“These Are MY Sons!”

Charlie Anderson, a widowed father of six sons, was working on his ranch in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley when the Confederate patrol descended on his property. Displaying the reflexive hospitality of a natural gentleman, Charlie happily permitted Lt. Johnson and his soldiers to help themselves to the family well.

Though both his men and their horses were tired and parched, Captain Johnson hadn’t come to the Anderson Ranch simply to relieve their thirst.

“You have six sons, don’t you, Mr. Anderson?” inquired Johnson.

“Well, does the size of my family have some special interest to you?” responded Anderson, his eyes narrowing in suspicious hostility.

“Matter of fact, it does,” replied Johnson, his genial veneer disintegrating. “We need men. Now, two of these men” – he gestured to the bedraggled soldiers under his command – “are no more than 16. It seems strange to quite a few people around here that none of your sons are in the Army.”

“Well, it don’t seem strange to me, with all the work there is to do around here,” said Anderson, squaring off with the Confederate Army officer. All social pretense now abandoned, Johnson became brutally candid.

“I’ll come right to the point,” he said. “I’ve come here to get ’em.” The grim announcement was greeted with contemptuous laughter from Anderson.

“I say something funny?” Johnson inquired, his face contorted in a smile that displayed an emotion generously removed from amusement.

Anderson favored Johnson with an assessing stare.

“You’re town-bred, ain’t you?” he asked.

“What’s that got to do with…” Johnson began.

“I have five hundred acres of good dirt here. As long as the rains come and the Sun shines, it’ll grow anything I’ve a mind to plant. And we pulled every stump, we’ve cleared every field, and we’ve done it ourselves, without the sweat of a single slave.”

“So?” interjected Johnson, who had neared the limits of his patience.

“So – so can you give me one good reason why I should send my family – that took me a lifetime to raise – down that road like a bunch of damn fools to do somebody else’s fighting?”

“Virginia needs all of her sons, Mr. Anderson,” said Johnson, quietly – as if that pious declaration would dissolve any remaining resistance. It had precisely the opposite effect.

“That might be so,” Anderson allowed, his voice assuming the quiet resolve of a patient man approaching the border of righteous lethal violence. “But these are my sons! Mine! They don’t belong to the state! When they were babies, I never saw the state coming around here with a spare tit. We never asked anything of the state, and never expected anything. We do our own living, and thanks to no man for the right. But … seein’ as you’re so worried about it – I’ll tell you, if any of my boys thinks this war is right, and wants to join in – he’s free to do it.”

The Confederate patrol moved on from the Anderson Ranch without securing a single recruit.

About a decade ago, several of my friends asked what I thought of the Mel Gibson (forgive me – is it legal to make a favorable public reference to him, or would that leave me subject to prosecution?) film The Patriot. In each case I replied that I considered it to be a very good movie with an exceptionally good soundtrack, but that I had liked it better in the 1965 version called Shenandoah, starring James “Don’t Call Me Jimmy” Stewart in the role of Charlie Anderson.

The two films are set in different wars and are separated by many details of plot and characterization, but the stories they tell are essentially identical: The widowed patriarch of a large southern family, after doing everything he could to protect his children from a war he wanted to avoid, is drawn irresistibly into the conflict after one of his sons is captured. Of the two, I consider Shenandoah the stronger and more poignant version, largely on the strength of its astonishingly perceptive anti-State message.

“When are you going to take this war seriously, Anderson?” inquired Lt. Johnson shortly before the exchange described above.

“Now let me tell you something Johnson, before you get on my wrong side,” Anderson replied, the ground beginning to shake in anticipatory tremors of his impending eruption. “My corn I take seriously, because it’s mine. And my potatoes and tomatoes and my fence I take note of because they’re mine. But this war is not mine and I don’t take note of it.”

During a visit to the grave of his wife Martha, who — unlike him — was a devoted Christian believer, Charlie speaks the unvarnished truth about the State’s defining abomination, war:

“I don’t even know what to say to you any more, Martha. There’s not much I can tell you about this war. It’s like all wars, I guess. The undertakers are winning. And the politicians who talk about the glory of it. And the old men who talk about the need of it. And the soldiers, well, they just wanna go home.”

Shenandoah came out in 1965, twenty years after the end of the Sacred Crusade To Save the Soviet Union and Create the United Nations, and at about the same time that our country was lied into Vietnam. It was adapted for Broadway ten years later, as the Communists consolidated their hold on Southeast Asia — the outcome that 500,000 Americans had died for the supposed purpose of preventing.

Last spring the musical version was staged at Ford’s Theater in the Imperial Capital with Scott Bakula (last seen as the oddly inept and non-charismatic Captain Jonathan Archer in the drab and forgettable Star Trek: Enterprise) miscast as Charlie Anderson.

And as one would expect of anything offered for public consumption in Washington, the

newest version of Shenandoah was subtly recalibrated to conform to the Imperial Party line.

Witness these comments from a review of the play published last April:

“What is worth fighting for? A way of life? A piece of land? Family safety? This question, as relevant to post-Sept.11 America as it was during the Civil War, is the basis for `Shenandoah’…. This war [the War of Northern Aggression] has nothing to do with them, [Charlie] Anderson says. His interest lies solely with the acres that he has cleared and cultivated. He put the farm together with his own hands; he doesn’t owe anybody anything. Let the rest of the world bleed and die. As long as his family is safe, Charlie Anderson will turn his back. Then his youngest son, mistakenly identified as a Confederate soldier, is captured by the Yankees. Now Anderson is involved…. The problem is that Charlie Anderson’s concerns are completely selfish. As long as his property is not destroyed or his family hurt, Anderson doesn’t care what happens to anybody else. He’s not standing on principle; he’s just looking out for No. 1.”

That assessment is what my kids would call a great big pile of “Number Two.”

That reviewer, who has the soul of a Stalin-era Soviet drama critic, juxtaposes Anderson’s supposed “selfishness” in refusing to let the Confederate press gang steal his sons (and later, beating with his fists a group of Scalawags who had come to plunder his livestock for the Bluebellies) with “Mr. Civic Responsibility” — that is, the man Anderson didn’t become, a dutiful statist drone willing to accept with docility whatever impositions the Almighty State saw fit to inflict on himself and his family.

In the collectivist lexicon, it is “selfish” for a father to protect his sons when the State seeks to abduct them to kill and die on its behalf.

It is likewise “selfish” for a property owner to protect his land and goods, legally acquired and developed through his own exertions, when the State seeks to waste them in the murderous folly of war.

Charlie Anderson, as portrayed by Brigadier General James Stewart (a World War II combat veteran who most likely wouldn’t have taken the role if he didn’t understand and share the character’s views, at least to some extent), embodies precisely the opposite of selfishness. With all due respect (whatever amount that might be) to Randians who consider Anderson an Objectivist Archetype, the character was actually a portrait in the noblest form of altruism: Selfless paternal devotion to hearth, home, and particularly children.

He was a uxorious husband, even after the loss of his wife; a stern but palpably loving father who was willing to fight and die to protect his children, but — and here’s the important part — wanted nothing to do with the death of other people’s sons. He despised both chattel slavery as practiced in the South, and the industrialized slaughter practiced by Lincoln’s regime (Lincoln and his regime were the descendants of the Jacobins, and the progenitors of the Bolsheviks).

Many of those who fought in the War Betweeen the States, particularly on the Southern side, were men like Charlie Anderson: Their allegiance, which has been described as telluric (“earthy” or “of the soil”) patriotism, was to particular people and specific places, not to grand abstractions like “Union” or even “The Cause,” as the expression was understood by the South.

By the war’s end, as Jeffrey Hummel has documented in his splendid study Emancipating Slaves, Enslaving Free Men, both the Federal and Confederate governments had degenerated into plunder-fueled engines of tyranny and corruption. War, whatever its stated objectives, always emancipates the State, to the detriment of liberty.

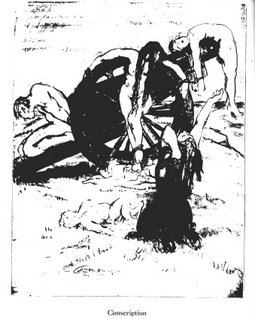

Unassailably noble as the Southern cause was (it is never justifiable to murder people because they no longer want to be part of your club), the Confederate government imposed conscription before the Union resorted to it, and its program involved not only the impressment of men but the seizure of property as well as the creation of what Karl Marx called “industrial armies.”

As someone who proudly displays a Confederate Battle Flag in his home, I offer that acknowledgment with some regret. On more than a few occasions as I have denounced conscription in the company of people whose views I almost entirely share, the Southern example has been cited to justify the proposition that in some desperate circumstances conscription has to be allowed.

But my respect for the South doesn’t leave me inclined to emulate their errors. Nor does it nullify the central moral argument against conscription: The State has no right to force people to kill and die on its behalf, and any government that cannot inspire volunteer efforts in its defense not only deserves to die, it must die. If the State can seize individuals through a draft, it can do anything else it pleases to anyone of its choosing, anytime it sees fit to do so.

As I have noted elsewhere, Lincoln’s draft was hailed by the New York Times in a July 13, 1863 house editorial (“The Conscription a Great National Benefit”)precisely because it removed all restraints on government power.

“It is a national blessing that the Conscription has been imposed,” declared this psalm in praise of the deified State. “It is a matter of prime concern that it should now be settled, once for all, whether this Government is or is not strong enough to compel military service in its defense.” Up until that point, “the popular mind had scarcely bethought itself for a moment that the power of an unlimited Conscription was … one of the living powers of the government in time of war. The general notion was that Conscription was a feature that belonged exclusively to despotic Governments….”

However, under the draft, “not only the property, but the personal military service of every ablebodied citizen is at the command of the national authorities, constitutionally exercised…. The Government is the people’s Government…. When it is once understood that our national authority has the right under the Constitution, to every dollar and every right arm in the country for its protection, and that the great people recognize and stand by that right, thenceforward, for all time to come, this Republic will command a respect, both at home and abroad, far beyond any ever accorded to it before.”

Pay careful attention to the order of priorities described above: The State has the right to every increment of wealth we possess, and every drop of blood in our veins, “for its protection.”

That’s what conscription means.

That’s why it is utterly un-Godly, documentably un-Constitutional, and morally impermissible.

That’s why any parent who doesn’t do everything he can to prevent the impending imposition of universal conscription is “worse than an infidel” (I Timothy 5:8).

Charlie Anderson, as portrayed by Stewart, was passionately anti-war, but not a pacifist. The same is true of millions of American parents, myself among them. I have no desire to kill or injure another human being, and pray that God grants me the blessing of finishing my life without staining my hands with human blood.

That being said, this must be also:

I would kill and die in defense of my country, but I wouldn’t shed a paper cut’s worth of human blood to defend the pack of degenerate gangsters who presume to call themselves “our” government. And as a Christian father it is my duty to prevent harm from descending on the family God has entrusted to me, if it resides within my power to do so.

There are only a few circumstances in which God authorizes us to kill, but in those circumstances, killing is mandatory. If I were to permit lethal harm to come to any member of my family when I could prevent it, I would be implicated in the blood guilt of that crime. This is why I will not, and cannot, permit the government to conscript my children for any reason.

I would kill any member of any armed gang who would violate the sanctity of my home for the purpose of abducting one of our children. It doesn’t matter what exalted title he would possess, or what tricked-out gang colors that gang-banger would wear. That principle, as John Locke would say, applies equally to both private sector gangs and those who operate under the supposed authority of the state.

It’s quite simple: If you threaten my kids, I’ll hurt you. If you try to kidnap them from me, I’ll kill you. Capice?

Content retrieved from: http://freedominourtime.blogspot.com/2006/08/these-are-my-sons_25.html.