The Amazon is burning.

This headline has crossed the world and received widespread media coverage. People everywhere have adhered to the broad claim and voiced their concerns about the planet’s future over social media. The most frantic ones marched in demonstrations carrying banners that blame agribusiness and capitalism for the catastrophe. They demanded urgent government action.

The truth is: hysteria will not help us, capitalism will.

Capitalism is NOT to be blamed… it is the KEY

We still do not know how the fires started – farmers, NGOs, the dry climate, deforestation are some of the explanations hinted at so far. But those explanations don’t matter now. The main questions are how to put these fires out and, especially, how to protect the forest for years to come.

So, who would be willing to do that? Who better than… CAPITALISTS! Individuals pursuing their own interests. Here’s the formula: if you want to protect something, make it valuable for someone. You do not need to beg people to not let their houses burn down, do you?

So, what we need to do is recognize what these fires are telling us: making nature “untouchable” by decree does not work. We need a new, more efficient model of preservation. We need practical measures to protect the Amazon.

How can we do that?

We must insert the Amazon into a FREE MARKET framework

Critics of capitalism always say that “money talks”. Yes, it does. And we need it to talk louder. We should let it talk in favor of preservation.

The better way to protect the Amazon is to find profitable, sustainable ways to use its natural resources. If we did that, the immediate consequence would be that destructive practices – which generally (but not exclusively) take place in black markets – would disappear or evolve into a sustainable growth model. If you are speculating that what is profitable is usually not sustainable, check the pop quiz below:

“What’s the difference between bald eagles, white rhinos, and giant pandas on one hand, versus talking parrots, dairy cows, and thoroughbred horses on the other? Answer 1: All of the former are endangered species, while the latter are in plentiful supply. Answer 2: It is illegal to trade in the former, while the latter are bought and sold in the open market”.

Dr. Robert P. Murphy points out that the hysterical warnings about natural resource depletion overlook the fact that within a free market framework, businesses find new ways and develop alternative technologies that conserve resources long-term, much better than any government regulations could. But, it happens only when it is profitable to do so.

So what kind of market can we expect for the Amazon? Ecotourism and biological research are just two initial examples. Want more? Take it easy! We’ve barely had the chance to think seriously about it. It is certain that, especially nowadays, there is a huge market for eco-friendly businesses. If you allow capitalists to use market forces to think of profitable solutions to these questions, you will see things happen.

Why CAN’T nature be a COMMODITY?

Environmentalists intend to make natural resources unsullied.

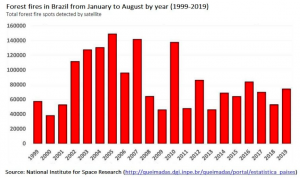

It is quite beautiful on paper, but the picture is not so attractive in reality. Regardless of ecological policies, tropical rainforests have been burning year by year (this year’s fires are not even the worst) and deforestation has long been a problem.

How long will nature suffer because of an abstract idea of integral protection?

By the way, the short-documentary “Save the Rhinos!” by ReasonTV illuminates this phenomenon. For 20 years, South Africa made it legal to own rhinos and sell their horns. Because of that, rhino farmers had a strong incentive to breed rhinos and protect them. What happened? The rhino population quadrupled. But then, in 2009, the activity was made illegal again. Why? Environmental groups screamed loudly that perceiving natural resources as commodities is fundamentally wrong – we should not farm animals in order to endlessly supply a bloodlust and thirst of people to consume wildlife products. What was the practical result? Poaching went up by 1000 percent in less than five years and now rhinos are at risk of being extinct within 10 years.

If it works like that for rhinos, why would it be different for the Amazon?

Is it a KIND of collective INSANITY?

“Insanity is doing the same thing over and over again expecting different results”. I do not know if this quote is truly by Albert Einstein. What I do know is environmentalists continue to ignore it. They insist that the solution for protecting the Amazon is surveillance and environmental regulation.

So, instead of trusting the free market, should we keep spending more public money on surveillance of miners, farmers and lumberjacks? Many South American countries (Brazil, Bolivia, Peru, Colombia, Venezuela, etc.) are poor! They hardly have money to invest in health, education, and infrastructure. This issue is a matter of budget (or lack thereof).

Ah, I got it! Rich countries should give money to these developing countries once they move to more restrictive environmental laws. First, more money will not necessarily change the situation. The Amazon is immense (2.7 million sq mi, while the US is 3.8 million sq mi and Europe is 3.9 million sq mi) – it would be impossible to design and pay for an oversight system that would operate across the entire forest. Second, if law could solve every problem, crime would not be a worldwide issue (there would be no drug dealers).

So what is the answer?

The answer lies in minding our own business

As I noted earlier, when people talk about nature, they always call for the government to do something. What they fail to realize is that governments have been active. The current model of preservation is based on two pillars: (1) Public Ownership (of national forests, parks, wildlife reserves, and so forth) and (2) Regulation. The problem is that these measures have proven to be highly ineffective.

It does not matter how many acres the government says are being protected or how many statutes have been enacted, environmental problems continue. Governments have tried vainly to protect nature through legal constraints. We should end where we ought to have begun: property rights.

Nowadays, it is not worth buying a piece of land in the Amazon region. Regulations do not allow you to profit from it (not even in sustainable ways). This is not good at all. In fact, this is an invitation for illegal activity: unauthorized lumbering and mining, predatory hunting and fishing, animal and plant trafficking.

In other words, the South American rainforest is the perfect portrait of what the economist Garrett Hardin called tragedy of commons – in theory, everyone wants to protect it but no one really does. The incentives favor irresponsible exploring, not careful protection. The Amazon is a nice house without doors or walls. Immoral people can enter and take valuable things for free.

Imagine if we changed that. If we had landowners care about their property in the Amazon, things would change. How? Simple! What if your neighbor came and tossed garbage on your lawn? You would not accept that, of course. But how many times have you passed by a wasteland and saw it covered with trash?

The same principle applies to the Amazon. What do you think would happen to a land lot in the Amazon, with operational real estate structure, if a landowner tried to use fire to prepare land for crops or to clear it for cattle? He would have to face annoyed neighbors. There would always be someone near to avoid this kind of activity.

What if the cause of the fires was something different, such as a dry climate. No problem! Let’s leave it to the capitalists to think of how to manage any of these challenges. Surely they will try hard to protect their OWN belongings. All they need is the proper incentives and property rights.

Let’s unlock the human creative potential to protect the Amazon.

Do people and governments still prefer inertia? Pay for that!

It is possible that the national government, foreign governments and the general population will insist that they want to prevent direct exploration into the Amazon. Although we may disagree, they are free to stand their ground (no pun intended). In fact, real estate rights are not incompatible with the classical preservation model (let’s call it holy inertness). It just requires someone to pay the owners to keep everything quiet – an agreement of non-exploration and duty to preserve nature.

Funding will not be a problem. There is currently an Amazon fund that has raised almost $ 1 billion since 2008 and whose slogan goes: “Brazil protects it. The world supports it. Everybody wins.” Germany and Norway are among the fund’s biggest supporters.

If sending money to the government and NGOs is a good idea, why can’t we send it to a landowner? What’s the difference? Oh, maybe there would be a significant change: sponsors would have to pay enough money to make inaction economically more profitable than the use of the land – holy inertness would be a product in the market with a price. But it is not that bad, is it?

South American people use to complain that Europeans destroyed their nature and now want countries to keep it at a high cost, non development. So, if rich countries pay a reasonable price (higher than the exploration one), this argument will no longer be available.

Another big advantage is that sponsors would not have a dozen NGOs wandering through the wilderness receiving tons of money (in 2018 NGOs working in the Amazon received $54 million) despite being unable to prevent fires, deforestation, and other illegal activities that cause problems. Instead, through free agreements, sponsors would hire an army of landowners eager to defend the forest and pursuing their own direct interests by guaranteeing the paycheck (fair price). As Adam Smith showed us long ago, “people respond to incentives”.

At the end of the day, this private system would be cheaper (including lower for supporters, since landowners would act under competition) and much more efficient. Besides, it would flow money into poor economies and create jobs by fostering new sectors and technologies related to environmental preservation.

In short: Landowners protect it. The world supports it. Now, everybody wins!

When EVERYONE owns something; NO ONE owns it

Who does the Amazon belong to? Every time I hear someone stating that the Amazon cannot be owned because it belongs to mankind, I remember Ludwig von Mises’s warning:

“If land is not owned by anybody, although legal formalism may call it public property, it is utilized without any regard to the disadvantages resulting. Those who are in a position to appropriate to themselves the returns — lumber and game of the forests, fish of the water areas, and mineral deposits of the subsoil — do not bother about the later effects of their mode of exploitation”.

When the government (“the public”) owns something, it is as if no one owns it.

Therefore, privatization is the solution.

In 2009, Brazil launched a land titles programme that distributed lots in the Amazon to small-scale farmers. What happened? Independent analysis based on satellite maps and government data showed that land where title deeds had been distributed had more forest left compared with territory lacking in titles. It’s a start.

Still, one might think that the insertion of biodiversity into a real estate system (a market mindset) is revolting. Well, if that is what it takes to save the forest, should we not embrace the idea?

What is worth more: the real nature or an ideology?

See, we are not assuming that a “Capitalist Amazon” would bring perfection (a Heaven on Earth). There would be distortions here and there, but we are convinced it would be a far more efficient way to protect nature than the current system.

And if, despite the evidence, some keep asserting that the free market is not an acceptable solution for the Amazon’s problems, then I am forced to say that their goal is not to protect nature, but to impose an ideology. The price of this ideology is watching the Amazon burn.

Jean Vilbert holds a Bachelors and a Masters of Law. He is currently a Judge, Writer and Professor in São Paulo, Brazil. You can reach him on Twitter @jean_vilbert