After months of indecision, the Joe Biden administration has come out in favor of using international mechanisms to punish Russian officials for the “crime of aggression” in Ukraine. The White House has resisted Kiev’s effort to prosecute President Vladimir Putin and other Russian leaders at the International Crime Court (ICC) over fears that American officials could face similar accountability.

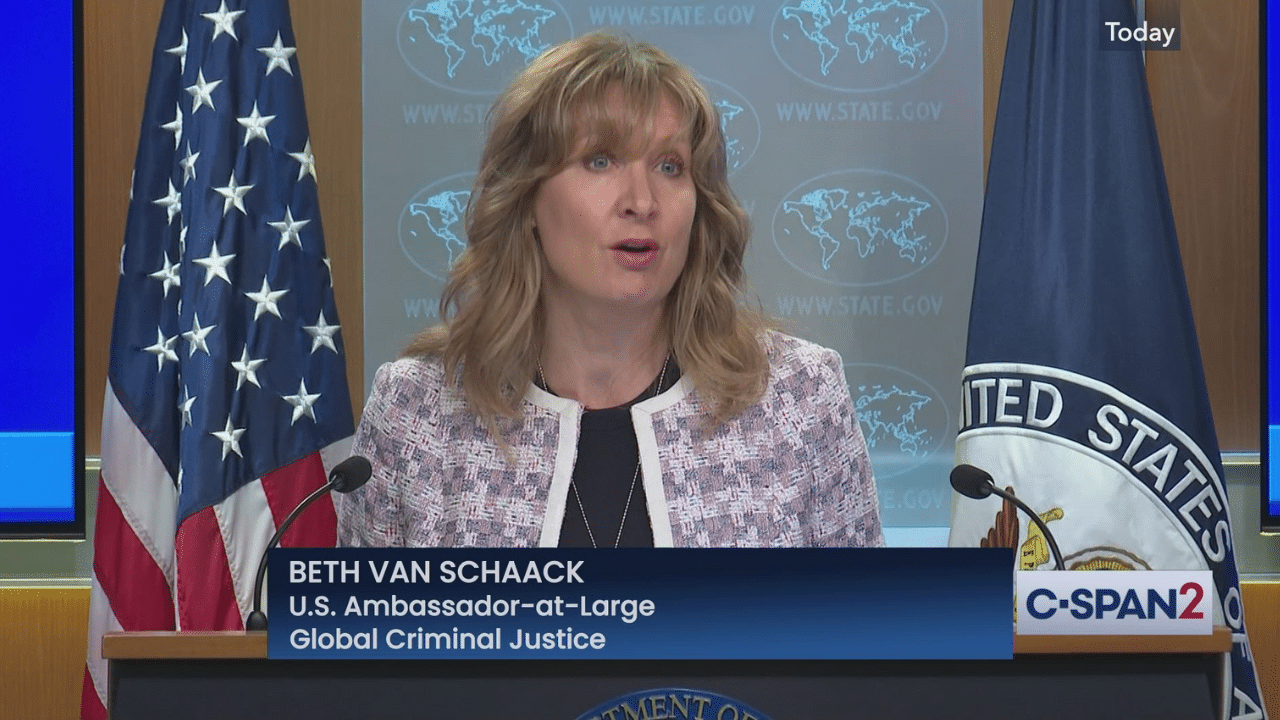

US Ambassador-at-Large for Global Criminal Justice Beth Van Schaack announced the decision on Monday. “At this critical moment in history, I am pleased to announce that the United States supports the development of an internationalized tribunal dedicated to prosecuting the crime of aggression against Ukraine,” she said, adding that “there are compelling arguments for why” the crime of aggression “must be prosecuted alongside” crimes that are being investigated by the ICC.

Van Schaack also discussed involving the Ukrainian judicial system and the European Union court in the prosecution. “We envision such a court having significant international elements – in the form of substantive law, personnel, information sources, and structure,” she said. “It might also be located elsewhere in Europe, at least at first, to reinforce Ukraine’s desired European orientation, lend gravitas to the initiative, and enable international involvement, including through [the European Union Agency for Criminal Justice Cooperation].”

Kiev and other Western countries have pressed the US and the ICC to put Russian officials on trial for months, but Washington has resisted signing on. Earlier this month, the ICC issued arrest warrants for Putin and Maria Alekseyevna Lvova-Belova, Russia’s commissioner for children’s rights, for allegedly kidnapping Ukrainian children.

At that time, the Department of Defense was blocking Washington from sharing information with the court over concerns that it might set a precedent allowing US troops to be prosecuted for similar actions. During the Donald Trump administration, the US sanctioned ICC officials for attempting to investigate American war crimes committed in Afghanistan.

Biden lifted the sanctions on the ICC but denounced the court for investigating both US war crimes in Afghanistan and the Israeli apartheid regime’s crimes against Palestinians, including large-scale massacres in the Gaza Strip.

The prosecution of Russian officials has also interrupted potential Chinese-brokered negotiations between Kiev and Moscow. Last week, Mykhailo Podolyak, an advisor to Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky, said that the ICC’s arrest warrant on Putin “means there will be no negotiations with the current Russian elite.”

As with Russia, the United States does not recognize the ICC. In 2002, President George W. Bush signed into law the American Servicemembers’ Protection Act, also known as the “Hague Invasion Act.” The bipartisan legislation went as far as to authorize military action against the Netherlands – a fellow founding member of NATO – to prevent US officials and military personnel accused of war crimes from facing accountability in an international tribunal.

The US has spent years pressuring other ICC member states to sign agreements refusing to ever surrender US troops to the court, in some cases even threatening economic sanctions, cuts in aid, or the withholding of US military assistance.

Washington has various restrictions in place preventing US cooperation with the ICC, although recent legislative adjustments have enabled an exception for the court’s “investigations and prosecutions” linked to the war in Ukraine. That inconsistent position has been challenged and criticized by organizations such as Human Rights Watch, which urged the Biden administration to ”set aside its objection” to the ICC.