Friends of liberty inside and outside the Libertarian Party are waiting patiently—some passively—for three more weeks until the conclusion of the November presidential election. Not to find out whether Donald Trump or Joe Biden will come in first, but how many votes their own candidate will receive on the margin.

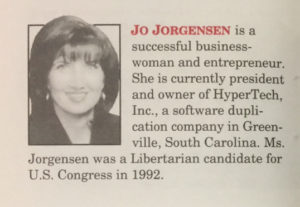

Jo Jorgensen, a businesswoman, university lecturer, and longtime party activist received the presidential nomination in May, with the (virtual) convention selecting activist and podcaster Spike Cohen as her running mate. Not long afterwards, the Jorgensen/Cohen ticket became the focal point of a bitter dispute within the liberty movement about messaging, with particular rancor towards their social media team.

While ascribing to nearly identical ideas, the rhetorical divide between libertarians seems almost insurmountable. Differences of opinion include what issues libertarians should prioritize, which demographics their message should be aimed at, what a unifying movement leader would look like, and whether political activism is even worth investment.

It would be instructive for libertarians to have a sense of how past candidates have portrayed themselves and sold their policies to voters. In its nearly fifty-year history, the Libertarian party has run presidential tickets from different factions and backgrounds, with different personalities, all while collecting different results. Finding what works, what’s unappealing, and what can be improved is necessary for future endeavors.

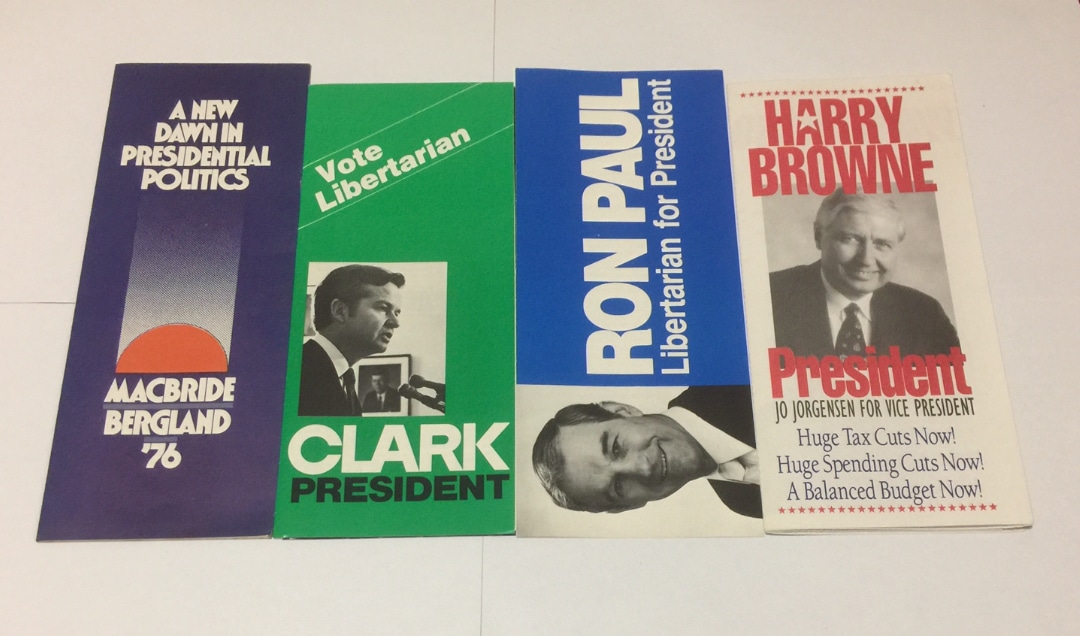

This article will focus on four of the Libertarian Party’s most prominent presidential campaigns—1976, 1980, 1988, 1996—comparing and contrasting the pamphlets that were meant introduce libertarianism to the voting public.

That faithless elector went on to be the party’s 1976 presidential nominee. Roger MacBride had formerly worked as a lawyer and, as the inheritor of the Laura Ingalls Wilder literary estate, co-created the NBC television series Little House on the Prairie. MacBride built his campaign around the phrase “a new dawn,” in which the Libertarian Party would break the country’s political duopoly and present Americans with a fresh direction. The brochure reads:

Who could deny that the politics of contemporary America should fade into the sunset and disappear forever? Most Americans, if we are to believe the public opinion polls, do desire a new dawn—a fresh approach to politics and a reappraisal of the appropriate role of government in a free society. The problem is, the candidates of the Republican and Democratic parties are from the old school of political wheeling and dealing. They sense that the public is ready for a new direction but they don’t know or care what that direction should be

MacBride’s brochure is heavy on rhetoric, candidate biography, and even includes a retelling of the party’s founding. What it lacks is policy proscriptions, with only a single page of bullet points quotes meant to inform the reader of where libertarians stand on the issues. With such limited space, it’s both curious but predictable that television producer MacBride would save special ire for the Federal Communications Commission, which he calls “one of the most dangerous agencies of government” for its censorship and intimidation of broadcasters. The FCC is one of the executive agencies MacBride promised to abolish, along with the FTC, ICC, and CAB, saying they “employ a virtual army of bureaucrats who are leeches on the productive sector of society.”

Despite the brevity, MacBride’s statement on U.S. foreign policy is worth quoting at length because of its foresight:

If I were elected President I’d retire Henry Kissinger as one of my first orders of business. The United States government has no right running around the world using tax dollars—the money you and I earn—to make ‘deals’ with foreign governments. The U.S. should stop intervening in other peoples’ affairs. I’m particularly concerned that the current Administration’s policy of involvement in the Middle East is going to lead to another Vietnam.

In November 1976, Roger MacBride won 172,000 votes, or one-fifth of one percent.

Where the MacBride brochure lacked on substance, Ed Clark’s indulges. A corporate lawyer, Clark gained appeal as a candidate after his 1978 campaign for California governor overperformed (he won almost five and a half percent). Riding high, he sailed to the presidential nomination in 1980.

While including photos of the candidate and a standard introduction, Clark’s brochure opens to reveal six pages of policy summations, making it by far the most detailed of the bunch. Clark elucidates his opinions on issues including, but not limited to, energy, unemployment, inflation, and crime, while even including separate subheads for civil liberties and the draft, along with foreign affairs and defense spending.

The Ed Clark campaign and its handlers earned the eternal enmity of Murray Rothbard when during a television interview, Clark used the phrase “low-tax liberalism” to explain libertarian ideology. This blunder has permanently attached the label of moderate or shallow to Clark’s run for office in the minds of many libertarians who proudly wear the moniker “radical.”

On that scale, Clark’s stated positions are a mixed bag; he goes all the way on some issues, but only partway on others. On one hand, Clark promised to abolish the newly formed Department of Energy, repeal all price controls, and eliminate the minimum wage. But on the other, while calling public education “a disgrace,” he goes no further than favoring tax credits for charter schools. Wonderfully, Clark refers to the draft as nothing more than “short-term slavery.” But while he favors reducing military expenditures, he gives no indication of how much.

One of the stances Clark was hit hardest on by other libertarians was taxes. In in the brochure’s introduction, taxes are the first issue mentioned, with Clark promising “the largest tax cut in American history.” It’s a phrase used repeatedly on other pages. To Rothbard and others, this fell too far short of calling for a full repeal of the income tax or destroying the IRS. In the same campaign, Ronald Reagan was making a similar promise, once again making Clark’s brand appeared watered down.

Like MacBride, the strength of Clark’s foreign policy stance and his recognition of blowback is worth quoting at length:

The United States supplies arms and aid to the world’s worst military despots. Indeed, in this century, we have supplied arms to both sides in seventeen different wars…The consequences and costs of this bankrupt foreign policy are becoming increasingly apparent, both at home and abroad. Our years of support for the despotic shah of Iran against the will of the Iranian people caused the Iranians to react violently against the United States. It is just one of many examples, from Vietnam to Nicaragua, of the failure of foreign adventurism. We must resolve now to avoid foreign crises in the future by staying out of the affairs of other countries.

On top of paper, the Clark campaign ran a litany of professionally produced, five-minute television ads. This surely benefited when come November, Ed Clark won 921,000 votes, or just over one percent. His 1980 campaign would hold the record on raw vote total and percentage until the Gary Johnson presidential runs of 2012 and 2016, respectively.

In 1988, Dr. Ron Paul was the most experienced presidential nominee in the Libertarian Party’s less than two-decade history. After a career in medicine, Paul had been elected to the U.S. House as a Republican four times, serving from 1976 to 1977 and 1979 to 1985. Despite having the most prominent career (both before and after his nomination), Paul has far and away the simplest brochure.

This appeal to the past is one of the hallmarks of the Paul brochure. While MacBride’s mentions the American Revolution twice, and Clark’s not at all, Paul references the Founding Fathers five times in a much shorter print.

Much of the substance in Paul’s brochure will discussed further on, but for now his skewering of U.S. foreign policy is once again worth quoting from:

The job of the U.S. government is to defend the people, property, and liberty of the United States. Period. It is not to run the world. It is not to fund wealthy clients like Germany and Japan. It is not to install and overthrow dictators in Central America. It is not to intervene on the side of totalitarian socialist Iraq and Big Oil in the Persian Gulf.

In November 1988 Ron Paul received 431,000 votes, or just under half a percent.

In his 1996 brochure, Harry Browne sells himself as much as the libertarian message. Taking an aside from explaining the budget to tell voters where they can buy his new book, the best-selling author and investment advisor was a natural marketer. In this instance, he does so by directly comparing himself to his Democrat and Republican opponents. In punchy bullet points, Browne presents what the major parties believe on spending, taxes, and social security, and follows with how he’s different.

The language is purposely dramatized to draw attention; balance the entire budget now (emphasis in original). And the issues are all geared towards matters that affect the daily lives of Americans. That specialization, while smart for voter targeting, leaves much to be desired in delivering the libertarian message. For instance, there is no mention of foreign policy, the only brochure to ignore the subject. The language, however, is the most accessible to the average person, using clear, simple direction to inform voter’s about Browne’s policies.

Harry Browne won 485,000 votes in 1996, or exactly half a percent. His performance was strong enough—the highest vote count since Ed Clark in 1980—and his personal appeal so universal that he was re-nominated by the Libertarian Party four years later.

Bringing all four brochures together, the first impression is their diverse color aesthetic. Each campaign appears to have chosen to lean on a single-color pallet; MacBride on a deep blue, almost purple; Clark on Green; Paul on light blue, and Browne on red. And like most political paper, a picture of the candidate included on the front, bar MacBride’s, which allotted for the “new dawn” imagery.

Both MacBride and Clark include a page of media mentions and favorable quotes from publications. They both even go so far as to recycle a quote from Nicholas von Hoffman in the Washington Post that he wrote in 1974. Paul has no media quotations but does include a list of organizations that had presented him with awards, including the Mises Institute. And Browne’s biography includes a list of the national television networks he had spoken on.

One of the pillars that unites all libertarians is opposition to the state’s monopoly on money production, and the devaluation of the U.S. dollar caused by the Federal Reserve. Both MacBride and Clark refer to the Fed’s monetary expansionism as “legalized counterfeiting,” and Clark provides a short explanation of how inflation benefits incumbent politicians and hurts workers. MacBride gives no further elaboration on a solution, and Clark calls for a return to “sound money,” but neither explicitly call for ending the Federal Reserve System.

Ron Paul does not mince words in his condemnation of the central bank. He promised to “protect the value of your money by restoring the gold standard and abolishing the Federal Reserve.” Whereas Harry Browne declines to mention monetary policy and sticks strictly to fiscal policy.

Something all four candidates do mention is the War on Drugs, although not necessarily in the same language. Roger MacBride takes a firm, but general stand against all victimless crime:

If there is no victim there can be no crime. This business of passing a law to prevent people from doing something simply because we think it’s morally wrong is nonsense. How we conduct ourselves is a moral question that can be answered by our own conscience.

Ed Clark likewise makes a broader, but more detailed statement about crime, and how it’s ill-handled by the police. He argues that drugs ought to be decriminalized, because “narcotics prohibition actually creates crime, just as alcohol prohibition created the gangster problem.” Both he and MacBride further argue that police should be made to focus on violent crimes “like rape, robbery and murder” (MacBride) instead of “wasting time and money on vice squads, drug busts and political spying” (Clark).

Ron Paul’s brochure, like Clark’s, uses the Prohibition era as a parallel, writing “In the 1920s, the unbelievable violation of our liberties called Prohibition strengthened public and private criminals at the people’s expense. The same is true of the War on Drugs.” This is included in a longer list of civil liberties violations, in which Paul mentions the invasion of the doctor-patient relationship, parental rights over children, and the state spying apparatus.

Like other issues, Harry Browne compares the Republican and Democratic Party’s insistence on “more federal powers, more police, more prosecutions, more prisons.” Whereas Browne would end the “insane” War on Drugs immediately:

This will take away the obscene criminal profits of drug pushers, break up street gangs, and make our cities safe again. Pardon non-violent drug offenders to make room in prisons for rapists and murderers who terrorize our citizens.

It is no secret that there are aspects of the liberty philosophy that are more difficult to pitch to non-libertarians than others. For instance, it is obligatory for a libertarian to believe in the right of association, that a person and property owner can associate or discriminate for any reason. Many libertarians prefer to ignore this philosophical cornerstone in ‘polite company,’ or other issues like state-mandated racial quotas and affirmative action. The closest any brochure comes to acknowledging this is MacBride’s, which obliquely references liberals “forcing an unending stream of ‘social engineering’ programs on us.” In all others, it is left unsaid.

Another dicey topic can be the welfare state, where even most conservative Republicans are happy to continue the social safety net instituted by Lyndon Johnson. Both MacBride and Clark chose to ignore the issue of welfare, while addressing nearly every other government program. In contrast, Ron Paul is very matter of fact, promising to eliminate “$500 billion in corporate welfare, social welfare, and foreign military welfare.” Instead, “churches and other private charities should be freed to care for the needy in a humane, non-governmental manner.”

The subject of welfare is where Harry Browne excels the most. In his brochure, Browne says the government’s “welfare system promotes dependency, irresponsibility, and poverty.” He further acknowledges without fanfare that gutting the federal budget and returning the government to its constitutional parameters “means ending all federal social programs.”

Social Security, the original bedrock of the modern welfare state and one of the third rails of American politics, is addressed specifically. Instead of inane reforms like adjusting the Consumer Price Index, Harry Browne would:

Sell off federal assets and use the proceeds to buy private retirement annuities for senior citizens who are dependent on Social Security—annuities from companies who keep their promises and never change the rules. Browne will end the 15% Social Security tax and leave Americans free to choose their own retirement.

The reason welfare can be a difficult topic for libertarians is because too often market alternatives can come across as unempathetic, or unrealistic, if not phrased right. Browne is able to perfectly encapsulate why abolishing the welfare state is not only financially necessary, but ethically the only possible solution:

You—not some bureaucrat—will decide who’s actually doing some good, who’s helping the needy become self-supporting, who’s earning your charity dollar—and how many charity dollars you’ll give them. So will your co-workers, neighbors, and other members of your community.

Charity, not welfare. Private compassion will succeed where government compulsion has failed.

On the other hand, taxes can be a libertarian’s favorite issue to discuss with the general public, and all the candidates jump at the opportunity. MacBride complains that “feudal serfs in the Middle Ages kept a higher percentage of their income than we Americans do today.” His simple fix is to “persistently seek to lower all taxes” because “they’re far too high—all of them.”

As previously mentioned, the key platform plank of Ed Clark’s campaign was the largest tax cut in American history. His brochure says he’ll explain the details of his tax program later on in the campaign, leaving the reader with the “economic fact of life” that allowing people to keep money they earn and “to save and to spend as they choose” leads to prosperity.

Ron Paul’s position is to not only lower taxes but abolish the income tax altogether. He has certain venom for the IRS collection agency in particular:

10,000 ravening, machine-gun-toting IRS agents oppress the people and eat out their substance. They have the license to confiscate your wealth, seize your bank accounts, and force you to incriminate yourself without due process of law.

Harry Browne shares that stance, and sought to it home in how uncompromising it was:

What will Harry Browne ‘replace’ the Income Tax with? A flat tax? No. A sales tax? No. A Value Added Tax? No. He’ll replace it with nothing.

Once again, Browne takes the time to explain the implications of this policy in a way to emotionally connect with voters and make them feel more comfortable about such a dramatic shift in government revenue:

Look at last year’s 1040 tax form. What would you do with the money the government took from you—money you earned—if it were yours to spend? Would you put your children in a private school that offers a better education and teaches your values? Would you put your money into savings or investments or perhaps use it to start that business you’ve always dreamed of? Would you move to a better home? Give more to your favorite charity or cause or church? Leaving all your earnings in your hands lets you make these choices for yourself, your family, and your community.

MacBride, Clark, Paul, and Browne possessed few ideological differences between each other. But in their presidential campaigns and voter outreach, they were very different in their choice of strategies. Analyzing their successes—and mistakes—is an important component of forming the best libertarian pitch going into 2021 and beyond.