One of the most unexamined—and almost unmentioned—economic realities of post-gold standard America is the change in America’s economic growth rate since the gold window closed in 1971.

Does inflation change the rate of economic growth? The Federal Reserve Bank claims on its website that “inflation that is too low can weaken the economy.”

Therefore, the Federal Reserve Bank claims it wants permanent inflation as policy: “The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) judges that inflation of 2 percent over the longer run, as measured by the annual change in the price index for personal consumption expenditures, is most consistent with the Federal Reserve’s mandate for maximum employment and price stability.”

While it is an economic fact that prices tend to fall during a recession or depression in the short term, is there any real-world empirical evidence to back up the Fed’s claim that moderate inflation over the long run helps economic growth?

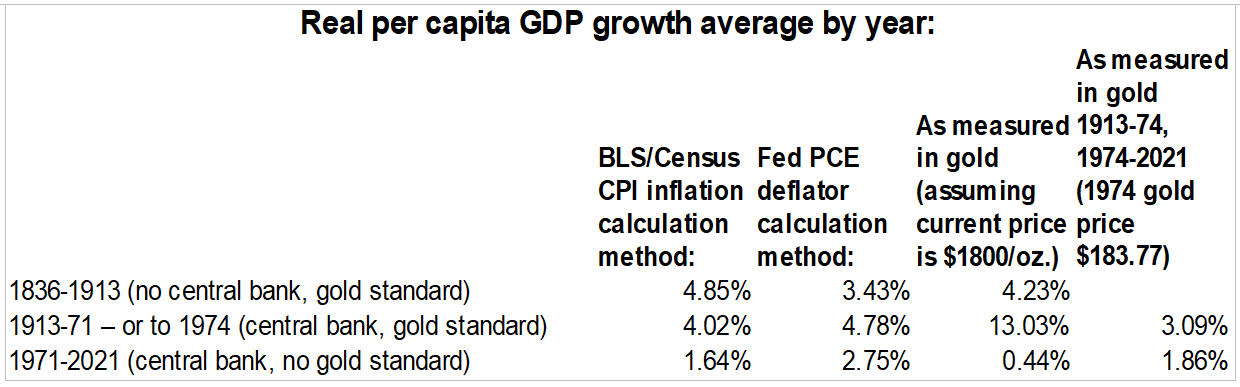

Using data from the Federal Reserve Bank and the U.S. Census Bureau, it’s possible to calculate an average economic growth rate during the three most recent economic periods of American history, two of which had low or negative price inflation levels:

- 1836-1913: The free banking era that began with the close of the Second Bank of the United States in 1836 and ended with the founding of the Federal Reserve Bank had slight negative price inflation.

- 1913-1971: The first Federal Reserve Bank era with a gold standard, which had slight, long-term price inflation of less than two percent annually.

- 1971-present: The second Federal Reserve Bank period without a gold standard since 1971 initially had price inflation higher than the Federal Reserve’s target levels, though since the late 1980s it has kept very close to the Fed’s present target.

I took these three periods and used the Census Bureau’s annual raw GDP numbers since 1836 as well as the bureau’s U.S. population numbers by year, and then calculated a raw GDP number per capita. Finally, I calculated the annual rate of increase (or decrease) in GDP to get a real rate of increase, and then added in turn each of three variables which account for price inflation: PCE deflator, the Consumer Price Index, and the price of gold.

The data shows that the rate of increase in wealth produced by each American has roughly been cut in half since the gold window closed and the United States gradually weaned itself off the gold standard in 1971-74.

The above table shows that by any of the three methods of inflation accounting the rate of economic growth has diminished since the dawn of the age of inflation. Under the three, the Fed’s preferred method—the PCE deflator—makes the current post-gold standard era look best. But even this method shows that growth has been cut by nearly half from the previous era.

Measuring economic growth by the price of gold using the 1971 break from the gold standard makes the first Federal Reserve Bank era look like unprecedented growth (13% annually), and all but disappears the current era growth (less than 0.5% annually). This is primarily because the price of gold in 1971 remained artificially suppressed to $35/ounce even as the currency and other prices had already been inflated. If the break point is extended to 1974—when gold first floated freely—instead of 1971, the numbers are more reflective of the other inflation metrics.

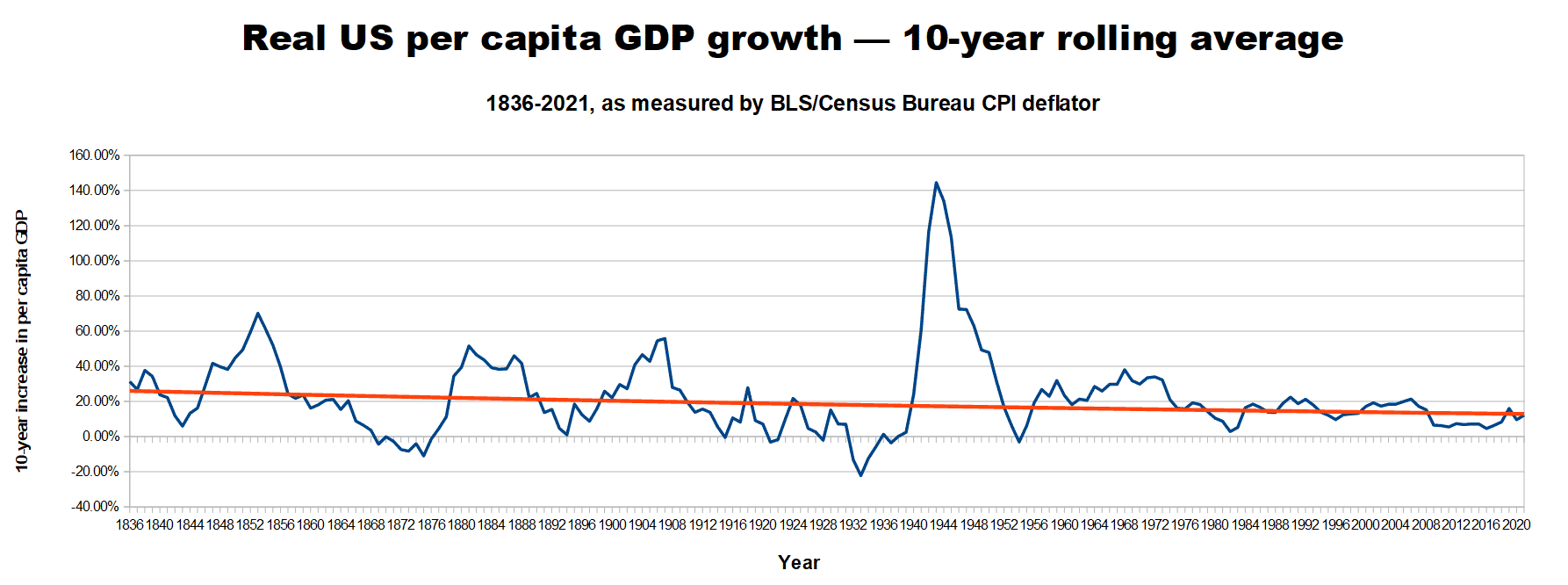

The annual rate of increase in real per capita GDP has particularly fallen in the past two decades, a time when the Fed was closest to its stated inflation target, as revealed in the chart below.

While this data doesn’t prove that long-term inflation decreases economic growth, it does show that the Federal Reserve Bank’s assertion that “inflation that is too low can weaken the economy” is without any empirical foundation. It does, however, tend to discredit the Keynesian dogma that inflation encourages consumption, which leads to economic growth and full employment. Instead—even though there are clearly a great many other variables in historic U.S. economic growth, such as the devastating Civil War—the data tends to back up the intuition that inflation discourages savings, and that economies with high savings rates tend to have faster economic growth.

The age of inflation, which the United States formally entered in 1971, has not only ushered in a period of lower overall economic growth, but also a time when income disparity has increased dramatically, leaving all the economic gains to the wealthier classes of people.