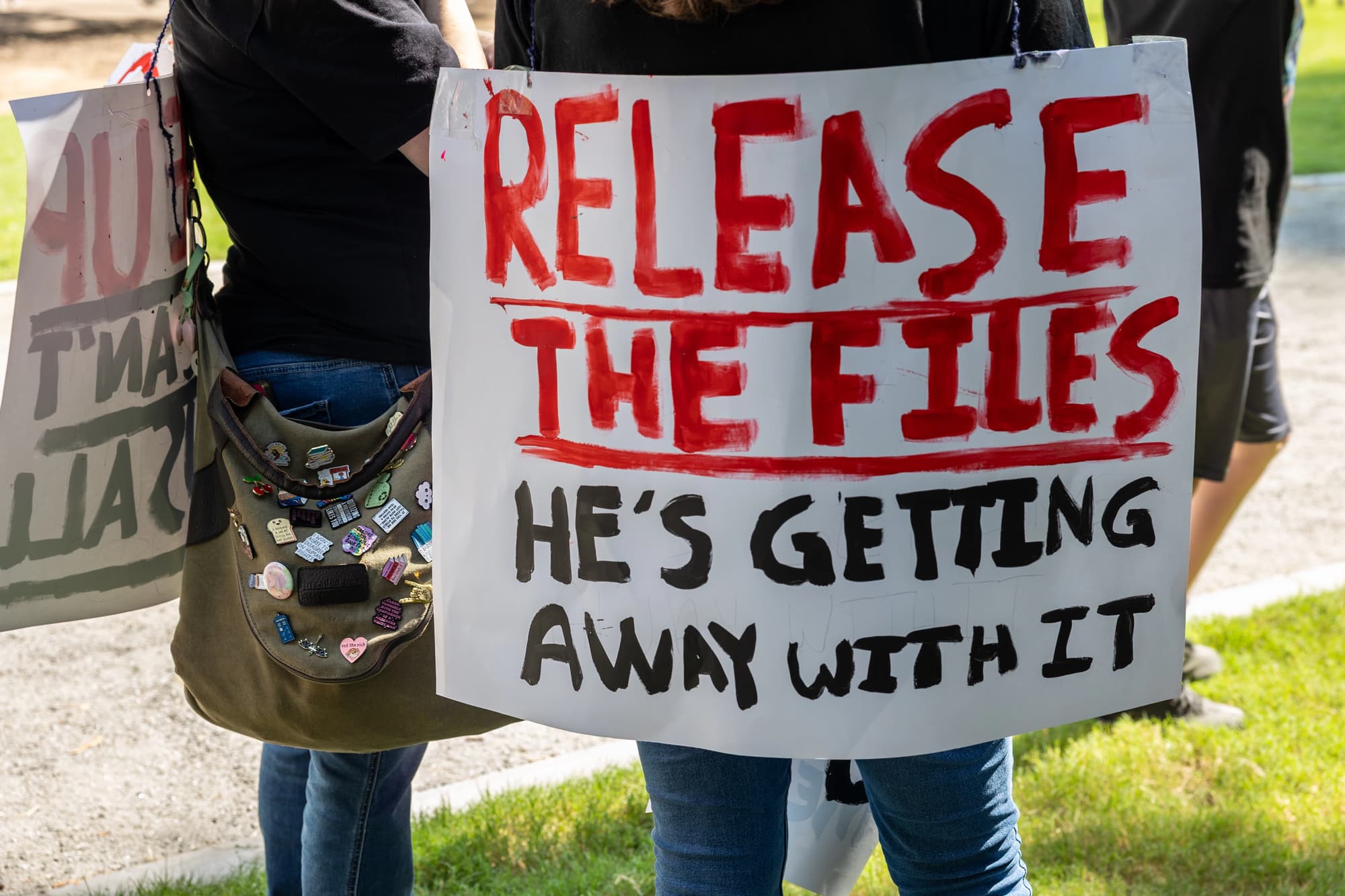

Public discussion of the Epstein files has largely centered on individual misconduct and reputational fallout. That emphasis risks overlooking the more consequential question raised by the Justice Department’s response to the disclosure mandate. The episode is less instructive as a scandal than as an example of how executive institutions behave when transparency carries political cost. What is at stake is not the identity of those named in the records, but how legal obligations are treated once compliance becomes inconvenient.

Congress attempted to limit executive discretion through the Epstein Files Transparency Act. It was signed into law on November 19, 2025. The statute required the release of all unclassified Justice Department records related to Jeffrey Epstein within thirty days. It was unusually explicit, narrowing permissible redactions and barring withholding for reputational or political reasons. By design, the law sought to reduce delay by removing ambiguity rather than relying on voluntary cooperation.

That effort fell short. The Department of Justice missed the statutory deadline, released only a portion of the required records, and applied extensive redactions without a detailed public explanation at the time. Subsequent reporting indicated that several documents initially posted were later removed from the department’s website, according to Al Jazeera. The department also indicated that additional materials would be released at a later date, effectively extending a deadline Congress had already set.

What matters here is less what the records suggest about particular individuals than what the episode reveals about enforcement. When a statute imposes a clear obligation but noncompliance carries no immediate consequence, the obligation weakens in practice. Compliance becomes conditional. This dynamic is familiar in other areas of executive authority, but the clarity of the statute makes it harder to dismiss as routine bureaucratic delay.

Public attention has largely focused on elite reputations. Yet credibility in American political life has rarely depended on moral standing alone. It has been sustained by institutional insulation, legal privileges, procedural barriers, and discretionary enforcement that limit exposure to consequence. The Epstein disclosures unsettle that arrangement not by exposing hypocrisy, but by making those protective mechanisms more visible.

Elite moral standing has never rested on transparency by itself. It has relied on narrative management and on institutional buffers that absorb political risk. When those buffers hold, reputational damage remains contained. When they weaken, confidence erodes. The present controversy reflects that erosion. It is not evidence of a sudden ethical collapse, but of declining faith in the mechanisms that once kept misconduct marginal and manageable.

The Justice Department’s response illustrates how impunity operates as a structural feature rather than an exception. Congress retains theoretical enforcement tools, including criminal contempt referrals, civil litigation, and inherent contempt. In practice, most of these mechanisms depend on the executive branch itself. Criminal contempt referrals are handled by the Justice Department. Civil suits move slowly and frequently defer to claims of privilege. Inherent contempt, while constitutionally available, has not been used to detain a federal official in nearly a century.

This structure produces predictable incentives. Executive agencies know that delay or partial compliance is unlikely to trigger meaningful penalties. Negotiated disclosure becomes a rational response. In this sense, the Epstein disclosures echo other episodes where official misconduct became public, but meaningful consequences failed to follow.

What distinguishes this episode is not the nature of the misconduct, but the lack of interpretive flexibility in the statute itself. The Epstein Files law explicitly required disclosure of internal Justice Department communications and barred withholding to protect reputations. When common-law privileges are invoked to narrow a statute designed to override them, institutional self-protection takes precedence over legislative command.

Transparency alone does not resolve this imbalance. In some cases, it reinforces it. Partial disclosure and heavy redaction can create the appearance of compliance while leaving the underlying distribution of power intact. Over time, this pattern conditions both officials and the public to treat disclosure as an endpoint rather than as a step toward accountability.

The broader implication is not that elites are uniquely immoral. It is that the structure of the modern administrative state rewards insulation. Concentrated authority combined with weak enforcement produces consistent outcomes regardless of who occupies office. The same design that shields political allies today can just as easily shield their successors tomorrow. From a libertarian perspective, the problem is unchecked discretion, not partisan advantage.

Viewed this way, the Epstein files function as a case study in governance rather than scandal. They show how laws intended to constrain executive behavior falter when enforcement depends on the goodwill of the institutions being constrained. They also help explain why elite credibility erodes when transparency is separated from consequence. Trust does not fail because uncomfortable facts emerge. It fails when legal mandates can be ignored without cost.

If Congress does not enforce its own statutes, future transparency laws will operate largely as symbolic gestures. Executive agencies will continue to weigh compliance against political exposure, and elite credibility will persist so long as institutional protections remain intact. This is less a moral failure than a structural one. Until enforcement mechanisms operate independently of executive discretion, impunity will remain a feature of the system rather than a deviation from it.