While many Americans know that an Electoral College tie sends presidential and vice presidential elections into the House of Representatives and Senate, few realize there’s a constitutional crisis lurking in the incomplete rules for resolving such draws.

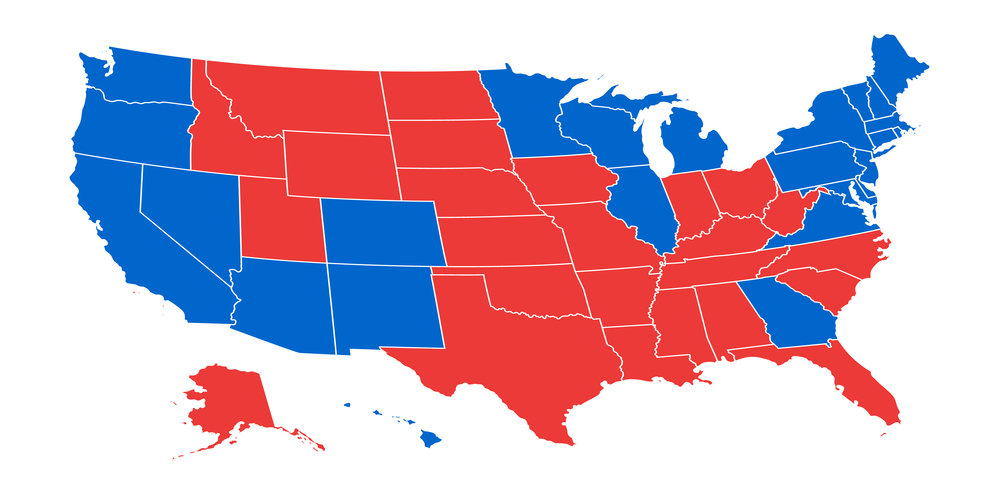

In 2024, scrutiny of these hidden dangers is more than a mere academic exercise, as there are plausible scenarios by which Joe Biden and Donald Trump could end up with 269 electoral votes apiece. One, for example, centers on Trump winning Nevada, Pennsylvania, Michigan and Wisconsin, and Biden winning Georgia, North Carolina and Arizona.

In the event neither candidate reaches the requisite 270 electoral votes, Americans would witness the first “contingent election” in 100 years. In accordance with the 12th Amendment, the president would be chosen by the House of Representatives, and the vice-president by the Senate. In both chambers, votes would be cast by the newly-elected Congress that first convenes in January.

That top-level description—which is about all you typically get from most media references to the possibility—is deceptively simplistic. In practice, a contingent election would be far messier than most Americans realize, with the potential for a deadlock that leaves the Oval Office unattended.

“Unsettled legal and procedural questions permeate nearly every aspect of the process,” wrote Beau Tremitiere and Aisha Woodward at Lawfare, “and in today’s political environment, high-stakes legal disputes and constitutional hardball would be inevitable.”

Before we look at the lurking risks to an orderly transfer of power, let’s quickly review some contingent-election basics.

How The House Chooses A President and the Senate Chooses a Vice President

In the House, presidential votes are cast not by individual representatives, but by state delegations, with each state having a single vote. The House chooses from the top three Electoral College vote-getters; of course, in most years, only the two major-party candidates receive any. Winning requires the votes of 26 states.

As of today, Republicans control 26 House delegations compared to the Democrats’ 22, while the North Carolina and Minnesota delegations are evenly split among the two parties. However, since the votes would be cast by the victors of the November election, the delegation-control math could be different when the 119th Congress is gaveled into existence at noon on Jan. 3.

If the House vote for president results in a tie, the state delegations keep on voting until there’s a winner. If that hasn’t happened by Inauguration Day—January 20, 2025—the new vice president becomes acting president until a candidate gets 26 votes in the House.

Things work a little differently in the Senate. Unlike the House’s state-delegation approach, individual senators cast their own vote for vice president. Rather than the top three electoral-vote finishers, senators pick among the top two. Counting independents who caucus with the Democrats, the Democrats currently control the Senate by a slim 51-49 margin, but face an uphill climb to retain a majority in January.

A Glaring Omission Could Leave Oval Office Empty

Here’s where we encounter a major gap in the contingent-election rules: While the 12th Amendment spells out what to do if the House is deadlocked on Inauguration Day, it fails to address the same possibility in the Senate.

The vice president is also president of the Senate. During ordinary business, vice presidents are summoned to cast tie-breaking votes. Some suggest that, since Kamala Harris would be vice president during the contingent election, she would simply cast a tie-breaking vote—for herself.

However, the 12th Amendment stipulates that “a majority of the whole number [of Senators] shall be necessary to make a choice [of vice president].” Some scholars argue that this rules out a tiebreaking vote being cast by the vice president, who is, strictly speaking, not a “senator.”

The most concerning scenario would arise if both the House and Senate are deadlocked on January 20. If that happens, some say the new president should be selected using the Presidential Succession Act of 1947. That’s the law that provides a line of succession that proceeds from vice president to speaker of the house, president pro tempore of the Senate, and then through the cabinet secretaries in order of their departments’ founding date, with State coming first.