In the aftermath of World War II, U.S. policymakers felt they faced an increasingly dire situation in China. By late 1949, Mao Zedong’s Communist forces had decisively defeated Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalists (Kuomintang/KMT), pushing them off the mainland to Taiwan. In the mind of Dean Acheson, secretary of state under President Harry Truman, the collapse of the Nationalists raised pressing questions. Could Taiwan be held against a Communist invasion? And was Chiang Kai-shek the right leader for this task? Acheson’s initial plans, however fleeting, to replace Chiang underscore the uncertainty and improvisation that characterized U.S. strategy in the early Cold War, and the hubris of the policymakers in Washington, convinced of their right to run the world.

Chiang’s regime had long been viewed with skepticism by American officials, even during the wartime alliance against Japan. Rampant corruption, poor governance, and military failures left the KMT vulnerable to the Communist insurgency. By 1949, Acheson and many in the Truman administration believed that Chiang bore significant responsibility for the Nationalists’ defeat.

Acheson’s January 1950 white paper on China publicly declared that the United States had done all it could to support Chiang’s regime and absolved Washington of blame for his collapse. Privately, Acheson believed that continued support for Chiang could harm American credibility and that Taiwan’s future depended on new leadership. He and other officials entertained various proposals, including sidelining Chiang in favor of a more competent leader or placing Taiwan under an international trusteeship.

One idea floated within the State Department was to engineer a transition of power within the KMT, potentially elevating more reform-minded figures such as Sun Fo, the son of Sun Yat-sen. Other suggestions went further, advocating for the establishment of a coalition government that might include non-KMT factions to stabilize Taiwan’s governance and make it a stronger bulwark against communism.

Chiang was acutely aware of these discussions. In early 1950, he acted preemptively by arresting General Sun Li-jen, one of the most respected Nationalist military leaders. Often referred to as the “Rommel of the East,” Sun was widely admired in Washington for his competence and honesty, qualities that stood in stark contrast to the corruption and inefficiency of Chiang’s regime. Fearing that Sun was being groomed by the United States as a replacement, Chiang accused him of plotting a coup and placed him under house arrest, where he would remain for decades. This decisive move eliminated a potential rival and signaled Chiang’s refusal to cede power.

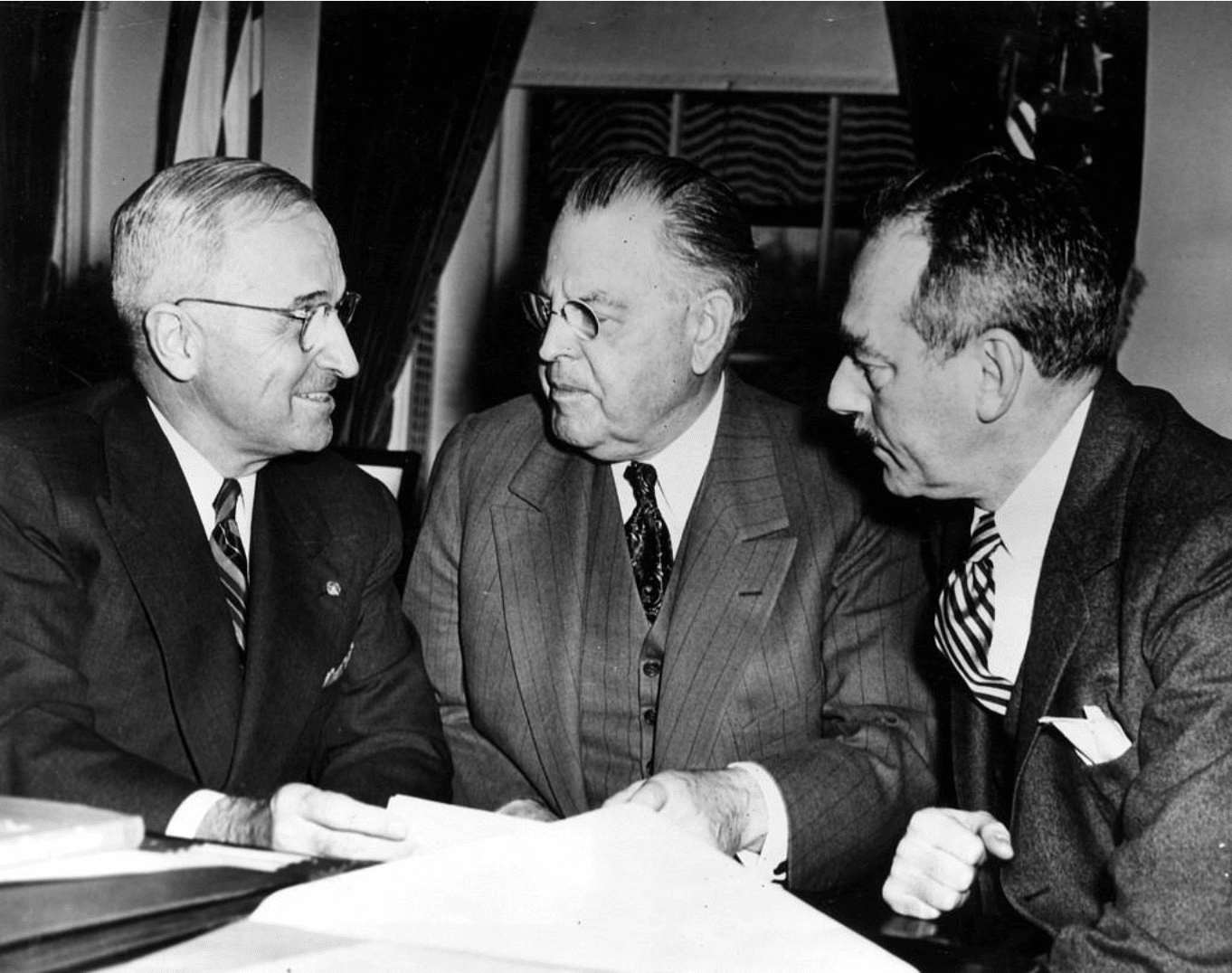

By June 1950, Acheson was still grappling with the question of Taiwan’s future. At a meeting held at the Willard Hotel in Washington DC, he and several senior officials discussed various scenarios for the island, including the possibility of replacing Chiang. The meeting reflected the depth of American frustration with Chiang’s leadership and the desire to stabilize Taiwan as a potential bulwark against communism.

However, events overtook these deliberations. News arrived during the meeting that war had broken out on the Korean Peninsula. Fearing domestic backlash, the “loss of Korea” coming right on the heels of the communist victory in China, the Truman administration chose to embrace containment of communism across Asia, thereby abruptly ending discussions of removing Chiang. The United States quickly committed to defending Taiwan under Chiang’s leadership, sending the Seventh Fleet to the Taiwan Strait and making him an indispensable, if reluctant, partner in its Cold War strategy.

Acheson’s fleeting considerations to replace Chiang Kai-shek offer a revealing glimpse into the fluidity of American foreign policy during the early Cold War. While they ultimately came to nothing, these plans highlight the Truman administration’s uncertainty about Taiwan’s future and its broader struggle to adapt to the rapid shifts of the postwar world.

In retrospect, Acheson’s skepticism about Chiang was well-founded. Taiwan under Chiang was anything but pleasant, his immediate authoritarian rule featuring mass political repression, years of economic instability, and violence against its native population. Yet in Acheson’s view the outbreak of the Korean War foreclosed alternative approaches, tying U.S. policy to the KMT for decades to come.

The debate over Chiang Kai-shek’s leadership in 1949-1950 remains an important, if underexplored, episode in the history of American foreign policy in the post-war years. It underscores the contingency of U.S. Cold War strategy and the extent to which reaction to global events and domestic political considerations, rather than deliberate forethought, shaped policy decisions. Acheson’s brief consideration of replacing Chiang ultimately gave way to the exigencies of containment, but it serves as a reminder of the alternative paths not taken in this pivotal moment in history.

It needn’t, in other words, have been the way it was and has been.

As economist Murray Rothbard noted at the time, this policy of defending Taiwan was always based on fallacious reasoning, parroted to this day by the current crop of hawks:

“A peaceful Pacific moat is needed for our defense. In order to protect this moat, we must secure friendly countries or bases all around it. To protect Japan and the Philippines, we must defend Formosa [Taiwan]. To protect Formosa we must defend the Pescadores. To protect the Pescadores we must defend Quemoy, an island three miles off the Chinese mainland. To protect Quemoy we must equip Chiang’s troops for an invasion of the mainland. Where does this process end? Logically, never.”

And that is precisely the point.