominations,” the character is accurately giving voice to the Mormon perspective on mainline Christianity. When the film’s version of Brigham Young (Terrance Stamp, whose experience in playing the Kryptonian megalomaniac Zod offered valuable training for this role) speaks of blood atonement — shedding the blood of those whose sins supposedly aren’t covered by the blood of Christ, so as to give them an opportunity for exaltation among the “Gods” — his dialogue is taken directly from documented sermons and writings.

And when Bishop Samuelson insists that his Mormon priesthood leaders are immune to error, he is preaching sound and unassailable doctrine — from the Mormon perspective, then and now.

The atrocity at Mountain Meadows was the predictable product of a familiar set of ingredients: A power-obsessed, authoritarian leadership that cultivated a siege mentality among its followers; a murderously perverted form of altruism in which lethal violence directed at the targeted victims was depicted as a form of compassion (it would expunge their sins, after all, and give them a chance for salvation); and a doctrine of obedience that relieved followers of moral responsibility for carrying out the orders of their leaders.

Every time, and any time, those ingredients are combined, people will die in large numbers. This was true of the wars of revolution and empire following the Jacobin revolution in France; it was emphatically true of the quasi-genocidal campaign to “civilize” the American Indians (somebody really should make a film about the Sand Creek Massacre); and it was true at Mountain Meadows.

But it is also true of the ongoing war in Iraq, as well. There is no moral or material difference between Brigham Young infecting his followers with war fever and then turning them loose on helpless Arkansans, on the one hand, and the cynical exploitation of terrorism by Bush and Cheney to manipulate our nation into invading Iraq, on the other.

After all, we’re told, the president knows so much more than we do, and those who carry out his orders — whether to destroy a city or sexually torture a child — partake of the president’s moral immunity. And the Iraqis should be grateful to us for the humanitarian violence we’ve inflicted on them: Don’t they know this is their only chance to embrace the gospel of democracy?

Double Video Bonus

Gratuitous as it might seem, I’m offering clips of two incendiary performances by the incomparable Thin Lizzy. The songs selected are on-topic: They deal with the bloody consequences of fanatical self-righteousness.

“Massacre”

“If God is in heaven, how can this happen here? In God’s name they used weapons for the massacre….”

“Holy War”

“We are chosen; we are one; we are frightened of no one … and no one will win this war — this is the way, this is the law.”

Please be sure to check out The Right Source and the Liberty Minute archive.

Content retrieved from: http://freedominourtime.blogspot.com/2007/08/briefly-considered-september-11-1857.html.