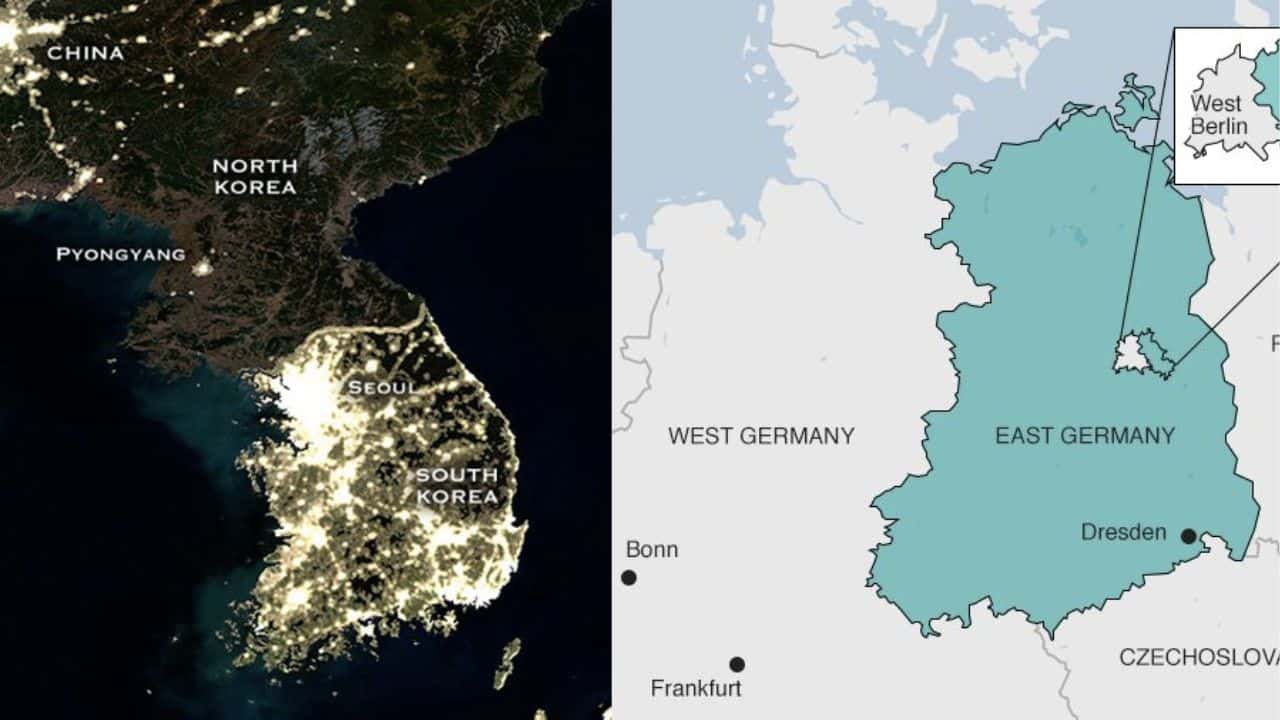

Institutions are, of course, in some sense the products of culture. But, because they formalize a set of norms, institutions are often the things that keep a culture honest, determining how far it is conducive to good behaviour rather than bad. To illustrate the point, the twentieth century ran a series of experiments, imposing quite different institutions on two sets of Germans (in West and East), two sets of Koreans (in North and South) and two sets of Chinese (inside and outside the People’s Republic). The results were very striking and the lesson crystal clear. If you take the same people, with more or less the same culture, and impose communist institutions on one group and capitalist institutions on another, almost immediately there will be a divergence in the way they behave.

Many historians today would agree that there were few really profound differences between the eastern and western ends of Eurasia in the 1500s. Both regions were early adopters of agriculture, market-based exchange and urban-centred state structures. But there was one crucial institutional difference. In China a monolithic empire had been consolidated, while Europe remained politically fragmented. In Guns, Germs and Steel, Jared Diamond explained why Eurasia had advanced ahead of the rest of the world. But not until his essay ‘How to Get Rich’ (1999) did he offer an answer to the question of why one end of Eurasia forged so far ahead of the other. The answer was that, in the plains of Eastern Eurasia, monolithic Oriental empires stifled innovation, while in mountainous, river-divided Western Eurasia, multiple monarchies and city-states engaged in creative competition and communication.

– Niall Ferguson, Civilization: The West and the Rest

Podcast: Play in new window | Download