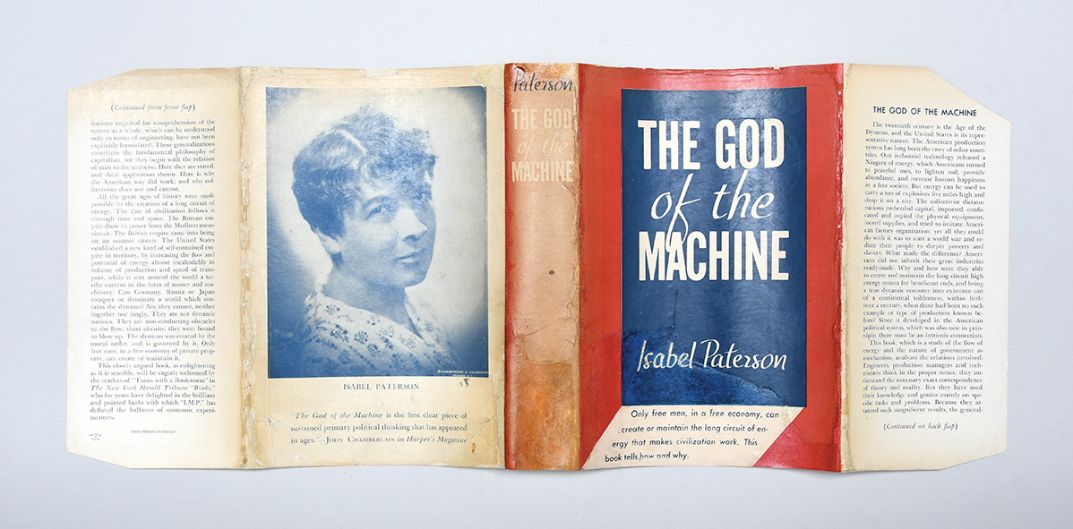

January 22 is a convenient reminder that modern American libertarianism did not begin only in seminar rooms, courtrooms, or party platforms. It also began on the book page, where a few writers treated state worship as an intellectual mistake rather than a civic duty. In 1943, three books appeared that, as one later institutional summary puts it, “changed American politics forever.” Those books were Isabel Paterson’s The God of the Machine, Rose Wilder Lane’s The Discovery of Freedom, and Ayn Rand’s The Fountainhead. Together, they supplied a moral and analytic vocabulary that later organizers and scholars would treat as a seed crystal for modern American libertarianism.

Paterson is sometimes filed away as an influence on Rand and Lane, as if she were merely a rung on someone else’s ladder. That is a category error. Her writing stands on its own: incisive, impatient with can’t, and suspicious of any program that requires other people to be “improved” at gunpoint.

The plain biographical facts already hint at why she distrusted authority. Isabel Mary Bowler was born on Manitoulin Island in Ontario on January 22, 1886, married Kenneth Birrell Paterson in 1910, and separated from him in 1918. She built her career in journalism, moved to New York, joined the New York Herald-Tribune in 1922, began her long-running column “Turns With a Bookworm” in 1924, and wrote both fiction and political analysis. After her dismissal from the paper in 1949, she continued writing, refused Social Security benefits, and died in 1961. The archival inventory preserves the working writer’s paper trail: drafts, contracts, legal documents, and extensive files of her columns and reviews.

A more textured picture comes from the sort of details that rarely fit into polished origin stories: poverty, irregular schooling, and work that had to pay. Paterson grew up in a family that repeatedly moved in search of stability, had minimal formal education, and read voraciously. After leaving home she worked in Calgary, married unhappily, and began her journalistic career at the Spokane Inland Herald before moving to New York and becoming a U.S. citizen in 1928. Her career then took off when she began “Turns With a Bookworm,” a platform that carried her “biting wit and hard-hitting prose” to a vast readership and made prominent authors “sometimes” fear her verdicts.

Paterson’s own fiction shows that temperament before it hardened into political theory. In The Magpie’s Nest, a character rejects the most respectable kind of dependence with a single dry line: “Not that. Expensive, but I like to own myself.” Earlier in the same novel, Paterson skewers the town’s self-important “Round Up Club” by describing the members as “fat and tubby gentlemen” who would have been miserable “on the hurricane deck of a bronco.” Even when she is writing about social pretension rather than policy, her targets are recognizable: status treated as virtue, privilege treated as merit, and arrogance disguised as “leadership.”

Paterson wrote novels, but her public leverage came from criticism: the steady, public habit of judging books and ideas. That work demanded two skills political thinkers often lack in combination: she had to be fair enough to be trusted, and sharp enough to be read. Stephen Cox, writing about her career and style, stresses her distinctiveness—“Nobody ever mistook a page of Paterson for a page of anybody else”—and he captures her snap-and-cut manner with examples like her definition of psychology as “a science which tells you what psychologists are like.” That is not just a joke; it is a method. She used humor the way a surgeon uses a scalpel: to remove the dead tissue of fashionable language and expose what was underneath.

A later scholarly edition underscores how much of her work lived outside book covers. Culture and Liberty: Writings of Isabel Paterson (edited by Cox) gathers essays, reviews, and letters that were out of print or never published, and it highlights the combination most readers first encountered: radical individualism delivered with provocatively readable prose. Paterson’s reputation for wit is not a decorative biographical detail; it is part of her intellectual effect. She made it easier for readers to doubt the state’s self-flattery because she made that flattery look ridiculous.

Paterson’s sharpness had an unusually clear target: the sanctimony that surrounds state action. She did not treat government as a neutral tool that becomes good or bad depending on who holds it. She treated it as a structure that rewards coercion and moralizes its own expansion. Jennifer Burns, in her scholarly study of Paterson, Lane, and Rand, summarizes Paterson’s conclusion with a sentence that has the shape of a law: “[T]he well being of the citizen exists in direct inverse ratio to the power of the state.” That line is not a mood. It is a diagnosis, and it helps explain why she could be both funny and unyielding when others were becoming reverent about “solutions.”

What made her attacks bite was that she aimed at “sacred cows” rather than obvious villains. The danger, in her telling, was not only the corrupt politician. It was the sincere reformer who assumes that good intentions turn coercion into righteousness. Once government is described as a dispenser of “benefits,” it becomes morally unsearchable, and that is exactly when it is most likely to be used as a weapon.

In The God of the Machine, Paterson tried to explain why free societies produce wealth, invention, and cultural complexity, while planned societies so often produce shortages, stagnation, and fear. She did it by building an extended metaphor of an “energy circuit.” The productive individual is the generator. “In the social organization,” she writes, “man is the dynamo, in his productive capacity.” Government, by contrast, is “an end-appliance,” and “a dead end” with respect to the energy it consumes. The point is not that society runs on selfishness, but that it runs on initiative—and initiative cannot be conscripted into existence. Paterson sharpened the argument against economic determinism with a question that sounds almost impatient. “Where do you get your economics to interpret,” when the so-called “economic conditions” “don’t just happen, like the weather.” Production depends on ideas; political authority can seize the product, but it cannot originate it. That is the point, and it is why political “planning” keeps raiding the productive economy without understanding the source of the inputs. In her terms, the only defensible state is one that guards the long circuit without pretending to be its generator.

The book’s sting is not separable from that metaphor. Even the chapter titles are arguments, not decorations: “The Fiction of Public Ownership,” “Our Japanized Educational System,” and, most memorably, “The Humanitarian with the Guillotine.” Paterson’s barb works because it names a structural truth: coercion does not stop being coercion because it is performed in the name of mercy. A government that can “do good” can also compel compliance, and the same power supplies both functions.

Readers in 1943 understood that Paterson was offering more than a clever phrase. A reviewer in Harper’s Magazine proposed pairing her book against Harold Laski’s collectivism for a “seminar on the individual versus the mass,” and then summarized the contrast with brutal simplicity: “Laski believes the individual must serve society; Mrs. Paterson believes the individual can best serve society by helping himself.” Paterson’s position is not a denial of social obligation; it is an insistence that obligation cannot be reduced to obedience, and that service coerced by the state is not service but submission.

Paterson’s influence is easiest to see in the people who took her seriously when it was unfashionable to do so. She shaped conversations inside the mid-century anti-New Deal milieu, and she directly affected writers who later reached far larger audiences. Her ideas could be hostile to intellectual laziness, but they were also hospitable to anyone willing to follow an argument to its endpoint.

Ayn Rand put Paterson’s impact into an unguarded form in a 1943 letter to publisher Earle H. Balch, calling The God of the Machine “a document that could literally save the world,” and insisting that it did “for capitalism what the Bible did for Christianity.” The comparison is extravagant, but the underlying point is sober. In politics, feelings do not substitute for arguments, and Paterson supplied arguments sturdy enough to become a worldview.

Later libertarian leaders have been less lyrical, but not less emphatic about her place in the lineage. In one of his final public reflections, David Boaz urged that we remember “three founding mothers of the modern libertarian movement,” and then added, with the kind of punch Paterson herself would have enjoyed, “We should have their pictures on everything.” It is a joke with an edge: movements tend to canonize institutions, and forget the writers who supplied the intellectual ammunition before there were institutions to join.

That is why Paterson is worth reading not just on January 22. She attacked the sacred cows of the state because she refused to treat power as sacred. She also refused to treat the individual as a ward of “society,” fit only to be managed. In an age drowning in official benevolence, her most enduring contribution may be her most bracing reminder: liberty is not granted by the state, and it is not maintained by good intentions. It is maintained by people who insist on limits, and who keep insisting when the moralizers call them selfish for doing so.