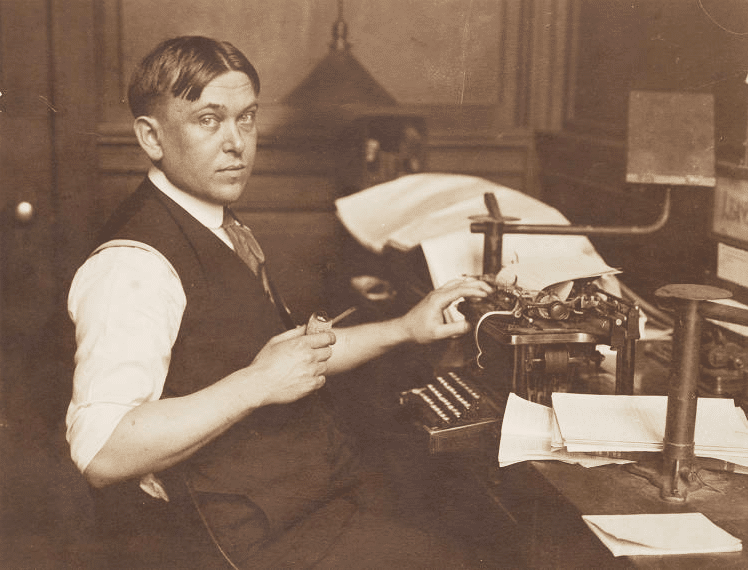

Henry Louis Mencken was born in Baltimore on September 12, 1880. After completing only a few years of formal schooling, he taught himself the craft of journalism and, by the age of eighteen, was working as a reporter for the Baltimore Herald. Over the next four decades Mencken produced millions of words in newspapers, magazines, and books. He cut his teeth as a critic in the six‑volume series Prejudices, edited the literary magazine The Smart Set, and founded The American Mercury. While he admired the energy of American speech, he refused to flatter his countrymen. “Boobus Americanus,” he called them—a crowd of conformists too easily swayed by politicians and preachers. Mencken’s aphorisms, drawn from essays, notebooks, and letters, remain some of the most pungent commentaries on democracy, politics, reform, and human nature.

As an editor and scholar he left a broader cultural imprint. At The Smart Set and later The American Mercury he published work by F. Scott Fitzgerald, Eugene O’Neill, and Langston Hughes, and he baited the censors by mailing banned issues to himself to provoke a court fight. His linguistic study The American Language (1919) treated American speech as an evolving idiom rather than a corrupted dialect, tracing how regional slang, immigrant vernaculars, and colloquialisms formed a dynamic national language. By celebrating everyday usage, he invited readers to take pride in linguistic innovation and to question received standards.

Mencken never trusted plebiscitary government. In his diaries and essays he defined democracy as “the theory that the common people know what they want, and deserve to get it good and hard.” To him majority rule was less a noble experiment than a mechanism for sanctifying folly. In the wake of World War I he observed that mass politics elevates mediocrity. He dismissed lofty theories about popular sovereignty by writing that “democracy is a pathetic belief in the collective wisdom of individual ignorance.” Elsewhere he compared the ritual of voting to a religious ceremony in which jackals worship jackasses. These lines were not off‑hand jokes but the distilled judgement of a writer who had covered elections and conventions for decades.

His contempt extended to the candidates who sought office. Mencken likened campaigns to market days in a thieves’ bazaar. “Every election is a sort of advance auction sale of stolen goods,” he wrote. The phrase captures his view that public office is a racket that redistributes wealth from productive citizens to political allies. In his notebooks he returned to the theme, insisting that “a good politician is quite as unthinkable as an honest burglar.” The moral world of politics seemed hopeless: officials were plunderers by definition, and elections were auctions of other people’s property.

Mencken’s disdain for democratic leaders reached its apogee in 1920. Writing in The Baltimore Evening Sun under the headline “Bayard vs. Lionheart,” he argued that national campaigns rewarded the most devious candidates because they could appeal to vast electorates only through slogans. “The larger the mob, the harder the test,” he wrote; “as democracy is perfected, the office represents, more and more closely, the inner soul of the people.” He predicted that “on some great and glorious day the plain folks of the land will reach their heart’s desire at last, and the White House will be adorned by a downright moron.” This jeremiad, reprinted in the anthology On Politics: A Carnival of Buncombe, encapsulated his belief that the ballot box would ultimately deliver what voters deserved.

His disdain for officeholders was matched by his shame at being governed by them. In a line later collected in A Mencken Chrestomathy, he declared, “Every decent man is ashamed of the government he lives under.” Though the remark lacks the gallows humor of his other quips, it reveals the seriousness beneath the sarcasm. Mencken saw government not as a necessary protector of rights but as a predatory institution that preys on the industrious.

Mencken distrusted systems that promised simple solutions to complex problems. In an essay from Prejudices: Second Series he lamented the search for tidy explanations in art and life: there is, he wrote, “always a well‑known solution to every human problem—neat, plausible, and wrong.” The aphorism suggests that public policy cannot be reduced to a formula; attempts to legislate morality or engineer prosperity will misfire because reality is irreducibly complicated. Later compilers paraphrased his warning as “for every complex problem there is an answer that is clear, simple, and wrong,” but the point remains: the most seductive answers are often the least accurate.

Mencken believed that the appeal of simple solutions rested on a deeper trait of human nature: a craving for security over liberty. In his notebooks he observed that “most people want security in this world, not liberty.” For him the average citizen preferred the comfort of dependence to the risks inherent in freedom. That preference explained why grand schemes for social insurance and moral reform gained traction despite their encroachments on individual autonomy. Mencken’s pessimism about human courage has been echoed by later critics who note how readily voters trade freedom for the illusion of safety.

If Mencken distrusted electorates, he was equally wary of reformers who claimed to act on behalf of humanity. In his posthumously published notebooks, collected as Minority Report, he distilled his suspicion into a single sentence: “The urge to save humanity is almost always only a false‑face for the urge to rule it.” Those who sought to uplift mankind, he argued, invariably wielded power in order to impose their tastes. Missionaries, progressive reformers, and prohibitionists all disguised their lust for domination under the mask of benevolence. By exposing the authoritarian impulse behind utopian schemes, Mencken anticipated later critiques of social engineering.

Mencken’s wariness of messianic politicians grew out of his conviction that moralism is a cover for coercion. In the same notebook entry he elaborated that messiahs seek “not the chance to serve” but power. To Mencken, moral crusades were a form of intellectual hubris; they assumed that one person or party knows what is best for everyone else. His writing during the 1920s attacked temperance advocates and censors with equal ferocity, arguing that no class of moralists should dictate the private behavior of citizens. Readers who chafed under prohibition and blue laws found solace in his insistence that freedom includes the right to make one’s own mistakes.

Mencken’s sneers at democracy and reform did not translate into apathy. He admired the iconoclast who resists herd opinion. In a 1919 essay on modern poetry he confessed that “every normal man must be tempted, at times, to spit on his hands, hoist the black flag, and begin slitting throats.” The line, buried in a review of Ezra Pound, is hyperbolic but revealing; he saw the call of rebellion as natural when confronted with stupidity and conformity. The image of raising the black flag evokes piracy and defiance; it urges readers to reject the pieties of their age and embrace intellectual combat. For Mencken, genuine creativity and independence require a willingness to stand apart from the mob.

His skepticism about government took a philosophical form as well. In a 1922 essay titled “Le Contrat Social,” he argued that “all government, in its essence, is a conspiracy against the superior man.” The most dangerous citizen, he continued, is the one who can think for himself without regard to prevailing superstitions and taboos. Such independence threatens rulers because it exposes the irrational foundations of their authority. Mencken therefore concluded that the ideal political order “leaves the citizen alone.” These lines, published in an era of expanding federal power, showcase his libertarian instincts. They also illuminate the elitism that undergirded his philosophy: he believed that talented individuals should be free from interference, even if most people were content with mediocrity.

Mencken’s birthday invites both celebration and reflection. He was a self‑taught newspaper man who championed artistic modernism, defended free speech, and mocked the pretensions of his era. His definitions of democracy and politics continue to circulate because they capture something permanent about public life: elections often reward charisma over competence, reformers are drawn to power, and voters frequently exchange liberty for security. His skepticism was not nihilistic but rooted in a fierce individualism. He hoped that some readers would respond to his barbs by taking up the black flag of independent thought. To revisit Mencken’s words is to encounter a writer who distrusted majorities, loathed moral busybodies, and prized the autonomy of the mind. That combination of irreverence and principled dissent remains as bracing today as it was in his own roaring twenties.

I’ll close with a Mencken quote gifted by historian Dave Benner:

“Let us not forget that it is oratory, not logic; beauty, not sense. Think of the argument in it! Put it into the cold words of everyday! The doctrine is simply this: that the Union soldiers who died at Gettysburg sacrificed their lives to the cause of self-determination – “that government of the people, by the people, for the people,” should not perish from the earth. It is difficult to imagine anything more untrue. The Union soldiers in that battle actually fought against self-determination; it was the Confederates who fought for the right of their people to govern themselves.”