“If the people who started wars didn’t make them sacred, who would be foolish enough to fight?” said Rhett Butler, the savvy anti-hero in Gone with the Wind. Politicians, activist historians, and social justice warriors have awarded the American Civil War an ex post facto halo. But viewing the Civil War as another “Good War” encourages people to naively view military destruction as a tool for national uplift.

The latest canonization of the Civil War is based on a series of myths that endanger peace and freedom in our time. The first myth regarding the Civil War was that the United States government was entitled to kill the residents of any state that sought to exit the union.

The Constitution was silent on the right of secession. In 1814, northern states gathered in Hartford, Connecticut and seriously considering exiting the union (they were aggrieved by the War of 1812 and by the embargo on foreign trade President Jefferson imposed in 1807—one of his biggest blunders). If the northern states had seceded, southern states would likely have responded: “Good riddance!”

In 1860, the election of Abraham Lincoln as president spurred seven states to secede even before Lincoln took office. Massachusetts governor John Albion responded by declaring, “We must conquer the South.” Radical Republican Congressional leaders “unanimously agreed that the integrity of the Union should be preserved, though it cost a million lives,” the New York Times reported on Christmas Day 1860. Lincoln pledged to take whatever steps necessary to compel the southern states back into the union.

Most media accounts nowadays portray citizens in states that seceded as traitors or “anti-American.” But in early 1861, as historian Shelby Foote noted, “New Jersey was talking secession; so was California, which along with Oregon, was considering the establishment of a new Pacific nation; so, even was New York City, which beside being southern in sentiment would have much to gain from independence.” “The Union was not formed by force, nor can it be maintained by force,” as a Nashville newspaper editorial declared in late 1860.

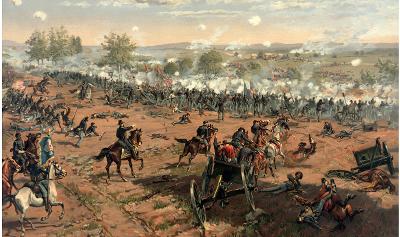

After the war started, opinion leaders in the north agreed that secession was a capital offense. In the thirteenth century, after Pope Innocent III authorized a crusade to exterminate heretics in southern France, a Papal Legate reputedly told the crusaders to “kill them all and let God sort them out.” Some northern generals took a similar attitude towards southern civilians. As Gen. William Sherman said in 1864, “There is a class of people—men, women, and children—who must be killed or banished before you can hope for peace and order.” The tactics followed by Union armies in Virginia, Georgia, and elsewhere late in the war sought to maximize destruction and suffering of the civilian population.

Was the U.S. Constitution akin to a barbarous marriage in which the husband is entitled to kill the wife if she files for divorce? If the Constitution had explicitly called for death sentences for residents of any state that sought to exit the union, few if any states would have joined after 1787.

The demonization of 1860s secession could undermine peaceful solutions to the growing political paralysis and hatred in contemporary America. If California goes even further leftward in the next few years and votes to secede, are other Americans entitled to kill all Californians and plunder their property? If New Mexico residents voted to join Mexico, do they all forfeit their lives? Do the people who castigate secession per se fail to appreciate the difference of results in Czechoslovakia compared to Bosnia?

The second myth of the Civil War was that much of the nation was so depraved that it needed to be brutally crushed. Pro-war Bostonians urged Governor Albion to “drive the ruffians into the Gulf of Mexico and give the country to the Negroes.” Many of the seven states that initially seceded were primarily concerned about preserving slavery at almost any cost. They were outliers at a time when humanitarian opinion in the United States and throughout the western world was becoming increasingly opposed to treating human beings as property.

Prior to the initiation of the military conflict, trade conflicts helped further alienate the nation. Southern states relied on agricultural exports and desired to purchase the best manufactured products at the lowest prices—which usually meant Europe. The Republican Party had speedily arisen in the prior years based in part on contributions from factory owners who sought captive customers south of the Mason-Dixon line for their often inferior products.

After seven southern states seceded, congressional Republicans rushed to enact a prohibitive tariff bill even before Lincoln took office. A New York Times editorial on February 14, 1861, warned that boosting the tariffs as high as 216 percent could drive the border states out of the Union: “One of the strongest arguments the [seceded states] could address to [border states] would be furnished by a highly protective tariff on the part of our Government, toward which they cherish the deepest aversion.” The Times condemned the bill as a “disastrous measure” that “alienates extensive sections of the country we seek to retain” and will “deal a deadly blow…at the measures now in progress to heal our political differences.” The Times’ astute arguments were ignored by Republicans determined to effectively blockade American ports to foreign goods.

The north won the Civil War in part because Abraham Lincoln was a smarter politician than Confederate President Jefferson Davis. After the first seven states seceded, a huge sticking point was the fate of Fort Sumter in which continued to be held by Union forces in the harbor of Charleston, South Carolina. Most of Lincoln’s cabinet and his military commander, General Winfield Scott, favored abandoning the fort to deny a pretext for war and allow tempers to cool on both sides. Confederate Secretary of State Robert Toombs warned President Davis not to attack: “The firing on that fort will inaugurate a civil war greater than any the world has yet seen…Mr. President, at this time it is suicide, murder, and you will lose us every friend in the North.”

Prior to the attack on Fort Sumter, Virginia supporters of the Union believed that Lincoln was serious when he seemed to offer them “a state for a fort“—that he would abandon Fort Sumter if Virginia would stay in the Union. But a day or two after delegates at a Virginia convention voted by an almost 2-to-1 margin not to secede, Lincoln approved sending the U.S. Navy to re-supply Sumter.

Lincoln knew that would spur Davis to order Gen. P.T. Beauregard to open fire. Lincoln quickly exploited the mass hysteria which the reckless Confederate attack provoked. Within days, northerners fervently rallied to support Lincoln and city lamp posts were adorned with nooses inscribed “Death to Traitors!” But Lincoln’s order to other states to provide troops to suppress the “rebellion” quickly doubled the size of the Confederacy east of the Mississippi as Virginia, Tennessee, North Carolina, and Arkansas seceded.

Lincoln believed that the northern states could speedily suppress the rebellion regardless of how many additional states exited the Union. After a victory at the battle of First Bull Run, some Confederate leaders foolishly believed their new nation was practically militarily invincible (Confederate generals such as Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson had no such illusions). The political arrogance and myopia on both sides of the Potomac multiplied the bloodshed.

The folly of vilifying much of the nation should give pause to contemporary activists who happily excoriate their political opponents in Red States, Blue States, or whatever.

The third deadly Civil War myth is that a war that ravaged the nation was necessary or the best way to liberate the oppressed. Slavery was a great evil that needed to be abolished. Nowadays, the Civil War is often defended as the cost of ending slavery. But in 1859, Abraham Lincoln said he was “quite sure [slavery] would not outlast the century.” Slavery ended almost every place else in the western hemisphere without a civil war.

In early 1861, Lincoln explicitly endorsed the Corwin Amendment, which would have prohibited the federal government from interfering with slavery within states where it was currently legal. That amendment was passed by Congress in early March 1861 and speedily ratified by legislatures in Ohio, Kentucky, Rhode Island, Maryland, and Illinois. But the ratification effort failed in large part due to the absence of states that had already seceded. In an August 1862 letter to newspaper publisher Horace Greeley, Lincoln declared, “My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union, and is not either to save or to destroy slavery. If I could save the Union without freeing any slave I would do it…”

In early 1862, Lincoln asked Congress “to consider a constitutional amendment that would guarantee compensated emancipation to any state, including those in rebellion, that would agree to abolish slavery gradually,” historian Thomas Fleming noted. If such an offer had been made prior to Fort Sumter, it might have helped keep the upper South states in the union. In late 1862, Lincoln issued his Emancipation Proclamation which provided a new justification for a war going worse than expected. Lincoln’s proclamation only applied to areas in rebellion—not to slave-owning areas that remained in the Union (such as Delaware, Maryland, Kentucky and Missouri). Lincoln’s proclamation “freed the slaves it couldn’t, and didn’t free those it could.”

In early 1865, Lincoln approved a joint congressional resolution for a constitutional amendment banning slavery—the most positive result of the war. The 13th Amendment also outlawed “involuntary servitude” but presidents and judges in the following century discovered a hidden codicil permitting servitude if politicians choose to conscript young men for foreign wars.

Though Lincoln is today hailed as a great liberator, Massachusetts abolitionist and anarchist Lysander Spooner declared in 1870, “All those cries of having ‘abolished slavery’…are all gross, shameless transparent cheats when uttered as justifications for the war.” Spooner wrote that slavery was abolished “not as an act of justice to the black man himself, but only ‘as a war measure,’ and because they wanted his assistance…in carrying on the war they had undertaken for maintaining and intensifying that that political, commercial, and industrial slavery,” subjugating the South for the profit of northern manufacturers and carpetbaggers.

At the end of the war, four million ex-slaves were largely left to fend for themselves. The horrific suffering of the former slaves was swept under the rug by historians for much of the twentieth century. However, as Professor Jim Downs noted in his 2012 book, Sick from Freedom, roughly 25 percent of freed slaves died or became gravely ill in the first years after the war. Ex-slaves suffered violence from the Ku Klux Klan, but even more suffered because they were liberated into an economic landscape that had been desolated by four years of increasingly destructive war. Sherman’s devastating march through Georgia and the Carolinas, for instance, resulted in “a large contraction in agricultural investment, farming asset prices, and manufacturing activity. Elements of the decline in agriculture persisted through 1920,” according to a 2018 National Bureau of Economic Research analysis. Harvests collapsed in the south during and after the Civil War; cotton output fell by half between 1860 and 1870. A 1997 analysis in the Journal of Economic History concluded that “the legacy of the Civil War was far more severe and long lasting than what has been previously supposed” for both blacks and whites, especially regarding illnesses such as hookworm spread in part by poverty.

If slavery could have been abolished without a war (as Lincoln forecast), the mortality rate of ex-slaves would have likely been far lower. Some zealots claim that the post-war mortality of ex-slaves is irrelevant to the Civil War as a glorious crusade. This is like President George W. Bush boasting about how the U.S. military “liberated” Iraqis but ignoring the horrendous carnage and civil war that followed the toppling of Saddam Hussein. President Barack Obama and Secretary of State Hillary Clinton were similarly nonchalant about the civil war that followed U.S. bombing to topple Muammar Gaddafi. Instead of democracy, Libya now has slave markets for black Africans operating openly. Obama remains revered regardless.

The Civil War should have taught Americans to be far more skeptical of saber-rattling politicians of any stripe. Both Lincoln and Davis effectively chose war to bolster their political support. Both of them claimed to be fighting for freedom and both quickly became dictators. Lincoln set precedents that have subverted in perpetuity the Constitution he claimed to adore. Politicians on both sides should have done far more to avoid the Civil War.

In the post-war era in the late 1800s, Republican politicians were notorious for invoking the “bloody shirt” of wounded veterans to demonize political opponents who did not tow the GOP line. Are we entering a new “Bloody Shirt” era with liberal and leftist invocations of the Civil War to justify further expanding government power and handouts?

The Civil War was one of the greatest tragedies of American history. Valorizing that war encourages people to believe that politicians can wave a magic wand, unleash vast carnage, and purported beneficiaries will live happily ever after. But permitting politicians to seize unlimited power to scourge evil is far more likely to result in tyranny than justice.