During Iraq War II (2003–2011), in addition to thousands of American soldiers and contractors who died, more than 100,000 Iraq civilians were killed. This number is consistent with independent counts as well as leaked Pentagon data (sources available at Wikipedia). However, more sophisticated studies which combined data sets and methodologies from multiple independent efforts have produced a total estimate of deaths (from 2003-2018) of 1.5-3.4 million people. This does not count the combatants who died fighting against what many consider to have been a foreign invader conducting an illegal occupation (or those fighting in unavoidable civil conflict caused by the invasion).

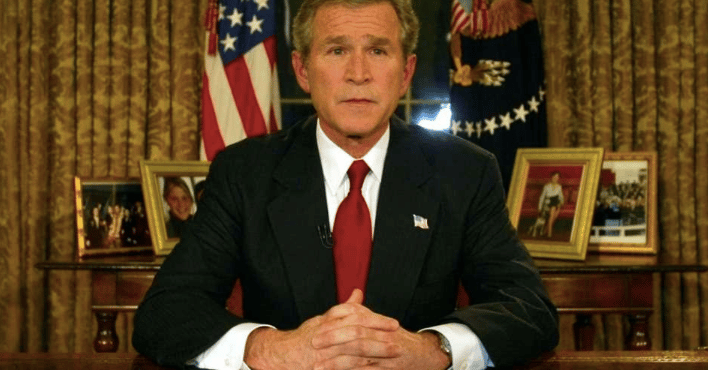

There’s no question about this war being a massive human tragedy, a catastrophe of choice, a milestone of unholy slaughter in the early history of the 21st century. This slaughter is intimately associated with the leader who started it: George W. Bush. The question remains, how could one man be so evil?

Bush’s guilt can be evaluated by examining his motives. Why did he do it? Did he really believe that WMDs were in Iraq? Did he want to avenge his daddy? There is in fact a clear answer to this question.

The purpose of the Iraq war was to flex American muscle. The neoconservative vision of American hegemony seeks to use American military power to enforce its desired policies abroad. Neocons believe that if the military is never used in pursuit of American policy objectives then it’s a waste of money and a sign of weakness that would invite predators of their ilk from other powers to prey on the so-called free world. In the post-Cold War environment where America had emerged as the world’s sole superpower, Iraq was the ideal opportunity to show the world that America means business. This rationale is cold, cynical and indifferent; neoconservatism is a policy position, possessing a realist morality that washes its hands of any concern for common people.

According to neoconservatism, the harm caused to common people by military intervention is morally unimportant. Neoconservatives believe that people who live in geopolitical problem areas would face moral deprivations from their own bad governments anyway. They believe that it doesn’t matter – really – whether one dies by Saddam Hussein’s secret police, or by an American bomb. To neoconservatives, the world is a better place when America is in charge. With a single rationalization, neocons willfully exclude concern for common people from their policy formulations.

The cynical moral view of Neoconservatism is consistent with Hannah Arendt’s notion of, “The banality of evil.” This phrase comes from a book Arendt wrote about the Jerusalem crimes against humanity trial of Holocaust facilitator Adolf Eichmann, an SS officer who coordinated the logistics of moving populations of Jews into eastern camps. In the book, she points out how average Eichmann was. He did not possess high intelligence and lived his life as a joiner. He was not particularly anti-Semitic, showed no signs of psychopathy and generally got along well with other people. He had carried out his role in the Holocaust purely out of a quiet commitment to his bureaucratic duty in the larger society in which he took part. Arendt calls evil banal because it is, in this case, neither a product of psychopathic or hateful intent nor can the mild-mannered conduct of Eichmann be remotely morally justified. In the end, Arendt claims that Eichmann’s evil is connected to his profound moral stupidity.

Hannah Arendt’s analysis of Eichmann’s moral status provides insight into George W. Bush’s moral guilt.

With perhaps over a million innocents dead because of a policy-driven, unnecessary war, Bush has the status of a moral monster. Yet, Bush’s evil is particularly banal. This kind of evil would not be recognized by its vicious fangs or wicked scowl. It is an evil that is unassuming, bungling even. Preventing this kind of person from having power requires special attention to what makes them so evil.

In 2013, Ron Fournier penned an article in The Atlantic arguing that George W. Bush was a good man. During a 2002 press conference, Mr. Fournier and a colleague stood to mark Bush’s entrance to the room, while other journalists and foreign press remained seated in smug protest. Bush handwrote a note to each man, thanking them for at least honoring the dignity of the office of the Presidency. Bush was known for small gestures of respect, from punctuality, to requiring a simple dress code for the Oval Office. Fournier argues that Bush had a sense of decency, not wanting to interrupt Fournier’s family time for an interview, for example, and also taking time to visit with the families of slain soldiers.

It seems incredible that a man guilty of such crimes against humanity could be perceived as decent. This represents a clue to understanding banal evil. The gestures to which Ron Fournier refer hardly absolve George W. Bush of his status as a possible moral monster, but they do hint at the possibility that Bush has some sort of moral compass. What’s the relationship between Bush’s crimes and that compass? If Bush truly has any sense of decency, how could he have launched the Iraq War? Philosophy can provide an answer.

Stanford University’s philosophy department runs an online encyclopedia of philosophical definitions. One entry discusses the conscience, or moral compass.

“Through our individual conscience, we become aware of our deeply held moral principles, we are motivated to act upon them, and we assess our character, our behavior and ultimately our self against those principles.”

Conscience involves one’s own self-awareness of one’s deeply held principles. Being aware of some moral principles does not imply that one would be aware of all possible moral principles. Everyone has a unique moral self-identity, a sense of what’s right and good, and a sense of where one stands on the spectrum of good and evil. Conscience is a connective tissue. It relates the moral principles in which one believes, to one’s perception of one’s own identity. Through conscience, one constructs a sense of identity out of chose moral principles. A moral compass serve not only to guide choices, it also is a tool for self-reflection.

Our moral beliefs also contribute to how we perceive others. We judge others based on where we believe they stand on the spectrum of good and evil, and in some cases we use our perception of others to reflect back on our own sense of moral identity.

“More recent psychological studies have suggested that people tend to link the identity of others not so much to their memories, as traditionally believed, but to their morals: it is the loss of one’s moral character and moral beliefs, rather than of one’s memory, that leads us to say that a certain individual is not the same person anymore (Strohminger and Nichols 2015). These findings provide empirical support to the idea that conscience is essential to one’s sense of personal identity and to attributions of personal identity.”

According to the psychological research discussed above, one’s sense of identity can have less to do with actual actions, and more to do with one’s chosen moral beliefs. If someone could associate their own identity with the identity of others holding a particular moral worldview, then one could calibrate their moral compass to reflect differently on their own life. If you tie your identity to those you morally admire, you can partially absolve yourself of a degree of moral accountability. You concede moral responsibility to a larger group, which also means conceding moral reasoning – including feelings of guilt or accountability – to that group. When confronted with the guilt of your particular actions, you simply defend the tribe’s power, and ignore morality.

In recent years, George W. Bush has taken up painting at a hobby. This past autumn, some of Bush’s paintings were displayed at an exhibit at the Kennedy Center. These painting featured scenes of America’s military veterans, including many wounded warriors. This Portraits of Courage exhibit demonstrates Bush’s quiet obsession with the men and women wounded in wars, many of whom he sent off to fight.

“Command Sergeant Major Brian Flom was wounded in the face by a rocket attack in Iraq in 2007.

“‘That was the easy part,’ he said, standing beside a painting in which he appears with fellow military personnel, one of dozens of works on display at the Kennedy Center in Washington, DC.

“‘The challenging part was the TBI [traumatic brain injury] and the post-traumatic stress that accompanied a lot of time spent in a combat zone.’

“Recovery is ‘still going on – it’s an everyday process, right, and some days are better than others.’

“Flom was selected to go on a mountain bike ride with Bush in 2015 and has now met him ‘many times,’ including dinner at the former president’s house.

“Bush ‘decided one day to paint people that he had a connection with and meant something to him, and here I am.’”

Bush is spending his retirement connecting to the people who were wounded in wars. This connection is interesting, because it relates to the perceived moral identity of these people. These paintings are a way for Bush to tie his identity to the moral status of veterans.

Bush’s painting hobby began much earlier. Infamous among leaked images of the former president’s early paintings are bizarre self-portraits of the man in the bathtub and shower. The images portrayed are toes sticking up from the water, and also one in which the back of his head is shown, his face barely appearing in a mirror. These paintings show a sense of detachment, unclear identity, and a desire to wash away something unclean.

It’s possible that ‘W’ himself has been facing a small crisis of conscience, and uncertainty about his own moral identity, spurred by a sense of moral guilt. The paintings might have been a therapy, to concretize the feelings. As he developed the hobby, Bush sought to relate to the moral identity of the soldiers he admired.

By connecting to the moral values of those who sacrificed themselves in war, Bush heals his own guilt. Bush is guilty of crimes against decency, by ordering a war – he is a warmonger. However, wounded veterans have a different perceived moral relationship to war. War provides veterans with honor through valor. Their sacrifices are interpreted as a form of service to the greater society. By connecting to an identity that valorizes war, Bush can reframe the relationship of his own identity to war.

Starting a war made Bush into a monster, so he seeks to heal his conscience by surrounding himself with those his war has made into heroes.

It’s pathetic that a man who held as much power as George W. Bush would attempt to free ride off of the moral status of those his wars has harmed, all to make himself feel a little better about himself. Showing some love to a few veterans couldn’t hardly make up for the pain Bush caused. Yet, all that matters in this case is Bush’s own sense of identity in the context of his own moral values. Evil doesn’t usually take the form of a comic book villain. A person can have a sense of decency, a moral compass, commit acts of compassion, possess empathy, and still be evil. To diagnose Bush’s evil, one has to first examine the history of his moral self-identity.

During the campaign for the 2000 Presidential Election, the Washington Post ran an article exploring Bush’s youth, his past and his values. George W. Bush’s simple and idealistic view of his own father, George Herbert Walker, seems to have been the anchor of his worldview.

“Today, of course, Bush has embarked on trying to duplicate his father’s greatest accomplishment – becoming president of the United States. Relationships between fathers and sons are never simple, but the close parallels between their two careers, Bush’s fierce loyalty to his father and his thin skin whenever his father is criticized suggest something particularly complex.”

Bush 41 was a paragon of moral rectitude to 43. 43’s sense of right and wrong was entirely received from his father, with very little personal effort devoted to developing his own independent view of the world.

“One of the things that Bush often talked about was his family, especially his father. Several of the Bonesmen said Bush described him in ‘almost God-like’ terms.

“‘I can remember one instance of him using his Dad as an example of resilience, saying my father had a great disappointment in not winning the Senate seat, but this is what you do, you bounce back. So you’re down, you just get back up. His attitude was you gave it your best shot. And he used his dad to show this,’ recalled Robert McCallum, now an Atlanta lawyer.”

Even Bush Sr.’s position on war was uncontroversial, simply correct to Jr.

“‘He believed that his father’s position was correct – we’re involved, so we should support the national effort rather than protest it,’ recalled Robert J. Dieter, a Yale roommate for four years who is now a clinical professor of law at the University of Colorado.”

George W. Bush was a social creature, but he didn’t seem to be a boundary pusher. His time at Andover private school showed him to be extroverted.

“Within months of his arrival, Bush was seen as a campus mover, not on the strength his intellect or his athletic achievements, but by sheer force of personality. Bush was nicknamed ‘Lip’ because he had an opinion on everything – and sometimes a tongue sharper than necessary.”

At Yale, he partied, but not too hard.

“‘George was a fraternity guy, but he wasn’t Belushi in ‘Animal House,’’ recalled Calvin Hill, who was in DKE with Bush and went on to play professional football. ‘He went through that stage in his life with a lot of joy, but I don’t remember George as a chronic drunk. He was a good-time guy. But he wasn’t the guy hugging the commode at the end of the day.’”

Bush was known to think of others, and act according to an internal sense of dignity.

“Like his father, Bush could display good breeding along with his rough Texas edges. Several former classmates recall him going door to door with a sympathy card for a classmate from the West Indies – one of the few blacks on campus – who had lost his mother. Another classmate who hailed from a public school said he was struck by Bush’s efforts to reach out beyond his social circle.”

Bush, a famous Skull and Bones member, was a joiner.

“‘George moved seamlessly among all the different groups,’ recalled Ken Cohen, today a dentist in Georgia. At the same time, Cohen noted, ‘he was a Bush and he had a sense of who he was … his family tradition. He was not a rebel.’”

During the chaotic years of the Vietnam War protests, Bush seemed unphased. His attitude was conventional and maybe even disinterested.

“In a recent interview, Bush said he has no recollection of any anti-war activity on campus during his undergraduate years – an extraordinary statement considering that [Reverend] Coffin was by then a leader of the national anti-war movement and was arrested for aiding and abetting draft resistance during Bush’s senior year.”

Altogether, the portrait of George W. Bush painted by his history is very clear. He was a relatively simple man, uninterested in the depths of political thought. He respected his father and upheld him as the quintessential example of what respectable thought and behavior looked like, but he himself never deeply considered what that meant. He was a social guy, a clear extrovert, but hardly a remarkable social presence.

Bush was a boring guy. Friendly, social, possessing a mild sense of dignity, but ultimately having a forgettable character. He held a belief that morality and respectability were important, because of his father, but he never deeply examined the question beyond this conviction.

As a regular man, Bush was not a monster, but neither was he a giant. He was kind of a chump, a man who does have a conscience, but one about which nothing special can be said. He took all of his moral cues from his social superiors. Bush is a lot like Adolf Eichmann.

Eichmann was described as a profoundly average man of profoundly average intelligence. His intellectual conception of the world relied on clichés and official bromides. He deferred his moral thinking in all things to the system and his superiors. He had no particular interest in these questions himself and no real ability to generate his own personal insights about them. He was a joiner and liked to belong to groups where others could feed him a sense of identity and meaning. When he noticed his social betters endorsing seemingly evil plans, he consoled himself that as a lesser man this surely absolved him personally of any guilt. Consequently, he hardly had any guilt. Eichmann even bragged about what he did, oversold his own role, valuing notoriety and his sense of belonging — to Nazi social circles which no longer existed. He was able to live in the moral worldview of those he admired, unwilling to exercise any meaningful personal conscientiousness. He believed that conceding moral responsibility to others was a good enough excuse to absolve himself of personal moral accountability.

George W. Bush does possess a sense of guilt, or at least a little regret. He has at least some moral injury and seems to seek to heal it. As a simple person, his paintings and meetings with soldiers seem sufficient as therapy. Bush’s moral worldview permits him to feel guilt, just not in proportion to the great evil he has perpetrated. Bush’s evil lies with the fact that he is a man who is capable of guilt and regret, who is not a psychopath, but who is simultaneously able to remain completely unconcerned or uninterested in the trauma his choices have caused in millions of innocent lives.

Bush’s guilt recalls the fictional Colonel in Apocalypse Now who burned down a village in order to go surfing. Despite the monstrosity of the act, this colonel goes out of his way to provide water and empathetic comfort to a mortally wounded Viet Cong soldier. While the Colonel here is no Eichmann level mental midget, the literary metaphor refers to selective morality driven by contrived moral self-identity. It is an absurdist take on evil, but banal evil is somewhat absurd.

Bush’s evil is not the product of a person with a wicked heart. Rather, like Eichmann, Bush’s evil is a product of his stupidity. As a profoundly average man, a joiner who never questions much and concedes all moral and intellectual accountability to his social superiors, Bush simply allowed evil to happen. He is accountable for this, he is deeply guilty. However, his moral self-identity will never process that guilt. He is capable of understanding that his war has harmed brave soldiers whose lives he values, but because the world of his social and intellectual superiors – his father, the writers at National Review – does not care about Iraqi lives, neither does Bush. Make no mistake, this is profoundly evil, a profound moral lapse. Yet, the cause is Bush’s profoundly average nature.

Bush is worse than a monster, he is middling.

Altogether, George W. Bush’s conscience stands as a refutation of the Great Man or chieftain theory of national leadership. Conscience is a powerful force within humans. However, conscience is not built to bear the guilt of a nation. Conscience doesn’t process the magnitude of suffering caused by war. There’s a reason why it is said that one death is a tragedy, but one million deaths is a statistic.

Gut instinct, the heart and the individual conscience alone are not sufficient tools to evaluate the propriety of a given war. Humans are not qualified to make moral judgments of this magnitude. It’s making Sophie’s Choice a million times over for people we’ll never know. It is above our pay grade.

Instead, we humans should seek to avoid war, and pour our wealth and energy into actions which serve as alternatives to war. We should never trust human authority figures to have the moral capacity to make reasonable, good judgments about when to go to war or not.

In my opinion, Eichmann’s banal evil is actually a prototype for all evil. Men like Eichmann and Bush exemplify evil in its purest form. Humans are moral beings, and the concession of moral responsibility to others is the greatest form of surrender of which a human soul is capable. The social superiors who created the monstrous policy in which Bush and Eichmann merely operated — they may be smarter, more psychopathic — nevertheless are guilty of the same banality. They all hold a middling moral self-identity, and their moral world view is held deliberately narrow.

Cheney, Rumsfeld, Wolfowitz all. They all have a little Bush in them. Joiners, team members. The idea that sweet cool ninja spec-ops teams will solve world social problems is stupidity. The idea that you can start a little war, make some oil bucks in Iraq, then just move on is willful ignorance of the condition of and dynamics affecting other people. Thinking that a mere purple-fingered election will make immediate, deep changes to a centuries-old culture — more stupidity, on its face!

I’d be inclined to think that the truly wicked — the real psychopaths — tend to fit into the world with the rest of us much better than the idiots. They’re usually smart enough to know the limits, to understand that you have to pretend to be good around most people most of the time to get by in life. This type will order quiet assassinations, wipe villages off of maps in ways such that no one would notice. They’re the types that quietly execute the Salvador Option, and for better or worse restore stable conditions without history noticing. They’re evil too, they’re insidious, but their impact is less.

The truly evil who kill millions are always bungling idiots. Bush, the tantrum throwing Hitler types, the self-satisfied Roosevelts of history, joiner Truman, bone-brained Mao — all a bunch of morons, smug Idi Amins, who caused immense damage every time they were allowed to set policy direction in lieu of their subordinates. These subordinates, evil psychopaths like Curtis LeMay, or Reinhard Heydrich, they never started any wars, they didn’t appoint themselves, they didn’t carry out their own orders. Psychopathy limits itself. The stupid idiots, the banal evil, is what gives license to psychopathy.

Hitler was a self-aggrandizing, bungling chump. Eichmann was a midget of a man. Heydrich was evil, but his evil needed Hitler and Eichmann. LeMay bombed 1 million Japanese to death, but he needed Truman and the naïve, ever unrepentant farm-boy pilots on both sides of his psychopathy. Psychopathy is the seed of evil, but stupidity is the fertile ground in which it grows.

In Bush’s mind, he did the best job he could as president of an America which he views as an always good country, which has to fight wars sometimes. In his heart, he regrets that people he respects faced harm. He surrounds himself with people that are in all ways better than him, the soldiers he sacrificed. He feeds off of their valor to heal his moral injury. Yet, there seems to be very little concern in his heart for the true victims of his wars – the hundreds of thousands of dead innocents from foreign lands. Bush is an average man whose conscience is not equipped to conceive of that guilt. He is profoundly evil, because he is stupid.

The only justice Bush will ever face must come from the lessons we learn from him. One lesson stands out. Only idiots start wars. Another is that evil blossoms where conscience shrinks and shirks.