The Real Drug War Kingpins

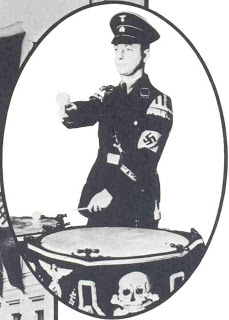

Not a scene from a movie, or from the streets of Baghdad: “Police” — that is, Pentagon-equipped and federally-funded occupation troops — conduct a raid in Detroit.

Mike Nifong’s career as the Torquemada of Raleigh, North Carolina is over, although the self-enraptured prosecutor couldn’t resist one final lachrymose moment in the spotlight. But Nifong the Good – also known as Nifong the Wise, and Nifong the Misunderstood – deserves some company. He shouldn’t be allowed to Bogart that pity pipe.

There are plenty of other corrupt and abusive prosecutors – US Attorneys, State Attorneys General, District Attorneys, and the like — who deserve to be bathed in the same disrepute, and subject to the same professional ruin, that Nifong must now endure. Andrew Payton Thomas of Phoenix is one. Georgia Attorney General Thurbert Baker, who insists on prolonging the utterly insane imprisonment of Genarlow Wilson, is another.

But today let’s focus on the case of John Paschall, one unfathomably vicious little distaff canine.

Paschall is District Attorney for Robertson County in Texas, in which capacity he has long been the local Narcotics Kingpin.

No, he doesn’t synthesize, sell, or consume the contraband, at least as far as is publicly known.

Paschall is not in charge of drug manufacturing or distribution, but rather what could be called the “fulfillment” department: He heads up the local counter-narcotics task force, which – until quite recently – conducted an annual raid on the local black population in order to produce arrests in sufficient abundance to keep federal Byrne Grant money flowing.

A class-action suit (.pdf) filed against Paschall and the Task Force by the ACLU (insert standard disclaimer here) plausibly alleged that the DA and his associates “have for many years recruited confidential informants, facing criminal charges, by threatening them with extraordinarily lengthy prison terms unless they will implicate numerous named African-American residents in drug sales…. [T]he informant is required to fill a large quota or else he faces lengthy imprisonment.”

Starting in the mid-1980s, the Task Force would conduct an annual raid in Hearne, a Texas town of about 5,000 people. Paschall, according to witness accounts cited in the lawsuit, “publicly and openly joked about the sweeps, saying that it was `time to round up the n*****s,’ and laughed about watching African-American residents run in fear during the sweeps. Paschall described the fleeing residents as cockroaches.”

Some of the raids would focus on a housing complex called Columbus Village, a federally subsidized complex housing many black residents. Paschall reportedly expressed the opinion that it would be better for the community if Columbus Village residents “were removed from Hearne by incarceration or other means,” specifically suggesting that the project should be “bombed” and “burned.” But this wouldn’t be as profitable as drawing up rosters of Columbus Village residents to be hauled in during the annual paramilitary sweep, so Paschall didn’t pull the trigger on his “Destroy Columbus Village to save the town” strategy.

In late 1999, Paschall hauled in a recently paroled petty criminal – a small-time thief with a recurring drug addiction named Derrick Megress — and blackmailed him into acting as a confidential informant. Paschall had a long history with Megress, and in the following detail of that history we see the unique viciousness that distinguishes Paschall even in the detestable company of Nifong, Thomas, and Baker, the abusive prosecutors mentioned above.

As a juvenile, Megress was hospitalized for serious mental illness, a fact well known to Paschall, who was the one who had the youngster committed. Paschall exploited that vulnerability when the time came to recruit him as an informant, making use of his victim’s fears and anxieties: The prosecutor threatened to send Megress to prison for “60 to 99 years,” and to prosecute members of his family who were innocent of any wrongdoing, if the young parolee didn’t cooperate. While Megress was incarcerated, some Task Force members allegedly provided additional inducements by beating him regularly and threatening his life.

Megress was specifically required to implicate at least twenty suspects, and would receive a $100 cash payment for each additional name. He was given a tape recorder to document his alleged purchases. He eventually implicated 27 local residents, almost all of whom knew him, and all but one of whom were black. But the only “evidence” offered “that Megress purchased drugs from anyone … was his own self-serving word,” contends the lawsuit.

In late October and early November, the “sweep” took place as planned, and police detained nearly the entire black population of Hearne. One young man with Down’s Syndrome was thrown “onto the ground, handcuffed, and forced … to lie immobile. They never asked him for his name or identification during his entire detention.” Clifford Runoalds was arrested while on his way to the funeral of his 18-month-old daughter.

Many were arrested and charged with drug dealing despite their ability to provide airtight alibis corroborated with time cards and even security camera footage proving they were at work at the time of the supposed deals.

When the police showed up at the Chelsea Street Pub and Grill in pursuit of Regina Kelly, the young single mother assumed that she was in trouble because of unpaid parking tickets. She went along peacefully, only to learn to her horror that she was accused of narcotics trafficking. She spent two nights in jail, wearing her waitress uniform, on a $70,000 bond. Regina would eventually spend almost a month in jail before the bail was reduced to a sum her mother could afford (she mortgaged her land to pay $1,000 bond).

The indictment “listed Kelly’s first name as Jennifer,” notes an account in the Village Voice. That alone should have been sufficient reason to dismiss the case. In addition, “The secret audiotape allegedly incriminating her did not have a single female voice on it. Her prosecution rested on the uncorroborated word of Derrick Megress….”

With no money, no help from distracted court-appointed defenders, and nobody at home to care for her children, Regina’s cellmate, another single mother named Erma Faye Stewart, took a deal, pleading guilty to distributing narcotics in a drug-free zone. She received 10 years’ probation and was required to pay $1,800 in fines. “Those who refused to take a plea and couldn’t post bond, spent five months in prison awaiting trial,” observes a Frontline documentary on the case.

Victims of a “war” against victimless “crimes”: Erma Faye Stewat (l.) and Regina Kelly.

About four months after the arrests, the first trial began, and the case disintegrated like cotton candy in an acid bath. Megress was exposed for all to see as a spectacularly worthless witness. So the charges against all of the defendants were dropped – except those who, like Erma Stewart, from whom a plea bargain had been extorted.

Describing Erma’s plight three years ago, Frontline reported:

“Three years after she pleaded guilty in order to go home and take care of her children, she is destitute. Because of the plea, she is not eligible for food stamps for herself or federal grant money for education. She can’t vote until two years after she completes her 10-year probation. And she has been evicted from her public housing for not paying rent. Her children sleep in various homes and she spends her nights outside the housing project, waiting for the morning when she can go to work as a cook – a job that pays $5.25 an hour. She owes a $1,000 fine, court costs and late probation fees which she says she has been pressured to pay. `They see it like, as long as I have a job, I can pay them…. I already told them, I’m having a hard time, buying my son medicine. I have to have his medicine for his asthma. They don’t really care about that. All they want is, you know, the money.’”

That’s what this is all about: The money.

Getting a quota of arrests was necessary in order to qualify for continuing Byrne Grants – which are a form of welfare for local police. This meant treating the local federally subsidized housing project as a hunting ground for the usual suspects, and anybody else who looked like a suitable candidate for arrest. And Paschall and his cronies didn’t scruple to steal the money honestly earned by one of their victims, even if it meant depriving one of her kids of medicine he needed in order to breathe.

After the Frontline special was broadcast, people from across the country donated over $18,000 to Erma. Unfortunately, she found herself in trouble with her probation officer after she tested positive for marijuana and cocaine use; this means she has a weakness, just like anyone who throws back one or a dozen brewskis too many. (If she’s been spending some of her meager earnings on drugs while her asthmatic son goes without medicine, Erma’s got some serious problems that only God can fix.) But she wasn’t convicted of mere possession; she was forced to plead guilty to first-degree felony distribution, a charge for which no evidence was ever produced.

Oh, and Paschall, always the quintessence of class, offered this reaction regarding the humanitarian outpouring toward Erma: “She can get on TV and she can cry all she wants to, but she’s her own worst enemy because she continues using drugs. She’s going to have to get her act clean or suffer the consequences — TV show or not.”

Paschall, of course, is just the person to lecture others about accepting the “consequences” of their actions.

The lawsuit against him was settled in 2005. The terms of that settlement are confidential, but probably fairly lucrative to the ACLU (which does quite well for itself in cases of this sort – another issue I have with the “war on drugs”: It helps subsidize the ACLU, which has never gotten out of the business of brow-beating local communities over traditional religious displays and other cultural conventions the organization doesn’t like).

Of course, before agreeing to a settlement, Paschall filed a motion asserting – I am not making this up – three different kinds of immunity: “prosecutorial immunity,” “qualified immunity,” and “official immunity.” US District Judge Walter S. Smith Jr. rejected all of Paschall’s claims with the same thoughtless ease Tim Duncan would display in stuffing my flat-footed “jump” shot. This no doubt explains Paschall’s eagerness to settle the case.

And yet – there he sits, still clothed in whatever dignity and prestige his office confers upon him, while the victims of his corrupt ambition do what they can to keep body and soul, and families, together.

Video Extra

Regina Kelly recounts her experience to Radley Balko, senior editor for Reason magazine:

Former Texas counter-narcotics police officer Barry Cooper describes how police become addicted to the “war on drugs”; no, seriously:

Please be sure to visit The Right Source.

Content retrieved from: http://freedominourtime.blogspot.com/2007/06/not-scene-from-movie-or-from-streets-of.html.