Since Libertarian Institute Director Scott Horton published Provoked: How Washington Started The New Cold War With Russia And The Catastrophe In Ukraine in November, there has been a renewed intellectual struggle between antiwar Americans and the War Party.

Horton has been making the rounds on both independent and power faction media to tell the American people the truth about Washington DC’s duplicity in Ukraine. For his troubles, he has been repetitiously slandered and libeled by War Party apparatchiks. The British historian Niall Ferguson, for one high profile example, accused Horton of “recycling Kremlin propaganda.”

Meanwhile, in addition to the eminent personages already featured on its backend, last week a former CIA officer and best-selling thriller novelist endorsed Provoked as well.

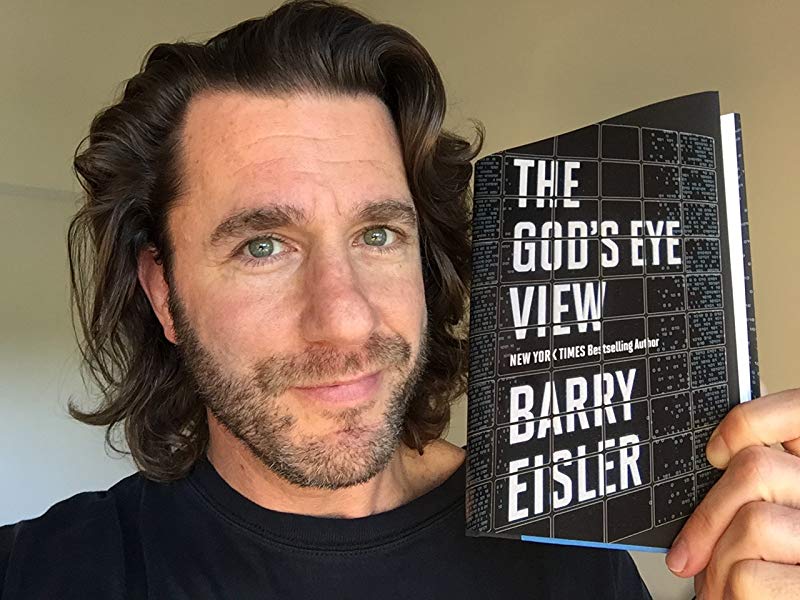

Barry Eisler, who “spent three years in a covert position with the CIA’s Directorate of Operations” and now writes fictional works of spooks, special forces, and assassins, wrote a powerful and compelling review of Provoked:

“…it’s dispiriting that this book even needed to be written, the reality is that propaganda is a powerful force and requires a powerful corrective.”

Eisler is a fascinating figure to juxtapose with Ferguson. While Ferguson uses “non-fiction” to peddle imperialist lies, Eilser uses fiction to tell the truth about human nature and the institutions of proactive aggression that we build. Eisler told this writer that his current work in progress is “the most Horton-adjacent” thriller he’s ever written, but that his 2016 novel The God’s Eye View is the published work closest to Horton’s oeuvre.

Inspired by Edward Snowden’s NSA revelations, The God’s Eye View is reminiscent of Stephen King’s 1980 novel Firestarter. Eisler’s villain, NSA Director General Theodore “the Director” Anders, is as cold and terrifying as King’s Captain James “Cap” Hollister, director of the Department of Scientific Intelligence (aka The Shop). Its primary assassin, Manus, is a wounded killer channeling the same archetype as King’s Rainbird. And the protagonist, Evelyn Gallagher, struggles with the same moral qualms as King’s Andy when it comes to serving the malevolent agenda of the state.

Unlike Stephen King, however, Eisler is the kind of guy who knows what a tactical reload is. His novel is filled with John Wick-levels of action but also sublime meditations on tradecraft. And it’s got some deep philosophical underpinnings.

The novel continually circles the theme of corporate agency, so much so that one wonders if Eisler studied under American philosopher Kendy Hess. The National Security Agency is expertly evoked as one mind with many bodies; a super organism comprised of its employees. General Anders is obsessed with maintaining the health of that body, of guarding it from “contagion.”

There is an examination of the tensions between kinship and caste and the competing loyalties of biological family, shared humanity, the command chains of the national security apparatus, and the imagined community of the nation. There are guns, knives, fist fights, explosions, and badass one-liners. Eisler is so adept at filling his violent world with all the accoutrements of bourgeois reality you can almost taste the specialty coffee.

The intellectual scope of the novel is revealed immediately. The German philosopher Martin Heiddeger apocryphally once spent an entire semester focusing on the opening line in Plato’s The Republic, and we could do the same with Eisler’s opening line:

“General Theodore Anders was dreaming of marlin fishing when the secure phone rang on the bed stand next to him.”

The word “general” is so fascinating. It has the market meaning of broad and inclusive goods but also the meaning of highest rank in the U.S. Army. The position isn’t broad, but its authority and responsibilities are. The National Security Agency is always run by a general and that person has a privileged place within the body of the corporate agent. Sitting at “headquarters,” they approximate a deeper symbolic mastery of the agent’s Rational Point of View (RPV). Anders has a big picture view of what’s going on and why, whereas an employee like Manus simply submits to the RPV by following orders and doing his job.

Theodore Anders. Theodore carries the meaning of “gift from God” and Anders can mean “manly” and “warrior.” General Anders is a hero of Desert Storm who aspires to godlike power. And let’s not overlook the link between “Anders” and “Anderson,” Neo’s slave name in The Matrix. What is the state if not the steward of the consensual hallucination that is the matrix?

Was dreaming. Anders is within his unconscious. The NSA is the nation’s unconscious. It is the nation’s muse. Not in the sense of a young woman who inspires Leonardo DiCaprio’s next performance, but a goddess of memory, of “total recall.”

Fishing invokes Jesus Christ as the fisher of souls and marlin fishing draws a line to Ernest Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea, and from there to Herman Melville’s Moby Dick.

The secure phone that wakes Anders up symbolizes the dawning of consciousness.

It’s a lot of symbolism, allusion, and meaning to fit into one sentence and Eisler does it masterfully. The content and themes that he explores are also central to Horton’s Provoked, so it is not surprising that Eisler enjoyed it.

In real life, we have people obsessed with the state’s claims to divinity and unbounded power who are daily risking the existence of humanity with their hubris, their mendacity, and their mediocrity. And we have intellectuals like Ferguson who enlist themselves as apologists for such monstrosity.

Fortunately we have men like Horton and Eisler. One writes history. One writes fiction. Both write thrillers and both tell us the truth.