[P]eople started to believe that the bourgeoisie and its economic activities of trade and innovation were virtuous, or at least tolerable. In every successful lurch into modern riches from Holland in 1650 to the United States in 1900 to China in 2000, one sees a startling revaluation in how people thought about exchange and innovation.

“How the Bourgeois Deal Enriched the World”

Art Carden and Deirdre Nansen McCloskey

Perhaps it’s time for another, similarly positive reevaluation of exchange and innovation. Heaven knows we need it. Our age features a distinct lack of appreciation of trade through the global division of labor, the innovation and prosperity it produces, and the signs of entrepreneurial success, namely, the wealth of innovators. We have witnessed a surge in good feelings toward socialism and various socialism-lites despite their unbroken record of death, oppression, and stagnation.

Could the varied opponents of market-liberalism—libertarianism in its purest form—suffer an allergy to what Adam Smith identified as a key feature of the “system of natural liberty”? In The Wealth of Nations Smith famously observed,

It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker, that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest.

Apparently, for people who dislike the market economy, producing even astounding benefits for others does not count if one does it at a profit. That is strange.

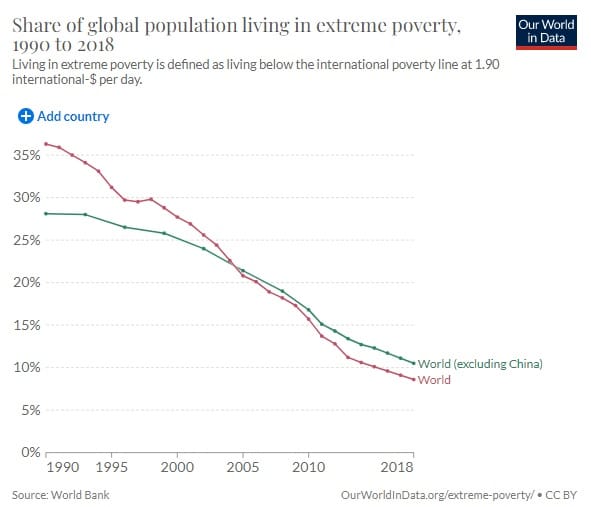

In 1900 about 80 percent of the world’s population lived in extreme poverty. Today, less than 10 percent does. The reduction since the 1980s alone has been phenomenal. And during that time the world’s population has grown dramatically —from under 2 billion in 1900 to 8 billion today!

Deirdre McCloskey and Art Carden write that since 1800 per-capita wealth has increased by 3,000 percent. Per capita! (They explain how and why in Leave Me Alone and I Will Make You Rich: How the Bourgeois Deal Enriched the World. Also see this.)

Malthus and Marx must be spinning in their graves. Paul Ehrlich, still alive, declared in the late 1960s that “the battle to feed all of humanity is over.” About that prediction, Maxwell Smart would have said, “Missed it by that much.” (Ehrlich still gets treated by the news media like an oracle.)

Do people know about this marken-driven progress? Did the establishment and alternative media report it? I must have missed it.

The eradication of poverty has many freedom-related reasons. Economic liberalization (marketization), that is, the freeing up of entrepreneurship and trade deserves much credit. But something else was also required. Economic historian McCloskey primarily credits a change in attitude toward the “bourgeois virtues,” such as innovation. “In every successful lurch into modern riches from Holland in 1650 to the United States in 1900 to China in 2000,” McCloskey and Art Carden write, “one sees a startling revaluation in how people thought about exchange and innovation.” Envy and resentment at success diminished, freeing people to innovate, trade, and get rich while making consumers better off. Mass production emerged for the first time in history. Producers didn’t work just for the political elite. How great was that?

Let’s put it another way: poverty has been eradicated at a profit! Was that virtuous? Would it have been more virtuous had it been done by nonprofits? The antipoverty record of nonprofits, especially governments, is dismal.

Where is the praise for the market from all the usual antipoverty voices? I can find only one voice, however grudging: Rock star Bono, who said in 2022:

There’s a funny moment when you realize that as an activist: The off-ramp out of extreme poverty is, ugh, commerce, it’s entrepreneurial capitalism. I spend a lot of time in countries all over Africa, and they’re like, “Eh, we wouldn’t mind a little more globalization actually. I would point out that there has been a lot of progress over the years.” . . . Capitalism is a wild beast. We need to tame it. But globalization has brought more people out of poverty than any other -ism. If somebody comes to me with a better idea, I’ll sign up. I didn’t grow up to like the idea that we’ve made heroes out of businesspeople, but if you’re bringing jobs to a community and treating people well, then you are a hero.

As I said, grudging, but better than nothing. But did Bono’s friends and fans become pro-market? I don’t see it.

One might expect that in a world of scarcity, a system of political economy that harmonizes diverse interests and creates widespread wealth from those differences to win enthusiastic praise. But no. Enthusiasts for markets and economic success have been scarce throughout history because a relative few succeed fabulously as innovators while most others merely succeed as consumers—beyond their recent ancestors’ wildest dreams.

“People before profits!” shout envious ignoramuses, who can’t be bothered to figure out that businesses that fail to please people record losses, not profits, and go bankrupt. It’s a profit–and-loss system (unless the government violates the system by intervening).

By the way, pure entrepreneurial profit emerges when a business can sell its goods for more than its costs, including wages. That is, an entrepreneur happens upon a discrepancy between the price (valuation) of inputs and the price buyers are willing to pay for the output. Hence my battle cry: Exploit price discrepancies, not people!

However, some find it more satisfying to look for exploitation in any encounter whether it is there or not. Sellers exploit buyers; employers exploit employees. It requires no proof because it is a sacred article of faith. The faithful are blind to the deep harmony of interests of sellers and buyers, of employers and employees. They need each other because the system of natural liberty, even when burdened by state intervention, makes all parties richer than they ever could be without the market, its prerequisites (respect for others and their property), and its consequences (the global division of labor).

Getting back to Adam Smith’s point, what could be the objection to trade based on mutual benefit? Why should anyone expect the butcher, baker, and brewer to live for their customers? Like their customers, they have lives and families too. Are sellers wrong because they don’t give away their wares? Do their customers give away their products and services? Then what’s wrong with charging what “the market will bear,” that is, what people are willing to pay?

We all agree that no one can own other people. If you want something that belongs to another person, you offer to trade. Just as you don’t own other people—that’s called slavery—you also don’t own their belongings until they accept the terms of trade. Governments often seek to set the terms of trade, but it has no legitimate power to do so. Governments are usurpers. The terms are up to the parties because the parties are trading their property. (If they violate the rights of nonconsenting third parties, that’s a matter for the courts.)

Smith didn’t mean that buyers and sellers can’t be friendly or care about one another. His point was that benevolence is not necessary for mutually beneficial exchanges. It would take place anyway. All that’s required is the realization that trade is positive-sum. Each exchanges something less-preferred for something more-preferred. Person A gets what he wants by offering to Person B what he wants, and vice versa. One serves one’s interests by figuring out what’s in other people’s interests. The pursuit of self-interest serves the interests of all. That’s one fine arrangement.

Somebody once said that if America is worth saving, it’s worth saving at a profit. That goes for the whole world.