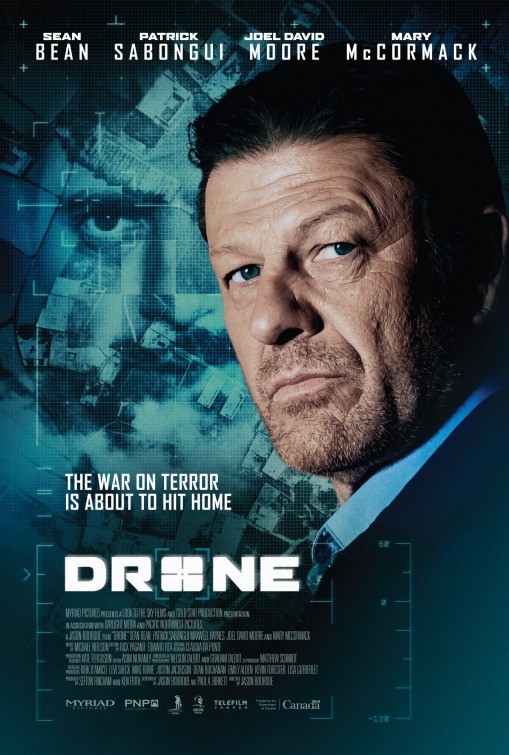

It’s probably about time for film makers to stop naming their critiques of drone warfare Drone. But that’s just a quibble—more a piece of practical advice than a substantive criticism. This latest installment in the “movies called Drone” series is directed by Jason Bourque and manages to offer some new twists on the many trenchant works created by thinking people appalled by the “lethal turn” in US foreign policy since September 11, 2001.

Assassination has been normalized as a standard operating procedure, a feat accomplished not by President Trump but by his predecessor, Barack Obama, whose administration mounted and implemented a complex bureaucratic institution of intentional, premeditated homicide of persons (usually of color) who are either suspected of complicity in terrorism, or suspected of association with persons suspected of complicity in terrorism. That’s right: the people being intentionally killed under the auspices of the US drone program outside areas of active hostilities fall into one of two categories: guilty until proven innocent, or guilty by association of being guilty until proven innocent.

Nearly all of the victims of drone strikes have been brown-skinned and of Muslim origin. It’s really quite astonishing that the first black US president could preside over such a flagrant program of racial profiling, which denies persons of color not only their right to life, but also their rights to defend themselves against the charge that they deserve to die, without indictment much less trial, for hypothetical crimes to which only the killers are privy. One can only hope that future historians will be suitably shocked by the total discombobulation of Western administrators in the aftermath of the terrorist attacks of 9/11.

In Drone (2017), a recent film version of the We Kill Because We Can story, many aspects of the US killing machine and how it has been used throughout much of the twenty-first century are highlighted, in the hope of provoking the viewer to reflect upon the significance of a paradigm of war which, despite being not only morally and legal but also strategically dubious, has come to be accepted by Western politicians and their voting constituents alike.

Sure, the drone warriors have managed to incinerate thousands of persons, mostly of unknown identity, but what have they really accomplished, beyond mass homicide and the enrichment of war profiteers? The Middle East is in shambles, Al Qaeda franchises have spored and spread, and the United States is fighting wars in at least seven different lands, while threatening others in various ways. Any sober assessment of US foreign policy over the past seventeen years can only conclude that the Global War on Terror (GWOT) has been an unmitigated failure. The primary tool of GWOT has been none other than the weaponized drone, which helped to usher in an era of executive war (formerly known as monarchic depredation, or tyranny) by allowing leaders both to wage war and deny that they are engaged in war at the same time and in the same place (for more on this, see the Libya intervention of 2011—or the bombing of Syria in 2018).

Along with the intended targets, Wistin has killed some unintended targets, which he and his co-workers perfunctorily label “collateral damage”. But the notion of collateral damage, dubious enough as it is, cannot truly be said to apply to cases of assassination. And no, it does not matter in the least that the implement of homicide is a military weapon. For in genuine combat contexts, where the lives of soldiers on the ground are at stake, collateral damage is said to be permissible because it is unavoidable, given military exigencies. The use of the category of “collateral damage” to excuse the people being mistakenly killed by weaponized drones outside areas of active hostilities is tantamount to asserting the right to kill anyone, anywhere, at any time, for whatever reasons the killers themselves deem sufficient. It is also a categorical denial of human rights.

The utter lawlessness of this paradigm will become more and more apparent as lethal drones spread around the globe and are used by leaders according to their discretion and caprice after kill committee meetings conducted behind closed doors and with neither transparency nor due process, following the example of mentor governments Israel and the United States. The drone killers act with complete impunity, for they are physically protected by their geographic distance from the places they fire on, and the secrecy of the program ensures that they remain anonymous, not only to their victims, but also to their family members and friends, as in the case of private contractor Wistin, who essentially leads a double life like any regular spy.

But is it really true that there are private contractors serving as drone operators and firing missiles upon people? If there were, we would not be told, for the citizens paying for this institution of death know as little as possible about the facts on the ground and the inner workings of the killing machine. This carefully maintained state of ignorance among the very people paying for the drone program is rationalized under State Secrets Privilege.

In a series of carefully plotted scenes, Drone (2017), like other films produced on this controversial topic in recent years, illuminates some of the lesser known and morally unsavory aspects of what has been going on:

-

Wounded survivors of initial strikes are taken out in double tap strikes, what can only be a violation of the Geneva Conventions. Of course the “quaint” idea that unarmed persons may not be summarily executed is ignored in the first strikes as well.

-

Persons are being spied on as though they had no rights or dignity whatsoever—whether or not they are suspected of terrorism.

-

The persons left bereft after strikes mourn the loss of their loved ones, who were, in reality, fathers, brothers, sons and, in the case of collateral damage victims not even suspected of complicity in terrorism: altogether innocuous women and children.

-

The killers are themselves never at risk of death when they fire on targets thousands of miles away, rendering dubious the rationalization used by combat soldiers throughout the history of warfare: that they must kill or else be killed.

-

The rebranding of assassination as targeted killing in warfare (dismissing innocent victims as collateral damage) but not really warfare (when it comes to oversight and congressional mandate) makes it nearly impossible for the citizens paying for this institution of premeditated homicide to understand what is going on. They are told that this is all a matter of national defense, and naturally throw their support behind anything carrying that label.

-

The military-age men killed—whether intentionally or unintentionally—are assumed to be terrorists, while the cases of collateral damage killing of women and children are systematically denied as “unconfirmed”, when not outright dismissed as terrorist propaganda.

These features of the drone program are variously highlighted in the film when a Pakistani businessman, Imir Shaw, whose wife and daughter were destroyed by a drone strike, travels to the United States to confront their killer. The unsavory truths being conveyed in Drone (2017) are easily verified, but the specific scenario devised to press these points is highly implausible for a variety of reasons. First, the Trump administration immigration gatekeepers would be unlikely to admit through the golden arches a military-aged male from Pakistan. Second, the man manages to locate his wife and daughter’s killer through hacking into the drone intelligence network, which, while possible, would be very difficult. Third, the layers of secrecy used to protect the perpetrators, including the very use of private contractors, makes it not at all obvious how such a victim could identify the precise person who pushed the button in any given case. The use of private military companies in the real-life drone program—if not in the acts of killing, at least in the generation of kill lists—makes it improbable that the name of the killers of any given victim will ever be revealed, even if the system is hacked (which is far more likely to be done by a whistleblower within the system than an outsider), and information is shared via an outlet such as Wikileaks.

Shaw also informs Wistin that his wife has been having an affair, which he has learned by spying on her prior to the visit, and that the wife and son have no idea what it is that Wistin does for a living. By pretending that his briefcase contains a bomb which he plans to detonate right then and there, Shaw ultimately drives Wistin to attempt to save his wife and son, which culminates in Shaw’s death.

The first half of Drone (2017) runs very slowly and seems a bit meandering, but serves to set the stage for the second half, which becomes more and more suspenseful as the viewer is drawn into the tense conflict between the American drone operator and the grief-stricken Pakistani man. The admittedly heavy-handed points made as the rather contrived plot unfolds are nonetheless important and need to be stressed, which is why I would like to see more people watch this film, despite its cinematic flaws. For the creators of this film are absolutely right about this: Until US taxpayers come to understand the reality of what they are funding under the label of “national defense”, these sorts of abominable crimes will continue to be committed.

The fact that the drone program has been so thoroughly shrouded in secrecy is not, as its administrators claim, itself a matter of national defense, but a means by which to secure compliance when, if presented with the facts, many proponents of drone warfare would withdraw their support. In the case of the US government’s killing machine, the American people have been hoodwinked to the point of coercion, which has undermined the democratic basis for the government’s alleged authority to act on their behalf. The apparent support of a policy or practice which is garnered through the use of deception willfully intended to sow ignorance is devoid of any legitimacy whatsoever. Nearly everyone opposes murder and supports justice, so when people are told by government officials that acts of murder are not acts of murder but instead “just war”, they have been horribly duped, no less than the drone operators seduced to enlist in the military using mythic images of the “noble warrior”, when in fact they will be transformed into contract killers.