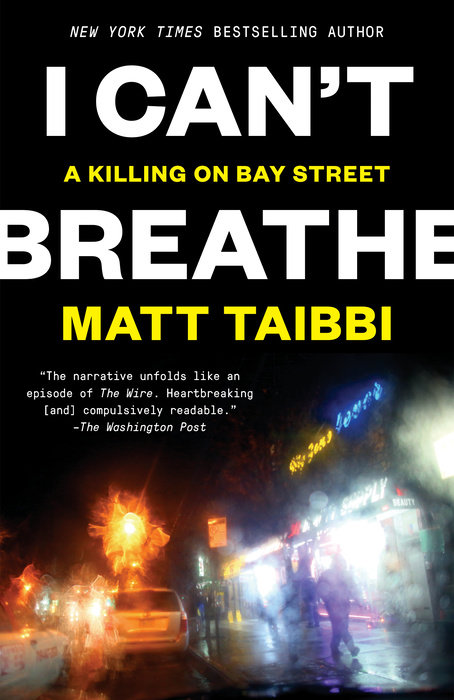

I Can’t Breathe: A Killing on Bay Street by Matt Taibbi (New York: Spiegel & Grau, 2017); 336 pages.

On the first day of law school, Yale Professor Stephen L. Carter walks into his contracts class with a message: “Every law is violent.” He then proceeds to tell his students that they should be willing to invoke the law only if they’re comfortable with the transgressor’s dying for breaking it. The students, he says, think he’s being a crank, but Carter reminds them that even a breach of contract is eventually enforced at the end of a gun. “[If] the breacher will not pay damages, the sheriff will sequester his house and goods,” Carter writes, “and if he resists the forced sale of his property, the sheriff might have to shoot him.”

Case in point: On July 17, 2014, 43-year-old Eric Garner, a father of six, died due to the unjustified actions of a police officer near the tip of New York City’s Staten Island. After breaking up a fight in a park across the street from where he sold “loosies,” or individual untaxed cigarettes, Garner was confronted by two police officers, Daniel Pantaleo and Justin Damico, who were there to arrest him for his illegal trade. There is one problem, though: No evidence has emerged that the officers saw him sell a cigarette. The officers didn’t care. They were arresting him. He was a nuisance and an eyesore in the gentrifying neighborhood.

“Every time you see me, you mess with me,” Garner said. “It stops today.” And it did. Pantaleo pounced on Garner and grabbed his right arm with both hands while Damico tried to grab his left arm. Garner resisted. During the scuffle, Pantaleo put Garner in a chokehold. “I can’t breathe,” Garner, clearly terrified, pleaded over and over again, in the infamous video shot by Ramsey Orta. He finally lost consciousness, the small officer’s arms around his neck. A store owner looked down at Garner, unconscious and handcuffed face down on the sidewalk outside his store, and asked another officer on the scene, “How come you’re not giving him CPR?” The cop replied, “He’s fine. He’s breathing.” Approximately an hour later, Eric Garner was pronounced dead.

Eric Garner

In a riveting, fast-paced piece of literary journalism, muckraking Rolling Stone journalist Matt Taibbi tells the story of how that fateful encounter on Bay Street unfolded through 13 characters, including Garner, who provide an intimate portrait not only of the larger-than-life man but of New York City’s Kafkaesque criminal justice system. Taibbi, however, isn’t content to just tell Garner’s story. He uses the case as a jumping-off point to examine New York City’s criminal justice system and the corruption that permeates it. What he describes is a libertarian’s nightmare of overzealous and unconstitutional policing pushed by city halls that want to appear tough on crime, even if that means harassing people — mostly black and brown — for victimless crimes. It is a deeply depressing and demoralizing piece of work.

To Taibbi’s credit, he doesn’t write around the flaws of Eric Garner, descending into a mawkish hagiography, but confronts them head on. This is wise, because the man leaps off the pages, a tragic figure, noble but weak, like most of us. It’s also the only way to understand how Garner found himself in a chokehold that day in July 2014.

Eric Garner was a convicted crack dealer who also did a spell in prison for assault. But after he got out of prison the second time, his children gave him an ultimatum: Give up drug dealing or we’re out of your life. Weeping, he promised. Garner got a job with the Parks Department. He earned a paltry $68 every two weeks, which couldn’t feed himself, much less his kids.

Garner quickly fell back into drug dealing and got pinched again in September 2007. What is alleged to have happened to him during that arrest provides context to why he resisted arrest that fateful day in 2014. The arresting officer placed him in handcuffs and then humiliated him by “digging his fingers in my rectum in the middle of the street,” Garner wrote in a civil-rights complaint. That was common, Taibbi finds. One officer recounts that another officer told him that the cops of the 52nd precinct would often strip-search people on the street. They even had a term for it: “socially raping.”

After Garner got out of jail, he started selling cartons of cigarettes and loosies on the streets, courtesy of Mayor Michael Bloomberg. 9/11 had caused a massive budget deficit, and Bloomberg had a nanny-state solution to get back in the black: jack up the cigarette tax from 8¢ to $1.50. Always the entrepreneur, Garner started bootlegging cigarettes, making hundreds of dollars a day in profit. Another upside to selling untaxed cigarettes was that getting caught meant being charged only with a misdemeanor and paying a fine.

Garner saw the arrests as the cost of doing business and the only way an ex-con like him could provide for his family. But things quickly turned. The sight of the obese disheveled black man standing on Bay Street for hours and hours on end every day constantly attracted police attention because of the latest craze in policing: “Broken Windows.”

Broken-windows policing

The policing tactic was the brainchild of George Kelling, a child-care counselor and probation officer turned criminologist. Working in juvenile detention settings during the early 1960s, the young man observed that visible disorder led the kids to act out. “Kelling believed,” Taibbi writes, “that kids could not get the help they needed while they were surrounded by chaos — they needed to experience at least a minimal level of violence-free order before they could benefit from any treatment.”

As the years passed, Kelling would apply his observations to the streets. In 1982, The Atlantic Monthly published the article “Broken Windows,” which clearly articulated Kelling’s theory and revolutionized urban policing in the decades after, especially in New York City. Kelling and his co-author, James Wilson, a Harvard professor of government, believed that visible disorder on city streets — loitering in front of stores, panhandling, vagrancy — sends a message to criminals and delinquents: Have at it; no one cares.

But if police could proactively enter bad neighborhoods and clean them up by cracking down on public drinking, vandalism, and other low-level crimes, police and law-abiding citizens would send another message to more serious criminals: Don’t try it here, or you’ll be sorry. By aggressively policing petty offenses, officers would deter more serious crimes from occurring. As Taibbi describes it, the essence of broken-windows policing is the belief that “police might have to be given expanded leeway to enforce the nebulous and unwritten concept of order.”

When the theory was put into practice, it quickly degenerated into police harassment of communities of color in a city divided by race. Kelling and Wilson, Taibbi notes, always understood that their theory could mutate into bigoted policing. In the Atlantic Monthly article they said as much, asking, “How do we ensure … that the police do not become the agents of neighborhood bigotry?” The answer was less than sufficient. “We can offer no wholly satisfactory answer to this important question,” they admitted. “We are not confident that there is a satisfactory answer except to hope that by their selection, training, and supervision, the police will be inculcated with a clear sense of the outer limit of their discretionary authority.”

As police flooded black and brown neighborhoods across the city, another revolution in policing occurred. In 1994, newly elected mayor Rudy Giuliani hired Bill Bratton as New York City’s top cop. Bratton was a believer in broken- windows policing, which he would meld with his own innovation, CompStat. Using the crime statistics the department collected, Bratton deployed his officers to high-crime locations to make stops. They called it “Stop, Question, Frisk.” Rather than waiting for crime to occur and responding, Bratton’s officers would take the fight to criminals.

In New York City, that meant that it was usually white cops who policed black and brown neighborhoods, stopping people for subjective reasons such as “inappropriate attire” and “furtive movement,” and tracking their stops on form UF-250. The forms were proof that the officers were doing their jobs, and their superiors pushed them to make as many 250 stops as possible, creating a positive feedback loop of unconstitutional policing. When experts analyzed the forms, something stood out. The essentially meaningless “furtive movement” was the reason for nearly 50 percent of the stops, and nearly 90 percent of people stopped were black or Hispanic.

During Ray Kelly’s tenure as police commissioner during the Bloomberg years, a black state senator testified that Kelly told him, writes Taibbi, that the NYPD’s goal “was to change the psyche of young black and Latino men by ‘instill[ing] fear in them that every time that they left their homes they could be targeted by police.’” The goal, according to police, was to get guns and drugs off the streets. It failed. According to an analysis of stop-and-frisk data by the New York Civil Liberties Union, guns were found less than 0.2 percent of the time, while nine out of ten New Yorkers stopped were released without being charged.

But the NYPD’s practices plunged black and Hispanic residents into a police state where they could be stopped and harassed on the whim of an officer’s suspicion or prejudice. This was the daily grind for Eric Garner and others like him, and it was done by design. One of the reasons the stop-and-frisk policy was found unconstitutional in 2013 was a police officer’s surreptitious recording of his superior. “This is about stopping the right people, the right place, the right location,” the deputy inspector, Christopher McCormack, said. The right people, according to McCormick, were “male blacks, fourteen to twenty, twenty-one.”

An unusual grand jury

Zero-tolerance policing naturally generated intense hatred and hostility toward police. Police responded likewise, almost always protected from punishment when they got violent. When police cross the line and rough up someone, Taibbi reports, the city automatically goes on offense to deter the victim from filing a civil-rights lawsuit.

Prosecutors pile on charges, hoping the victim will cop to a lesser charge, which will decrease the chances the civil-rights lawsuit will ever be filed. As Taibbi notes, civil lawyers generally wait until the charges are beaten to file suit against the city. Even if they do file suit, the plea deal makes it unlikely the victim of police abuse will win in court. The victim, after all, is a “criminal.”

Generally, prosecutors can go before a grand jury and get an indictment within an hour. In the Garner case, however, the adage about a prosecutor’s being able to convince a grand jury to indict a ham sandwich didn’t hold up. One reason might have been that this particular grand jury proceeding appeared more like a full-fledged trial, which determines whether or not a person is guilty of a crime, than a simple grand-jury proceeding, which determines whether there is sufficient evidence to warrant a formal accusation that a person has committed a crime.

In the Garner case, the grand jury convened by Dan Donovan, Staten Island’s Republican district attorney, sat for nine weeks and heard from 50 witnesses, 22 civilians, and a mix of 28 cops, emergency personnel, and doctors. All this was atypical, Taibbi stresses. “If you think a crime was committed (and by taking the case to a grand jury, Donovan was formally signaling that he believed one had taken place),” asks Taibbi, “why not just walk into any normal grand jury with Ramsey Orta’s video, call a few witnesses, and walk out with an indictment or two later?” In any event, by the end of this lengthy proceeding, the grand jury failed to return an indictment against Pantaleo.

Not only did the Garner family have to accept that there was no indictment, they would learn two and a half years after the grand jury decision, when Officer Pantaleo’s disciplinary record was leaked to the website ThinkProgress, that of 14 abuse allegations, four were substantiated, including a strip-search Pantaleo conducted in public. The city’s Civilian Complaint Review Board recommended that the NYPD punish all four substantiated complaints harshly. The department ignored the recommendation and decided Pantaleo only needed more training.

In other words, the department acted negligently and Garner paid the ultimate price. “ThinkProgress characterized Pantaleo’s record as a ‘chronic history’ of abuse cases that would put him ‘among the worst on the force,’” Taibbi writes. “The stats backed up their analysis. Only about 5 percent of police received eight or more complaints. Pantaleo had fourteen. And only about 2 percent had as many as two substantiated complaints, while Pantaleo had four.” Officer Daniel Pantaleo is currently still on the payroll of the NYPD, while Eric Garner is six feet below ground.

In the end, Taibbi’s I Can’t Breathe is a searing indictment of New York City’s criminal justice system and how it works like an “industrial production scheme,” where black and Latino males are the “raw materials.” Taibbi’s narrative is necessary reading for anyone who remains skeptical of this fact: Certain communities in America live under a police state that enforces the law, often unnecessary laws, harshly with little to no guilt about the consequences for individuals and community relations with the police. As Professor Carter tells his students: Every law is pregnant with violence. If the average citizen understood that, maybe Garner, and countless others, would be alive today.

This article was originally published in the December 2018 edition of Future of Freedom.