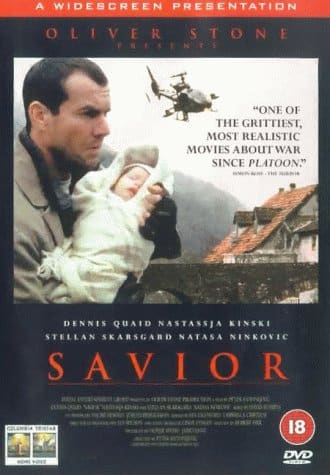

Righteous vengeance often spurs rage that spills blood endlessly. In the 1998 film Savior, revenge and the brutality of war steers our “hero” Joshua Rose, played by Dennis Quaid, into his redemption. After losing his family in a terrorist attack, Joshua walks into a nearby Mosque where he suspects those responsible to be and guns down a group of praying men. He escapes to join the French Foreign Legion where he learns to be a sniper. After his six years in the Legion are up, Joshua declares that he would like to “kill people that he hates for a change.” Cut to Bosnia, 1993. He fights for the Serbian nationalists against Bosnian Muslim militias and can continue to kill for vengeance against Muslims, whom Joshua holds responsible for his family’s death.

Joshua’s hatred sees him fighting alongside rapists and murderers. Whatever morality he had before the death of his family has become soured by his fatalistic hatred. This is not a review of what is an underrated film. Rather, it’s a look at the protagonist as a fictional example of how a man can become that which destroyed his own world. Joshua’s redemption comes when he rescues a mother and child from his fellow warriors. The Bosnian Muslim mother, Vera, played by Natasa Ninkovic, and her baby suddenly become human beings to him, as they would have been before his own family’s slaying. He sees them as deserving of life, not rape and murder.

In a terrifyingly graphic scene, a group of Bosnian civilians are murdered by Serbian militia men, including bludgeoning to death by a sledgehammer. We watch helplessly as Vera sacrifices herself while Joshua and her baby remain hidden; she sings a lullaby to calm the crying child until a “warrior” bashes her skull in with a hammer. Meanwhile, the Serbian commander is carelessly shaving in the distance. Moments later, the remaining unarmed civilians are gunned down. Hearing something, the murderers nearly find Joshua and the baby, and in an attempt to keep the infant quiet, Joshua nearly smothers it to death. Once in the clear, he desperately revives the child, the sweet innocent life which nearly became another lost statistic. The baby cries back to life. Joshua’s redemption is in saving a life, not in taking more. He protects and shields the child across the battlefield to safety.

War is the miserable ambition between those who seek many things, and revenge is often what spurs terrorism and reprisals. For a man like Joshua, revenge is a personal matter he seeks to punish collectively. When an enemy is defined as a religion or race of people, every single member of the pariah demographic becomes an inhuman threat. For instance, one Israeli Defence Force spokesperson referred to the children of Palestine as “snakes.” Even a child apparently possess deadly venom and surely will grow to be a predator.

In books such as Barbara F, Walter’s Reputation and Civil War, distant academic writing looks at civil war and separatist conflicts as “experiments” for a theory. To read such a book, one must remove themselves from the gore and tears of human experience to understand the planners need to create the semblance of balance and order, to understand clinically that which is ruled by passions. Such a theory determines why such conflicts are so violent. Yet, Robert Fisk in The Great War for Civilization repeats that one must first experience a wrong to seek justice. And just like vengeance, it’s a personal emotion, a motivator that can become generational.

On the other side of that, the imperialists have a sense of entitlement or even destiny. They can see an opportunity to push and expand their culture and civilization beyond the homeland, deep into what is decided to be a frontier, wilderness, or a “land without people.” Whether through religious dogma or a racial-ethno ambition, the conquest and expansion is in itself justification, fulfilling destiny. Victory and the eradication of the aboriginal is proof of a divine right, an inherent supremacy. Even if these victories were often at the expense of claimed principles, however it is achieved does not matter. When the defeated become a minority, as Bassem Youssef points out, that is when the native is empathized with. You can feel sorry for them when they are no longer a threat; powerless, without capability for revenge, and dependent on the conquerer.

If you marry both imperial entitlement with a need for vengeance you have Hitlerism, and what helped spur the rise and policies of German national socialism. The need for revenge can be massaged and invented, and may come from an event or defeat. A pariah group, whether that is defined by class, race, or religion, becomes the culprit. To be in constant conflict is in itself the key ingredient for most political ideologies, and war is a special place for them to grow and define themselves. Revenge can become policy for a state just as it is a doctrine for separatists, freedom fighters, and terorrists.

In order to accomplish the most horrible acts, one needs a sense of righteousness. That’s how millions of people can be killed without recourse or even shame. Global sympathy and tolerance for the United States was gained after the terrorists attacks in 2001. Whether those nations invaded by the U.S. in the aftermath, or the millions of people subsequently killed, had anything to do with the terrorism did not matter. The emotional endorsement of the world understood the need and intent of the U.S. government to take revenge, to bring the murderers and plotters to justice. That sentiment and energy was, as is often the case, cynically betrayed by the U.S. government to wage a war of hegemonic self-interest. Their actions have generated thousands of micro incidents of revenge, helpless rage, and brutal reprisals spurred by those who were wronged.

In a recent interview, Libertarian Institute Director Scott Horton mentioned the Yugoslav Civil War, the conflict that our movie’s protagonist finds himself fighting in, and where hatred and cycles of revenge polluted the land with bloodshed. Despite that, “they made it work,” as Scott points out. It was not easy, and animosity no doubt still exists, but most importantly the mass rapes and killing has stopped. Cries for revenge are not as loud as they were in the 1990s. Peace can reign, and despite humanity’s best efforts at destruction, nature does return. The saving of a baby is such a redemption. It should not matter whose baby is being rescued.

For those in Israel and Palestine, the cycle of killing is still on repeat. Make no mistake, there is no justification for the murder of the innocent, even if a faction claims they were killed “collaterally.”

Inside domestic borders we have the pretense of law and order, and even a murderer is granted due process. They as individuals are understood responsible for their actions. It would be considered obscene and unjust to bomb the suburb a murder suspect lives in, to kill anyone associated to them, or who looked like them. It is also considered immoral to execute them on the spot, without trial. Yet, here we are in a world where those who claim to base their entire system of existence on the rule of law can kill thousands without the scales of justice being balanced by due process—because vengeance demands it. It is the worse form of vigilantism where everyone is terrorized.

Maybe the moral to the story is that revenge is unfulfilling. Can you really kill them all in the end? Even if you understand who the them really is. The great disappointment is that those who sit with a straight face discussing civility and why government or theology is a path for good will support those who use both to wage terror and genocide. When a person takes it upon themselves to satisfy a personal blood lust, it becomes the policy, the cause, justice itself.

While the baby lives in The Savior, plenty more in the real world won’t. They will be blown to pieces, crushed or starved to death, apparently all of them deserving such a fate. Vengeance demands it and in time, those babies who survive will learn to seek revenge for themselves. That apparently is the wisdom of man and the policy of the civilized.