The Frightened County is what Alan Renouf, one of Australia’s most prominent public servants, called Australia in his 1979 book of the same title. Renouf’s book is a delicate balance of criticizing past Australian alliances and military adventures while also embracing a future that would lead to much of the same. Renouf called for an independent Australia, but one that remains close to the United States. “She [Australia] fights for the same values as the U.S., that she is Western civilisation’s outpost there [Asia], that economically she is important to the West,” he wrote. Australia culturally and politically has never felt close to its geographical neighbors, only to its Anglo-American allies. Now it seems to be intimidated by all of them.

Recently, former Australian Prime Minister Paul Keating has condemned the AUKUS alliance between the United States, United Kingdom, and Australia. It is an alliance that has more than ever made Australia dependent and integrated into U.S. global hegemony. “We have been here before, Australia’s international interests subsumed by those of our Allies. Defence policy substituting for foreign policy,” Keating said last month.

The legacy media and Australian politicians have responded to Keating’s criticism. The usual charge is that he is out of line or acting irresponsible. In her piece “It’s Good to Be Mean to War Propagandists,” Caitlin Johnstone highlights the “ghouls” response in detail.

Australia is an insecure nation. It always has been. Federation in 1901 was as much about defense as it was any other perceived benefit of unifying the colonies into one commonwealth. From the beginning, the Australian military helped the British defeat Boers in South Africa and act as a barrier against the “Yellow peril” to the north. In the nineteenth century, the Australian colonies built numerous forts along its coastline in case of Russian invasion. In 1905, the Japanese defeated the Russian Empire, and to many Australian and Western observers, the defeat of a “mostly” European power at the hands of an Asian one was frightening. Add constant fears that the Irish populace may be rife with Fenians, that migrant anarchists may infect the white Christian populace, or concerns about the Chinese and the reduction of the Aboriginal “pest,” and you have the foundations of Australia.

Modern Australia celebrates multiculturalism and is full of diverse individuals, though in terms of policy—especially foreign—it acts in the same singular terms as it has in the past. The instincts remain. Even before the 1901 Federation, Australia had laws that would lead to the “White Australia Policy,” a fear that “Europeanism” would be either bred out by the “impure” or that in time a great “yellow” hoard would overrun the continent. Australia retained this white policy into the 1940s. The Boxer Rebellion in China at the turn of the century only instilled the fears of an uncontrollable and violent spirit of “Orientals” defying European mastery. Australia even sent a military contingent to help quell the rebellion.

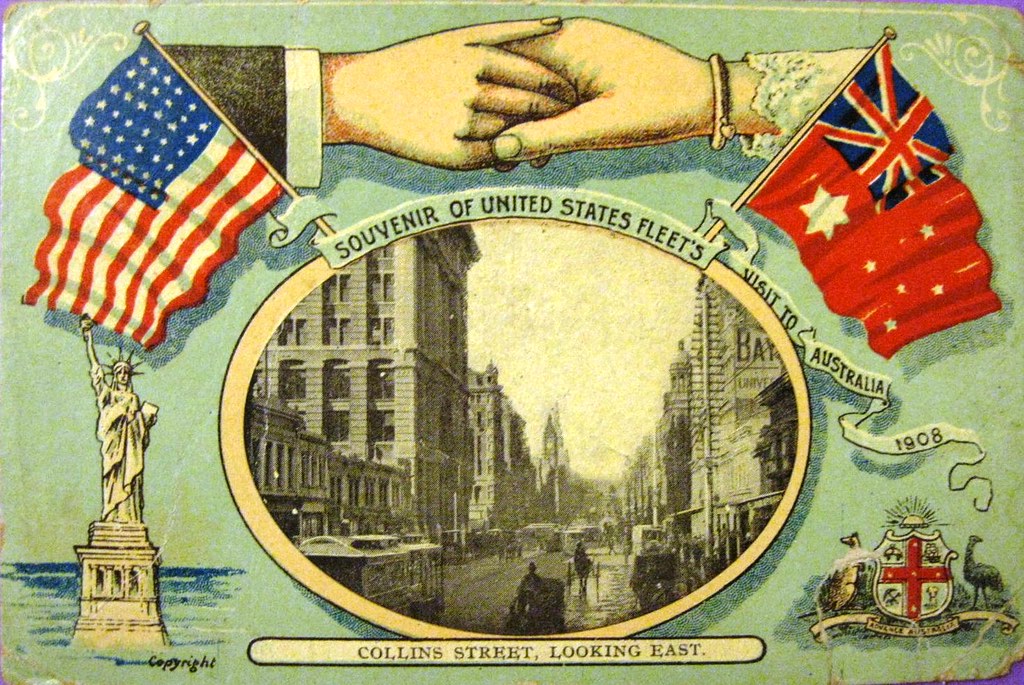

In August 1908, the United States’ “Great White Fleet” of mostly obsolete, white painted warships visited Sydney and Melbourne as part of a two year voyage across the world. It was President Theodore Roosevelt’s symbolic exercise of projecting American power. The Fleet was welcomed in Australia, the Yanks were seen as friends, their presence an assurance for the Australian public and political class that another powerful military ally existed to promote Western values in the East.

One of the many tasks for the American crew was to record strategic information on Australia and New Zealand, drafting up maps and gathering intelligence in case the United States should ever need to invade and conquer the land down under. Naive to this intention, the mob of excited Aussies cheered the foreign fleet on—they were, after all, white.

Australia would volunteer a generation of young men to fight for empire in the First World War. A new Pacific ally had been recruited to help secure the region while British and Australian vessels were required elsewhere. The Japanese Navy protected Australia during the war, securing supplies and safeguarding the coastline. Much of the Australian public back home were kept ignorant about the friendly Japanese Navy protecting them.

Another world war would come and Australia reenlisted as a loyal member of the British Empire. Australia felt isolated, with many of its fighting age men deployed far away fighting for the home island. When Japan entered the war as an enemy, the British government was reluctant to release Australian forces for the protection of their homeland, and instead sent many of them to suffer in blunders. In 1942, the Australian government had requested from London fighter planes to defend Australia but were denied. Canberra also wanted its fighting men to return to Australia, but British masters decided they would be best used elsewhere. Many Aussie soldiers were killed or captured in Greece, Singapore, and North Africa rather than sent home to defend Australia.

Once the United States entered the war, the situation in the Pacific was dire following Generalissimo Douglas MacArthur’s retreat from the U.S. colony in the Philippines. Afterwards he set up his headquarters in Australia. The shift began from Australian dependence on Britain to dependence on the United States. MacArthur become a stand-in emperor of Australia, making decisions at times for both the local Australian government and its military. It was not below MacArthur to take credit for victories and blame Australians for his mishaps, or downplay any Australian involvement in battlefield success.

“What has been good for London or Washington has not necessarily been good for Australia. That should should have been starkly clear after the experience of 1942. There were lessons for Australia in the war. It is not to late to learn them.”- David Day, The Politics of War

In the atomic age following World War II, the British government used parts of Australia as testing zones for various weapons. Canberra knew little about the results or risks as Australian service personal and civilians were used in the tests. Australia was a utility for London to exploit, and Canberra’s fear of Soviet atom bombs falling from above led to British ones exploding in parts of Australia instead.

During the early Cold War Australia would balance its obligations of service as part of the British Empire with its need for a U.S. strategic “friendship.” Australia was a large advocate of the U.S.-led South East Asian Treaty Organisation and the security treaty between itself, the United States, and New Zealand. The Australian military contributed to the Korean, Malayan, and Vietnam Wars with eagerness and loyalty. Australian governments welcomed U.S. military operations in Asia. Experts in Canberra reasoned that such wars in Asia would act as both forward defense for Australia while simultaneously keeping a large U.S. presence in the region.

By the 1970s, the United States had set up strategic bases in Australia, from crucial satellite monitoring stations to what is today known as “Pine Gap.” Parts of Australia under control of the U.S. became off limits, the details of which remain unknown to current policy makers.

Pine Gap, North West Cape, and Nurrungar became key American assets, locations to spy on not just the Soviet Union but the world. These facilities are not just used to spy and coordinate U.S. operations, but are also landing sites for U.S. strategic bombers, some of which may be nuclear armed. For all the Australian public knows, Uncle sam could have in place strategic missile silos. Australia was and remains in the minds of U.S. war planners a crucial island on the other side of the world, and its military a subordinate component of their own interests.

In the early 1970s, Australian Prime Minister Gough Whitlam began to challenge U.S. dominance of Australian policy. By 1972, Australian soldiers left Vietnam and Whitlam became openly critical of continued U.S. bombings in South East Asia. He explored a policy of self-reliance. Australian-American relations became stressed, especially as discussions developed about Australia leaving the strategic partnership and shutting down such facilities as Pine Gap, a direct challenge to Washington’s interests. Both Whitlam and his deputy prime minister had publicly and privately threatened to shut down Pine Gap should arrangements not be favorable to Canberra.

In 1975, Whitlam was overthrown in a political coup. This sudden change of government had British and American fingerprints all over it. The opposition party was installed, the Pine Gap issue was buried, and relations between the United States and Australia returned to Washington’s favor. Details of the 1975 coup can be found in the John Pilger article “Coup that ended Australian Independence.”

Australia has since become a coup nation. Paul Keating himself became a beneficiary of such an overthrow when he replaced Prime Minister Bob Hawke in 1991.

The level of involvement from the United States in Australian leadership changes is often omitted or dismissed as partisan and public intrigue. It would be naive to assume that Washington is kept in the dark before these drastic changes occur, and it is very likely the high levels of the U.S. government knows in advance of the Australian public who the new leader will be.

The Australian military is ever more reliant on the United States, up to and including its peril. In the case of the Seasprite helicopter affair, when the Royal Australian Navy (RAN) sought a maritime helicopter, corruption and incompetence ensured that none landed in Australian Defense Force (ADF) service, but that tax dollars assuredly left the nation. It was one of many embarrassments that should have been a lesson rather than another example of ADF politically-inspired preference to U.S. weaponry. The M1 Abrams tank has since been used by the Australian Army, replacing the aging AS1 Leopard tanks. Use of the F-35 and F/A-18 ensure continued integration with Australia’s biggest ally, while also generating reliance and a client nation status. Now Australia will get expensive U.S. nuclear powered submarines, a deal that suits DC’s Pentagon just fine.

The United States still controls parts of Australia, and under the AUKUS agreement it looks to be the major factor in most strategic decisions related to Australian defense and foreign policy. To the United States, Australia is just a geographical asset, a place for its spy facilities, air bases, naval ports to station while a capable and professional miltiary is utilized to project power into the Pacific. In over one hundred years, Australia has remained a frightened nation, one that relies on outside empires. The need to stand on its own two feet has always been there, but the will hasn’t. Winning an America’s Cup Yacht race decades ago is not enough. Aussies need to start saying no to the Yanks and stand up for their own self interest rather than to Washington’s.

Despite welcoming the war against China, Australian trade and reputation in Asia continues to suffer. The terms of AUKUS don’t favor Australian citizens. Instead the agreement mandates who is friend and foe, what can be traded and with who. From Canberra it’s a continuance of nineteenth and twentieth century insecurities. Canberra wants to have the Yanks close to home because Washington is intimidating, but the unknown Asian frontier frightens them more. Canberra’s policies have embraced its allies but ensured it no longer has any real friends, an arrangement which won’t end well.

Australian governments are not victims of reckless foreign policy and military adventures, they are complicit. The United States and United Kingdom most certainly benefit and even aid these decisions, but it’s a continued desire from Canberra and the insecurity and arrogance of its experts and politicians who continue to embrace policies favoring Anglo-American dependency. The belief that security is found in the U.S. waging a real or cold war in the Asia-Pacific region is dangerous. Perhaps for some in Canberra the uncertainty of peace is a lonely place for a self-alienating Australia.