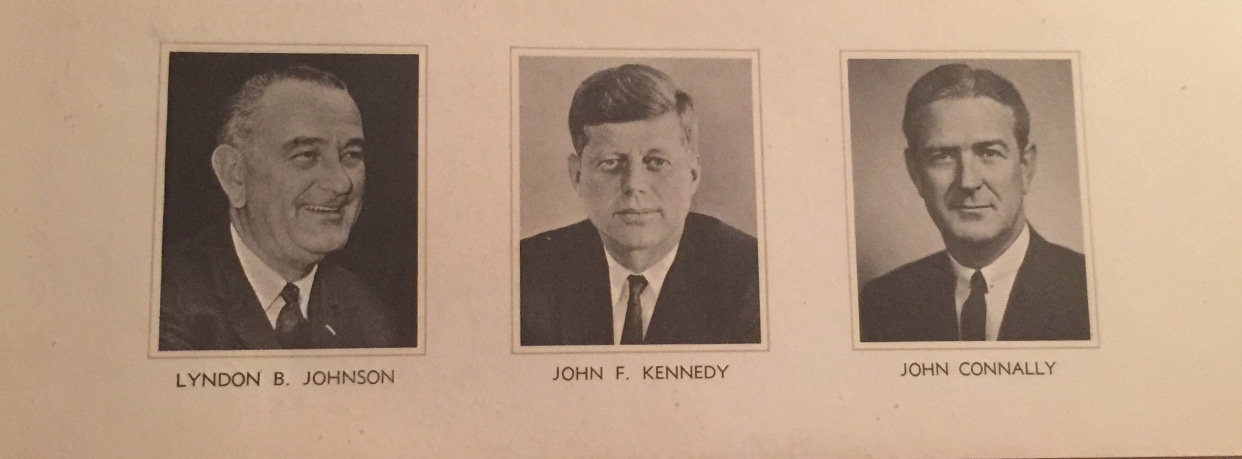

“Austin All Agog Over Kennedy Visit Friday” read the headline of the Austin American Statesman. The Texas capital was sparing no expense in welcoming the President of the United States. City schools were set to close early so that children could see the motorcade, and the excitement could be felt building in the weeks before.

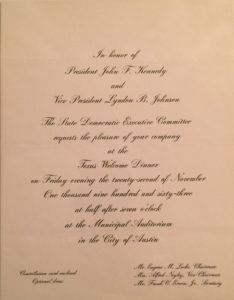

Preparations were in motion for a grand welcoming dinner at the city’s Municipal Auditorium. Hosted by the State Democratic Executive Committee, it would be the largest concentration of state and national leaders in the history of Texas.

Preparations were in motion for a grand welcoming dinner at the city’s Municipal Auditorium. Hosted by the State Democratic Executive Committee, it would be the largest concentration of state and national leaders in the history of Texas.

Nearly 2,500 people were expected to attend the $100-a-plate banquet dinner, whose purpose was to simultaneously fundraise for President Kennedy’s 1964 reelection campaign and heal the ongoing conservative-liberal split in the Texas Democratic Party.

That morning, the auditorium was decorated to befit a presidential visit, thousands of chairs were arranged, and caterers prepared the dinner, including “Texas-size” sirloin steaks.

But President John F. Kennedy would never arrive in Austin that evening of November 22, 1963. He would never make it out of Dallas. At 7:30pm that evening, when he should have been arriving at the gala to enthusiastic cheers, doctors at Bethesda Naval Hospital were removing bullet fragments from his brain.

In a recent interview on The Scott Horton Show, ret. CIA officer Ray McGovern mentioned what opened his eyes about the seminal event of that autumn day:

There is an excellent book that I’ll recommend to you, written by James Douglass, an eminent historian. It’s called JFK and the Unspeakable. It was released about 15 years ago [2008], completely suppressed in the press…It is, in my view, the Bible.

The book received similar praise from filmmaker Oliver Stone—whose promotion led to the book’s wide release despite a media blackout—and Robert F. Kennedy Jr., the president’s nephew who visited Dealey Plaza for the first time after reading. The book convinced Vietnam War whistleblower Daniel Ellsberg that a new federal investigation into the Kennedy assassination was urgently necessary.

Douglass’ tour de force is well-deserving of these commendations. Clocking in at 495 pages—including endnotes—it is a tome of information, the finest synthetization of primary and multi-decade secondary sources on the market.

Prior to researching the Kennedy assassination, author James Douglass spent his life as a Professor of Religion and a dedicated activist in the Catholic Worker Movement. This influence outlines the entire book, and even inspired the title. “The Unspeakable” was a term coined by the Catholic monk Thomas Merton, an adoptive son of Kentucky, and Douglass’ biggest theological influence. Merton sought to depict “an evil whose depth and deceit seemed to go beyond the capacity of words to describe,” including the carnage of the Vietnam War, the string of political assassinations in the 1960s, and the ever-looming threat of nuclear annihilation.

JFK and the Unspeakable serves as a masterpiece because of how Merton forms a narrative around the slain president. The reader is introduced to young Cold Warrior, who over a period of two years begins to have a redemptive shift towards peace—aroused by near cataclysmic events such as the Cuban Missile Crisis, and continual subversion by the National Security State.

From January 1961 to November 1963, Douglass tracks Kennedy’s growing disillusionment with the hawkish and militant perspective of his military command and intelligence agencies. Upon entering office, he’s introduced to a plan by CIA Director Allen Dulles for a preemptive nuclear strike on the Soviet Union scheduled for late 1963. Kennedy walked out on the meeting, telling Secretary of State Dean Dusk, “And we call ourselves the human race.”

After being cornered into the failed invasion of Cuba at the Bay of Pigs and firing Dulles, Kennedy declared his intention “to splinter the CIA in a thousand pieces and scatter it to the winds.” The president began continually curtailing the preferred policies of the National Security State, including by pursuing the creation of a neutral and independent Laos, sending military advisors into Vietnam instead of the requested combat units, and most importantly by rejecting the demands of his Joint Chiefs of Staff for a preemptive strike on Cuba during the missile crisis.

“If the situation continues much longer, the President is not sure that the military will not overthrow him and seize power,” Attorney General Robert Kennedy informed Soviet Ambassador Anatoly Dobrynin (as recollected by Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev in his memoirs).

Kennedy was met by constant disruption and sabotage by the National Security State he was meant to command. In Spring 1962, he orders Defense Secretary Robert McNamara to formalize a plan for a partial exit from Vietnam by the end of 1963; this order was backlogged by the bureaucracy for a year and was presented as a multi-year exit. The president was similarly ill-served by his last-minute appointment to the South Vietnam ambassadorship, Henry Cabot Lodge Jr.

Lodge declined to carry out continued negotiations with the Diem government to avoid a coup and delayed the transmission of information back to Washington. When South Vietnamese President Ngo Dinh Diem and his brother Nhu were assassinated on November 2, 1963, Kennedy was left “somber and shaken,” said Arthur Schlesinger, who “had not seen him so depressed since the Bay of Pigs.”

“I’ve got to do something about those bastards,” the President told Florida Senator George Smathers in the aftermath. “They should be stripped of their exorbitant power.”

You won’t find talk of ballistics or “magic bullets” in Douglass’ book. The events of November 22 take a backseat altogether; while he includes voluminous eyewitness accounts and a thorough walk through Oswald’s physical whereabouts, the author is less interested in the mechanics of the assassination than its context.

JFK and the Unspeakable is meant to help you understand why John F. Kennedy began a turn against the Cold War, and how the National Security State developed the motivation and determination to murder their Commander in Chief—not to calculate the mathematical trajectory of the Grassy Knoll.

More than a decade after its publication, James Douglass’ work stands as the pinnacle of Kennedy assassination texts, a required and laudable text for both laymen and enthusiasts alike.