George Orwell wrote in 1945 that “the nationalist not only does not disapprove of atrocities committed by his own side, but he has a remarkable capacity for not even hearing about them.” This week is the 160th anniversary of one of the worst atrocities of the American Civil War, a barbarous episode that vanished long ago from history books. Union General Philip Sheridan laid waste to a hundred mile swath of the Shenandoah Valley, leaving vast numbers of women and children on the edge of starvation.

Before the summer of 1864, the Civil War was primarily fought on battlefields. After failing to decisively vanquish Confederate forces in pitched clashes, the Union leadership widened the war, trying to destroy the South’s economy—with the civilian population increasingly a target. William Tecumseh Sherman, the commander of the Union forces menacing Atlanta in 1864, telegrammed Washington saying that in the South, “There is a class of people men, women, and children, who must be killed or banished before you can hope for peace and order.”

On July 15, 1864, supreme Union commander Ulysses S. Grant signed an order that the Shenandoah Valley should be made into a “desert” and “all provisions and stock should be removed, and the people notified to move out.” His troops would “eat out Virginia clear and clean as far as they go, so that crows flying over it for the balance of the season will have to carry their provender with them.” In August 1864, Grant ordered Sheridan to “do all the damage to railroads and crops you can. If the war is to last another year, we want the Shenandoah Valley to remain a barren waste.” Sheridan set to the task with vehemence, declaring that “the people must be left nothing but their eyes to weep with over the war” and promised that, when he was finished, the valley “from Winchester to Staunton will have but little in it for man or beast.”

Because people lived in a state that had seceded from the Union, Sheridan acted as if they had automatically forfeited their property, if not their lives. Many who lived in the Shenandoah Valley, such as Mennonites, had opposed secession and refused to join the Confederate Army, but their property was also looted and burned.

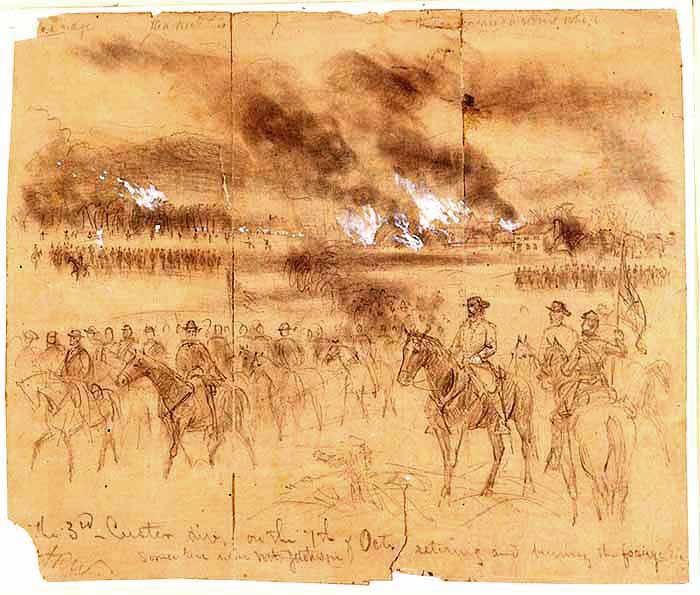

Stephen Starr, author of Union Cavalry in the Civil War, wrote, “The deliberate planned devastation of the Shenandoah Valley has deservedly ranked as one of the grimmest episodes of a sufficiently grim war. Unlike the haphazard destruction caused by Sherman’s bummers in Georgia, it was committed systematically, and by order.” Historian John Heatwole, author of The Burning: Sheridan’s Devastation of the Shenandoah Valley, recounted, “From a hill near Mt. Jackson Union cavalrymen counted 168 barns burning at one time. When it was all over Sheridan’s men had systematically destroyed around 1,400 barns, countless other farm structures, seventy mills, several factories, three iron furnaces, warehouses and railroad buildings, and hundreds of thousands of bushels of wheat, oats and corn, and crops standing in the fields. In Rockingham County alone, over 10,000 head of livestock were driven off.”

Some Union soldiers were aghast at their marching orders. A Pennsylvania cavalryman lamented at the end of the fiery spree, “We burnt some sixty houses and all most of the barns, hay, grain and corn in the shocks for fifty miles [south of] Strasburg. It was a hard-looking sight to see the women and children turned out of doors at this season of the year.” An Ohio major wrote in his diary that the burning “does not seem real soldierly work. We ought to enlist a force of scoundrels for such work.” A newspaper correspondent embedded with Sheridan’s army reported, “Hundreds of nearly starving people are going North not half the inhabitants of the valley can subsist on it in its present condition.” After one of Sheridan’s favorite aides was shot by Confederates, Sheridan ordered his troops to burn all houses within a five-mile radius. After many outlying houses had been torched, the small town at the center—Dayton—was spared after a federal officer disobeyed Sheridan’s order.

By the end of Sheridan’s campaign, the former “breadbasket of the Confederacy” could no longer even feed the women and children remaining there. An English traveler in 1865 “found the Valley standing empty as a moor.” Historian Walter Fleming, in his classic 1919 study The Sequel to Appomattox, quoted one bedeviled local farmer, “From Harpers Ferry to New Market, which is about eighty miles, the country was almost a desert…The barns were all burned; chimneys standing without houses, and houses standing without roof, or door, or window.” Historian Heatwole concluded, “The civilian population of the Valley was affected to a greater extent than was the populace of any other region during the war, including those in the path of Sherman’s infamous march to the sea in Georgia.” Unfortunately, given the chaos of the era at the end of the Civil War and in its immediate aftermath, there are no reliable statistics on the number of women, children, and other civilians who perished.

Some defenders of Union tactics insist there was no intent to harshly punish civilians. However, after three years of a bloody stalemate, the Lincoln administration had adapted a total-war mindset to scourge the South into submission. As Sheridan was finishing his fiery campaign, General Sherman wrote to Grant, “Until we can repopulate Georgia, it is useless to occupy it, but the utter destruction of its roads, houses and people will cripple their military resources.” President Abraham Lincoln congratulated both Sheridan and Sherman for campaigns that sowed devastation far and wide. But Lincoln’s cheerleading for collective punishment vanished from the history books thanks to his hypocritical call for “malice towards none” in his second inaugural address.

The carnage inflicted by Sheridan, Sherman, and other northern commanders made the South’s post-war recovery far slower and multiplied the misery of both white and black survivors. At the end of the war, four million ex-slaves were largely left to fend for themselves. The horrific suffering of the former slaves was swept under the rug by historians for much of the twentieth century. However, as Professor Jim Downs noted in his 2012 book, Sick from Freedom, roughly 25% of freed slaves died or became gravely ill in the first years after the war. Ex-slaves suffered violence from the Ku Klux Klan, but even more suffered because they were liberated into an economic landscape that had been desolated by four years of increasingly destructive war. Sherman’s devastating march through Georgia and the Carolinas, for instance, resulted in “a large contraction in agricultural investment, farming asset prices, and manufacturing activity. Elements of the decline in agriculture persisted through 1920,” according to a 2018 National Bureau of Economic Research analysis. Harvests collapsed in the south during and after the Civil War; cotton output fell by half between 1860 and 1870. A 1997 analysis in the Journal of Economic History concluded that “the legacy of the Civil War was far more severe and long lasting than what has been previously supposed” for both blacks and whites, especially regarding illnesses such as hookworm spread in part by poverty.

After the Civil War, politicians and many historians consecrated the conflict as a moral crusade and its sometimes-grisly tactics were consigned to oblivion. The habit of sweeping abusive policies under the rug also permeated post-Civil War policy toward the Indians (Sheridan famously declared, “The only good Indian is a dead Indian”) and the suppression of Filipino insurgents after the Spanish-American War. Later, historians would often ignore U.S. military tactics in World War II, Vietnam, and Iraq that resulted in massive civilian casualties.

The U.S. government’s targeting of civilians in the final campaigns of the Civil War signified a radical change in the relation between citizens and government that endured long after the South’s surrender at Appomattox. An 1875 article in the American Law Review noted, “The late war left the average American politician with a powerful desire to acquire property from other people without paying for it.” Ironically, a war that stemmed in large part from the blunders and follies of politicians on both sides of the Potomac resulted in a vast expansion of the political class’s presumption of power.

In the post-war era in the late 1800s, Republican politicians were notorious for invoking the “bloody shirt” of wounded veterans to demonize political opponents who did not tow the GOP line. After the September 11 terrorist attacks, America saw the same political vilification of anyone who dissented from the Bush administration’s wars. Will the same groveling reflex occur from any wars launched by the next president?

Since 1864, no prudent American should have expected this nation’s wars to have happy or uplifting endings. Unfortunately, as long as people rarely if ever hear of the atrocities their government commits, citizens will underestimate the odds that wars will spawn debacles and injustices that return to haunt us.