The Treasury Department released new budget deficit numbers this week, and with two months still to go in the fiscal year, 2019’s budget deficit is the highest its been since the US was still being flooded with fiscal stimulus dollars back in 2012.

As of July 2019, the year-to-date budget deficit was 866 billion dollars. The last time it was this high was the 2012 fiscal year when the deficit reached nearly 1.1 trillion dollars.

At the height of the recession-stimulus-panic, the deficit had reached 1.4 trillion in 2009. (The 2019 deficit is year-to-date):

What is especially notable about the current deficit is that it has occurred during a time of economic expansion, when, presumably, deficits should be much smaller.

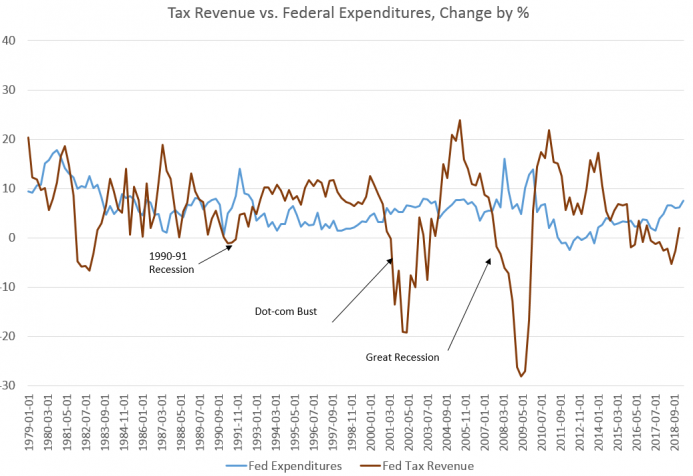

For example, after the 1990-91 recession, deficits generally got smaller, until growing again in the wake of the Dot-com bust. Deficits then shrank during the short expansion from 2002 to 2007. During the first part of the post Great Recession expansion, deficits shrank again. But since late 2015, deficits have only gotten larger, and are quickly heading toward some of the largest non-recession deficits we’ve ever seen.

The situation is a result of both growing federal spending and falling tax revenues. As of the second quarter of 2019, year-over-year growth was nearly at a nine-year high. Federal spending rose 7.5 percent, year over year, during the second quarter of this year. The last time growth rose as much was during the first quarter of 2010 when spending increased 13.8 percent, year over year.

Meanwhile, federal revenue growth has fallen, with only one quarter out of the last eight showing year-over-year growth.

Historically, a widening gap between tax revenue and government spending tends to indicate a recession or a period immediately following a recession. We saw this pattern during the 1990-91 recession, the Dot-com recession, and the Great Recession.

The Trump administration has attempted to brag that it has increased revenues through tax hikes (i.e., tariff increases), and as Bloomberg reports, “tariffs imposed by the Trump administration helped almost double customs duties to $57 billion in the period.”

But tariff hikes also cut intro entrepreneurial activity and overall production, reducing earnings and hobbling economic growth. Not surprisingly, tax revenues have not kept up.

Of course, if tax revenues actually limited government spending, there wouldn’t be much to complain about. Lower revenues really would mean fewer resources flowing into government coffers — and that can be a good thing.

[RELATED: “Deficits Do Matter: Debt Payments Will Consume Trillions of Dollars in Coming Years” by Ryan McMaken]

But, in a world where government borrowing allows spending to balloon even in times of falling revenue, we’re setting the stage for future problems. The more the total national debt rises, the more debt service will become a serious issue if interest rates increase even moderately. Given the prospects for higher interest rates in the future, the Congressional Budget Office estimates interest payments on the debt will increase substantially in the future:

It is troubling that after a decade of an economic expansion, the US government is still spending money as it does during and immediately following a recession. Thus, if deficits are this large right now when times are good, how big will they become when the US enters recession territory? Back in 2009, the recession and its aftermath (i.e., massive amoounts of stimulus) drove deficits beyond the trillion dollar mark four years in a row. With 2019’s deficit total now pushing toward 900 billion, we should perhaps expect deficits to top two trillion when the next recession hits. And probably for several years.

The piper will then need to be paid when interest rates increase and substantial cuts must be made to social security, medicare, and to military budgets in order to service the debt and avoid default.

This reckoning can be put off, however, so long as the dollar remains the world’s reserve currency, and the central bank can continue to monetize the debt. As long as the dollar reigns supreme, the central bank can keep this up without causing high levels of price inflation. But when the day comes that the dollar can no longer count on being stockpiled worldwide, things will look very different.

The central bank won’t be able to simply buy up debt at will anymore, interest rates will rise, and Congress will have to make choices about how many government amenities will be cut in order to pay the interest bill. Americans who live off federal programs will feel the pinch. State governments will have to scale back as federal grants dry up. The US will have to scale back its overstretched foreign policy. Not all of this is a problem, of course. But lower-income households and the elderly will suffer the most. Everything may seem fine now, but by running headlong into massive deficits even during a boom, the feds are setting up the economy for failure in the future.

But that’s in the future, and few lawmakers in Washington are worried about much of anything beyond the next election cycle.