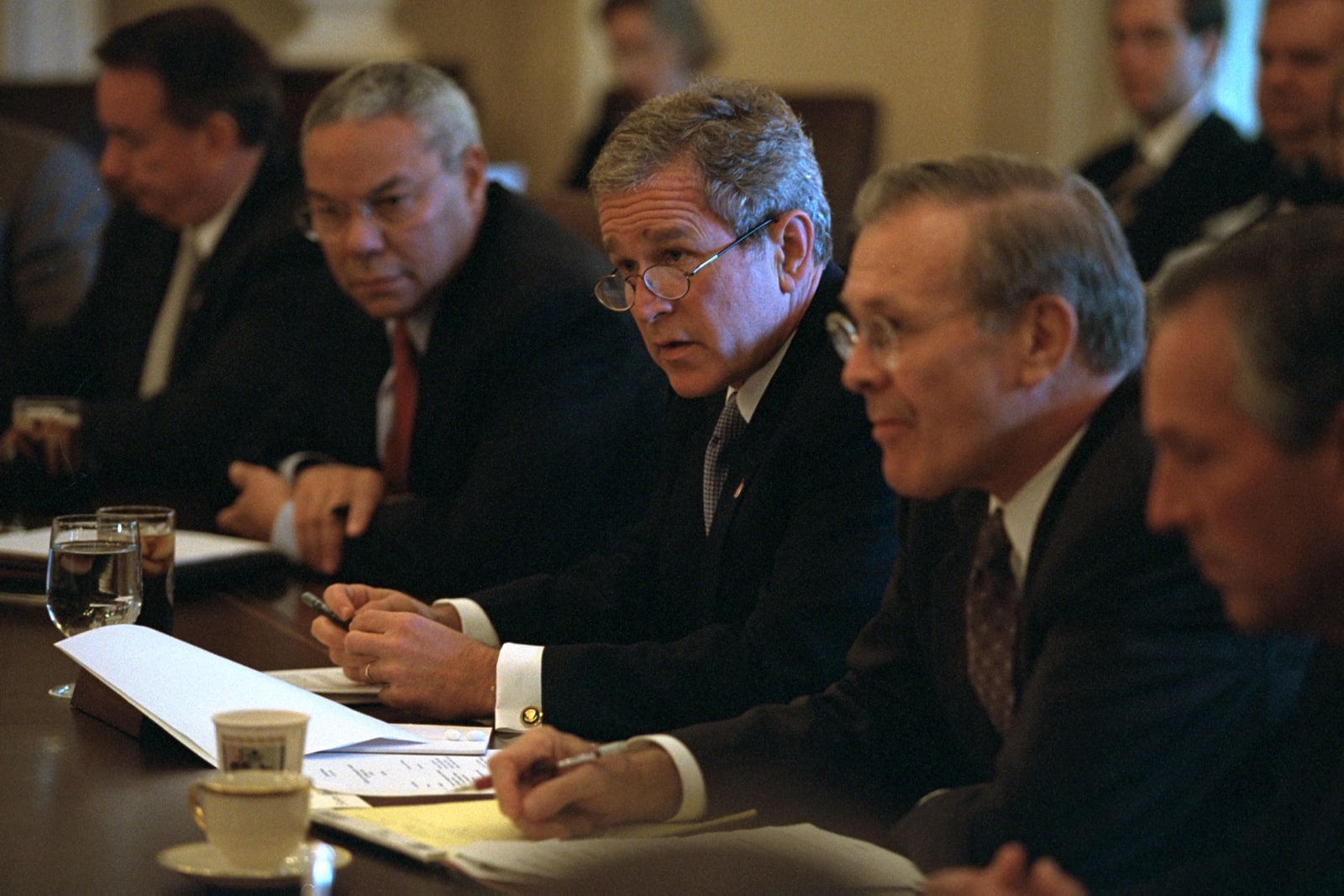

The top-ranking U.S. diplomat, Secretary of State Anthony Blinken, recently denounced Russian president Vladimir Putin as a war criminal, which has resulted in a marked uptick in the usage of that term throughout the media. Putin decided to invade Ukraine in February 2022 and has killed people in the process. That’s what happens when leaders decide to address conflict through the application of military force: people die. The U.S. government has needless to say killed many people in its military interventions abroad, most recently in the Middle East and Africa. Yet Americans are often hesitant to apply the label war criminal even to figures such as George W. Bush and Donald Rumsfeld, whose Global War on Terror has sowed massive destruction, death, and misery, adversely affecting millions of persons for more than twenty years.

Nor do people generally regard affable Barack Obama as a war criminal, despite the considerable harm to civilians unleashed by his ill-advised war on Libya. “Drone warrior” Obama also undertook a concerted campaign to kill rather than capture terrorist suspects in countries such as Pakistan and Yemen, with which the United States was not at war, and he armed radical Islamist rebel forces in Syria, which exacerbated the conflict already underway, resulting in the deaths of even more civilians. Obama’s material and logistical support for the Saudi war against the Houthis in Yemen gave rise to a full-fledged humanitarian crisis, with disease and starvation ravaging the population.

Moving a bit farther back in time, U.S. citizens and their sympathizers abroad typically do not affix the label war criminal to Bill Clinton either, despite the fact that his 1999 bombing of Kosovo appears to have been motivated in part to distract attention from his domestic scandal at the time. The moment Clinton began dropping bombs on Kosovo, the press, in a show of patriotic solidarity, abruptly switched its attention from the notorious “blue dress” to the war in progress. Throughout his presidency, Clinton not only bombed but also imposed severe sanctions on Iraq, as a result of which hundreds of thousands of civilians died of preventable diseases.

Despite knowing about at least some of the atrocities committed in their name by the U.S. government (torture, summary execution, maiming, the provision of weapons to murderers, sanctions preventing access to medication and food, etc.), many Americans have no difficulty identifying Vladimir Putin as a war criminal while simultaneously withholding that label from their own leaders. Viewed from a broader historical perspective, none of this may seem new. During wartime, much of the populace dutifully parrots pundits and politicians in denouncing the foreign leaders with whom they disagree as criminals, while supporting the military initiatives of their own leaders, no matter what they do. Is the use of the term of derogation war criminal, then, no more than a reflection of the tribe to which one subscribes?

All wars result in avoidable harms to innocent, nonthreatening people: death and maiming, the destruction of property, impoverishment, psychological trauma, and diminished quality of life for those lucky enough to survive. Given these harsh realities, some critics maintain that all war is immoral. But morality and legality are not one and the same, for crimes violate written laws. In the practical world of international politics, what counts as a criminal war has been delineated since 1945 by the Charter of the United Nations, which Putin defied in undertaking military action against Ukraine.

According to the U.N. Charter, to which Russia is a party, any national leader who wishes to initiate a war against another nation must first air his concerns at the United Nations in the form of a war resolution. The only exception admitted by the U.N. Charter is when an armed attack has occurred on the leader’s territory, in which case the people may defend themselves, on analogy to an individual who may defend himself against violent attack by another individual in a legitimate act of self defense. Barring that “self-defense” exception, the instigation of a war by a nation must garner the support of the U.N. Security Council, the permanent members of which have veto power over any substantive resolution. Putin knew, of course, that the United States would veto any Russian resolution for war against Ukraine and so did not bother to go to the United Nations at all.

Among the vociferous critics of Putin has been none other than President Joe Biden, who not only supported but in fact rallied for the 2003 invasion of Iraq, which was equally illegal, by the very same criterion which makes Putin’s invasion of Ukraine a criminal war, and by extension, Putin a war criminal. Indeed, Putin arguably followed the U.S. precedent and longstanding practice in “going it alone.” For the very same reason (the likely veto of any possible resolution) President Clinton decided to “go it alone” in choosing to bomb Kosovo in 1999, as did President George W. Bush when he ordered the invasion of Iraq in 2003. President Barack Obama took a slightly different tack in 2011, for he deceptively secured support at the United Nations for a no-fly zone in Libya but then proceeded to carry out a full-on aerial assault in that country over a period of several months, which culminated in the removal of Muammar Gaddafi from power and ultimately his murder by an angry mob.

We know that the 2003 invasion of Iraq was illegal according to the letter of the law not only because former U.N. Secretary General Kofi Annan plainly stated that it was, but also because the U.S. government drafted a war resolution only to withdraw it when it emerged that they did not have enough support to secure the needed U.N. approval. If U.S. leaders had believed that the invasion was completely legitimate according to the terms of the U.N. Charter, then they would have felt no need to draft a resolution in justifying it. Ex post facto, when it emerged that the alleged WMD serving as one of the primary pretexts for the war were nowhere to be found, the U.S. government claimed that the 2003 invasion of Iraq was simply a continuation of the 1991 Gulf War (which had received the support of the United Nations), or was justified because Saddam Hussein allegedly tried to assassinate George H.W. Bush in 1993, or because previous U.N. resolutions relating to the disarmament of Iraq and the elimination of its biological and chemical warfare capacity implied that military force would be permissible in the event of Saddam Hussein’s noncompliance. On the propaganda front, the administration also pumped through the media pretexts such as that the people of Iraq needed to be liberated from their ruthless dictator, and it was high time to allow democracy to flourish throughout the land.

People have been writing about war crimes for millennia, long before the establishment of the United Nations and the ICC (International Criminal Court). The framework proffered in the 1945 U.N. Charter derives from the classical just war tradition. By definition, a war criminal is someone who commits war crimes, but according to just war theory, there are two ways to become an unjust warrior: one is to wage an unjust war; the other is to conduct a war unjustly. These two forms of injustice are outlined in the jus ad bellum and jus in bello requirements on a just war, the interpretive fluidity of which has often been seized upon by political leaders intent on waging war. Such leaders use just war theory opportunistically as a template in developing pro-war propaganda. The aim of the drafters of the U.N. Charter was to rein in such bellicose tendencies and thereby avert tragic and massively destructive conflicts such as World Wars I and II, by requiring explicit and intersubjective agreement among nations before a war could be waged.

In the modern world, where communication between government administrators is always an alternative to the use of military force, the jus ad bellum requirement of “last resort” has become especially problematic, if not impossible to satisfy, much to the chagrin of war marketers. Some leaders flagrantly refuse to negotiate, as did President George H.W. Bush before launching Operation Desert Storm in 1991. By informing Saddam Hussein (in a letter) that “Nor will there by any negotiation. Principle cannot be compromised,” Bush Senior effectively proclaimed to the world that war had become the last resort. But this was only because the U.S. president himself refused to consider any nonmilitary means to resolve the conflict. Even more dramatically than all of the war criminals to follow in his footsteps, George H.W. Bush demonstrated that modern leaders decide to wage war and then, if pressed, with the aid of their public relations staff and media pundit propagandists, they interpret the tenets of just war theory so as to support their military intervention.

In drumming up support for the first U.S. war on Iraq, the Bush Senior administration deployed a variety of deceptive techniques, including a heartwrenching story about Kuwaiti babies being ripped from their incubators by Saddam Hussein’s henchmen. Despite being an utter fabrication, that story was instrumental in garnering international support for Bush Senior’s coveted military campaign. Given the mendacious means by which approval for the 1991 Gulf War was granted by the United Nations, it should come as no surprise that the war was also conducted criminally. Among other atrocities, Iraqi soldiers attempting to retreat were buried alive, and civilian structures such as water treatment facilities were destroyed. Strikingly, even the claims of U.S. soldiers themselves to have been severely harmed by exposure to chemical agents released into the atmosphere during the bombing of factories were denied for years by the very officials who sent them to fight.

Deception is a form of coercion, which implies that a leader who offers false pretexts to secure the approval of the U.N. Security Council, as did George H.W. Bush in 1991, is no less a criminal than a leader whose war abjectly violates the written letter of the law, as in the case of his son George W. Bush’s 2003 invasion of Iraq. Indeed, in predicting how leaders will conduct themselves during the prosecution of a war, there may be no more dependable indicator than how they went about garnering support for it. By now it is common knowledge that all of the proffered pretexts for the 2003 invasion of Iraq were bogus, from the nonexistent WMDs to the alleged collaboration between Saddam Hussein and Osama bin Laden. Given the many lies used to persuade politicians and pundits to support the invasion, no one should have been surprised when those who waged a criminal war proceeded to render and torture suspects, kill civilians at checkpoints, deploy white phosphorus and depleted uranium-tipped missiles, raze entire cities, and terrorize civilians with lethal drones.

Fast forward to 2022 with the invasion of Ukraine by the Russian military under Vladimir Putin. President Putin, like everyone, including all warmakers, has his own perspective on what he is doing. Following the example of all recent U.S. presidents in promoting their use of military force, Putin offered a “moral” pretext for his invasion of Ukraine. Among other things, he claimed to be protecting a portion of the Ukrainian people from Nazis. Comparing the various “humanitarian” pretexts offered by the U.S. government for its military interventions over the past three decades, the 1999 bombing of Kosovo probably comes closest to the template brandished by Putin in 2022.

In 1999, Serbian leader Slobodan Milosevic was painted by propagandists as “the new Hitler,” said to be slaughtering the ethnic Muslim population of Kosovars. The bombing campaign was rationalized by the need to stop Milosevic and protect civilians. Because Milosevic was on friendly terms with Russia, which held veto power at the U.N. Security Council, the Clinton administration waged its war, through NATO, without seeking the support of the United Nations. The crisis was depicted as a dire emergency situation requiring immediate action. The manner in which the intervention was conducted, however, with pilots flying high above the ground to avoid being shot down, thereby risking increased civilian casualties, belied those aims. More civilians were killed in the period after the bombing commenced than before, as Serbian soldiers were provoked to fight even more viciously in response to the aerial assault.

Putin’s anti-Nazi rhetoric notwithstanding, it is plausible that the Russian president’s primary concerns are geopolitical. Clearly troubled by the expansion of NATO to the east, right up to Russia’s border, Putin appears to want to secure his territory from any threats from the West. Given the 2014 coup in Ukraine, which was supported if not fully instigated by the U.S. government, Putin is no doubt concerned about the persistent hostility of NATO toward Russia, despite the fact that the U.S.S.R. no longer exists, and Russia is now a capitalist country. The conflict in Ukraine, as portrayed to television viewers, has offered nonstop confirmation of the prevailing picture of Putin as a ruthless dictator, which has been embraced by Western political elites since the 2016 presidential election, and was aggressively promoted by media outlets throughout the years of Russiagate during the Trump administration.

Putin is relentlessly denounced as a war criminal and the evil enemy by warmongers in the United States, even while knowing, as any rational person does, that the war must ultimately end at the negotiation table, given the reality of Russia’s arsenal of nuclear arms. When President Joe Biden angrily pronounced, “For God’s sake, this man [Putin] cannot remain in power,” he endangered not only Ukrainians but the very future of humanity by inching the conflict ever closer to a catastrophic nuclear confrontation. Arguably nothing could have been more reckless than for President Biden to announce to the world that the U.S. government’s intention was to depose Putin. Why? Because Putin has already seen, in recent history, what happened to Saddam Hussein and Muammar Gaddafi. If the Russian leader’s removal from power, indeed his very death, is in fact the foreign policy objective of the U.S. government, then Putin has no reason not to use nuclear weapons and take down as many people with him as possible.

While speaking to troops in Poland (a member of NATO), President Biden effectively informed them that they were being deployed to Ukraine, though earlier he had stated that the United States would not be entering into the conflict, because Ukraine was not a member of NATO and not a U.S. interest. Was Libya a member of NATO, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization? Of course not. But that did not stop President Obama from using NATO to wage a full-scale, regime-change military campaign in 2011. Biden’s staff immediately clarified that in fact U.S. soldiers were not being sent to Ukraine, thus sending a mixed and extremely confusing message about what the U.S. policy actually was.

To the dismay of the world community, Biden blundered yet again by setting up the operational equivalent to a red-line scenario, asserting that the U.S. military would retaliate “in kind,” should Putin opt to use chemical weapons. To some this may seem less like a red line than a potential tit-for-tat, but either way it is extremely dangerous. Under the ordinary understanding of what those words mean, Biden was stating that a chemical attack by Russia would be countered by a chemical attack by the United States. The hypothetical scenario limned by Biden was doubly dangerous, for it opened up the possibility for false flag attacks to be carried out by parties interested in drawing the United States into the conflict between Russia and Ukraine. That sort of provocation strategy has been seen in many contexts throughout history, including both Kosovo and Syria.

We already know from what happened recently in Syria, and many other places since 1945, that the provision of more weapons to a war zone exacerbates violent conflict. Whatever those who furnish military aid may intend, the weapons eventually find their way into the arms of persons willing to use them, for whatever their reasons happen to be. The more savage the war between Russia and Ukraine becomes, and the more civilian casualties reported by the media, the more likely it becomes that the conflict will escalate, drawing in other parties, including neighboring nations. Were NATO to get involved, that would be operationally equivalent to the United States’ overt entry into the war, given that NATO is dominated by the superpower.

When President Biden was asked to clarify all of his troubling remarks—that Putin had to be deposed, that U.S. soldiers were headed to Ukraine, and that the use of chemical weapons would be retaliated against (in kind!), Biden oscillated between reaffirming his statements and denying that he ever made them, leaving the entire world in the uncomfortable position of having to pin their hopes for a rational resolution to the conflict on Vladimir Putin himself, despite his having been relentlessly portrayed as the evil Manichean enemy, a ruthless dictator who is supposedly beyond the reach of reason. In reality, every military conflict ultimately ends, sooner or later, at the negotiating table. Refusal to negotiate evinces an utter insouciance toward the plight of people living under bombing and, in this case, given the danger of a nuclear war, the future of humanity itself.

The question now for U.S. government officials such as Secretary of State Blinken, who has shunned negotiation for months, is this: Why allow the destruction of any more human lives and property in Ukraine before agreeing to sit down and talk? Blinken may believe that dead Ukrainians are a small price to pay for U.S. foreign policy objectives, but the victims would surely disagree, as should the rest of the international community. It is unfortunate, to say the least, that so-called diplomats now regard politics as war by other means, having fully inverted the Clausewitzian formula. Nothing could be more obvious than that the longer the conflict is allowed to drag on, and prolonged through the injection of yet more weapons into the region, the more people, including Ukrainian civilians, will be killed. In other words, through postponing negotiation and sending tons of weapons to Ukraine, the U.S. government is using civilian victims as the means to its own foreign policy aims. Such a tactic is no less criminal than is punishing innocent people for the crimes of the guilty, the inevitable effect of economic sanctions against entire countries run by leaders who, in virtue of their position of power, retain privileged access to whatever they might need.

Biden’s debilitated mental state and inability to keep his story straight is the perfect metaphor for the attitude of Americans toward war criminals. They blithely ignore or brush aside the crimes committed by their own leaders while supporting policies which will intensify rather than resolve conflicts abroad. The term war criminal is at this point used as a rhetorical soundbite (à la just war), bandied about as a way of distracting attention from the speakers, who delusively imply that because they can identify war criminals, the label could not possibly apply to themselves.