Since the end of the Cold War in 1990, US defense spending has increased 182 percent in nominal terms, and 44 percent in inflation-adjusted terms. In inflation-adjusted terms, defense spending is now about equal with the all-time peak reached in 2011, and the White House’s Office of Management and Budget estimates that defense spending will reach an all-time high in 2020.

Source: Office of Management and Budget, Historical Tables, Table 3.2.

In 2018 dollars, defense spending hit approximately $942,198 — which includes “homeland defense” spending and spending on veterans. It can soon be expected to top a trillion dollars every year.

Source: Office of Management and Budget, Historical Tables, Table 3.2.

Thanks to Donald Trump’s budget deals with the Democrats, which paves the way for even more lavish use of taxpayer money, defense spending increased 9.9 percent from 2018 to 2019.

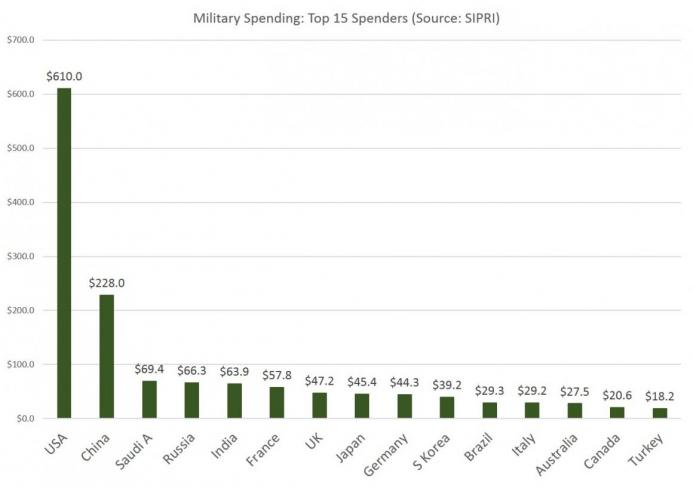

Meanwhile, based on conservative 2017 estimates of spending from the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) — which ignore spending on veterans, for instance — the US spent 610 billion dollars, while China spent 228 billion. The rest of the list engaged in miniscule amounts of spending by comparison, with Russia spending 66 billion, the UK spending 47 billion, and Japan spending 45 billion — to list a few examples.

Source: SIPRI, totals are in billions of dollars.

In other words, US politicians spent more on defense than the next seven biggest spenders combined. And most of those other spenders are consistent allies.

And, of course, the US government has an enormous stockpile of nuclear weapons, which, as Dwight Eisenhower understood, is essentially an impenetrable deterrence against an existential threat against the US government.

Nevertheless, in the wake of this year’s budget deal, researchers from the American Enterprise Institute claimed the binge still was not enough. For them, a trillion dollars per year is just barely enough to “avoid outright disaster.”

After all, a trillion dollars simply isn’t enough when the “National Security Strategy” is to be ready to launch three wars at once: in Europe, the Middle East, and East Asia.

There is no upper bound on spending with these perennial advocates for what is essentially unlimited spending on the military.

Socialist Military Planning

The “correct” amount of spending, of course, is totally unknown. We’re just told it’s a bigger number than what is now being spent. But how could a correct number be known? The defense economy is socialist in the strict, technical sense of the term. Defense “services” are provided either by government owned or government-funded agencies and firms only. There is nothing resembling market competition, and the amount of spending has no connection whatsoever to anything that might be described as market demand. Spending targets and totals are simply numbers plucked out of the air by central planners with the help of lobbyists from organizations that benefit from the largesse.

But don’t worry. Friendly hawkish economists provide theoretical cover for the total disconnect between those who spend the money and those who pay all the bills. Economist Mark Hendrickson, who also decries the recent budget deal as offering far too little in new spending, sums up the rationale for endless spending in two sentences: “You can argue that the federal government spends too much on defense. That is an unknowable except in retrospect, but the cost of spending too much on defense is almost certainly less than the cost of not spending enough.”

This sounds clever, but it’s not true.

Defense spending does not exist in a vacuum, and increased spending on “defense” isn’t politically neutral. Nor does additional spending translate only to defensive capability held in storage somewhere waiting to be brandished only when the state is threatened.

[RELATED: “Public Goods, National Defense, and Central Planning” by Richard Ebeling]

In practice, when a military force is sitting on a huge pile of cash and equipment, the temptation to use those resources — even when facing no real military threat — is much greater. This tends to increase paranoia in other states which then launch reactive efforts to increase their own defense spending in response to a competitor states.

In the case of the US, of course, the US has shown in recent decades that it is enthusiastic about invading other sovereign states on a fairly regular basis. And when it isn’t launching new wars, it is talking about it, as in the cases of Syria and Venezuela. Even in cases where full-scale war is averted, as in Syria, the US still asserts it can violate local air space and even land troops within the country’s borders whenever it wants.

The case of the 2011 US invasion of Libya, for example, is instructive. In Libya, we were told the brutality of the Qaddafi regime required immediate military intervention, without so much as a debate in Congress. Fortunately, offensive military weapons were all set to start another US military invasion on the other side of the planet.

The operation, of course, did nothing to enhance US defense, nor did it help ordinary Libyans. The failure of the invasion is now admitted even by one of its chief architects, the Hillary Clinton disciple Samantha Power, who now says: “We could hardly expect to have a crystal ball when it came to accurately predicting outcomes in places where the culture was not our own.” Translation: the war failed.

Indeed, the US’s huge military buildup since 9/11 overall has not actually made the US any safer. Writing in March for The New Republic, Stephen Wertheim pointed out how the new military thinking of that time was based on the idea establishing global military primacy for the US. Once this can be done, other threats will wither away. That, of course, didn’t happen:

[Then-US Deputy Secretary of Defense Paul] Wolfowitz and his Pentagon colleagues originally justified their focus on primacy by claiming that it would bring peace. In a draft of their report, called the Defense Planning Guidance, they argued that the United States should seek a preeminence so overwhelming as to prevent any potential rival from even “aspiring to a larger regional or global role.” After a public outcry, the final language was softened. But at least policymakers back then felt some compunction to demonstrate that Pax Americana would live up to its name.

Decades later, the opposite has transpired. America spends more on defense than the next seven countries combined, with roughly 800 bases ringing the globe, yet its might has not prevented China from rising nor Russia from asserting itself, and may have antagonized both. Instead of cowing others into peace, primacy has plunged America into war. It has forced the United States to resist any significant retraction of its military power, lest it lose influence relative to anyone else. The endless wars are endless because the United States has appointed itself the world’s “indispensable nation,” in Secretary of State Madeleine Albright’s formulation, responsible less for ensuring its own safety than for maintaining its material and moral privilege to police the world. The costs include 147,000 lives in Afghanistan and $5.9 trillion for a war on terror that has stretched on since 2001, according to Brown University’s Costs of War Project.

It would be nice if more military spending could convince other large states to give up and go home, but that’s not how nationalism works.

Thus, contrary to Hendrickson’s formula, it turns out the cost of “too much spending” extends far beyond the mere dollar amount over the theoretical “correct” amount of spending. Instead, military spending itself creates a need for even more spending.

The Economic Cost

Meanwhile, the advocates for endless spending on new military projects ignore the many economic costs military spending imposes on the domestic economy.

As with all government spending, defense spending bids up the prices of raw materials used in all industries, not just defense. A huge military makes steel, for instance, more expensive to the private sector. Government spending also hires away workers from the private sector. This means engineers who might have been working on products designed to improve the lives of ordinary people are instead busy building weapons that will be used to bomb yet another dirt poor no-threat country on the other side of the world.

And then there are the veterans themselves, of course, who now will spend years in and out of filthy VA hospitals to treat both physical and mental ailments brought on by wars — like the Iraq War — which only served to increase the power and footprint of organization like Al-Qaeda.

We have no way of calculating the economic drag imposed on the private sector over time, and this is unfortunate since economic power is the most important factor in determining long-term military power. As foreign policy scholar John Mueller noted in his book Atomic Obsession, the Soviets during the Cold War were not primarily deterred by the size of the US conventional military, or even by its nuclear arsenal. Instead, they were deterred by the “the enormous potential of the American war machine” which existed not in already-made weapons, but in the form of the world’s largest economy.

In other words, the best defense is a capitalist one in which enormous amounts of wealth make it clear that the potential for successful warmaking is enormous. Or, as Ludwig von Mises wrote in Interventionism: “When the capitalist nations in time of war give up the industrial superiority which their economic system provides them, their power to resist and their chances to win are considerably reduced.”

Unfortunately, today’s hawks insist it is now always wartime, and they demand the tax collectors expropriate ever larger amounts of Americans’ wealth in order to carry out their version of military readiness. What is the total cost such such relentless spending on the private sector? We don’t know for sure, and neither do the hawks. Since they’re the ones who want more of the taxpayer’s money, the burden of proof is on them.

At the very least, however, a good place to start is to demand an end to the US policy of using its enormous military to constantly threaten, invade, and coerce foreign nations. Fortunately, a military like that is unlikely to cost a trillion dollars per year.

Reprinted with permission from the Mises Institute