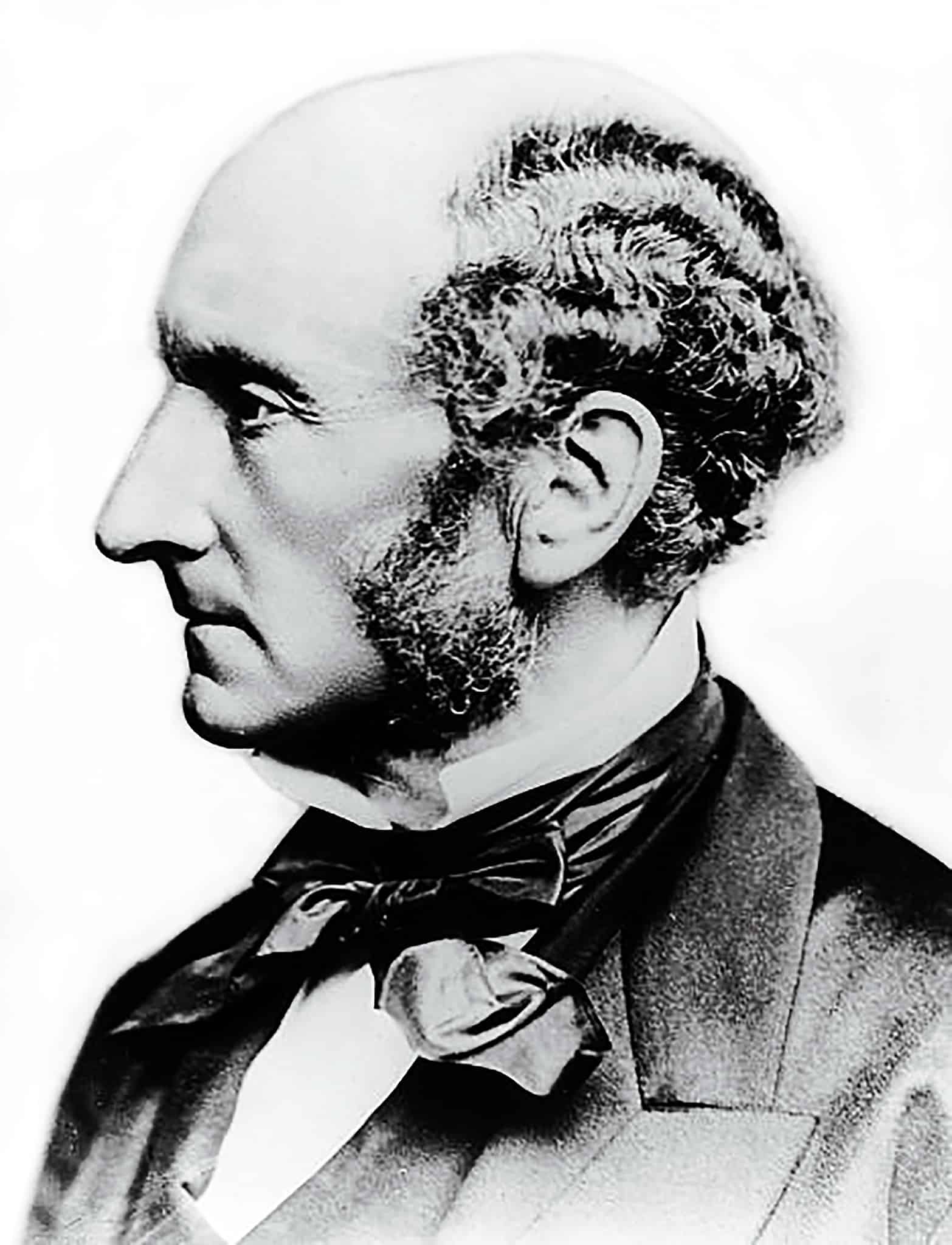

In The Struggle for Liberty, Ralph Raico—one of the twentieth century’s foremost libertarian historians—offers a sweeping and penetrating critique of John Stuart Mill. With clarity, historical depth, and a touch of well-placed fire, Raico demolishes the myth that Mill belongs in the pantheon of classical liberalism. Instead, Raico exposes Mill as a forerunner of the modern progressive state: one who stripped liberalism of its essential emphasis on economic freedom and opened the door to a new, coercive moralism enforced by government.

This critique is more than academic—it goes to the heart of how the liberal tradition is understood and misrepresented, even by those typically reliable in defense of liberty. As Raico argues, Mill’s legacy is deeply misunderstood. His influence marked a decisive shift from the laissez-faire liberalism of figures like Frederic Bastiat, Herbert Spencer, and Wilhelm von Humboldt to a form of moralized statism cloaked in the language of freedom. And tragically, that misunderstanding persists, with thinkers as influential as Friedrich Hayek miscasting Mill as a genuine heir of the classical liberal tradition.

Raico begins his critique by grounding liberalism in its classical roots: a commitment to individual liberty, private property, free exchange, and radical limits on the state. This liberalism—emerging in the context of Europe’s decentralized medieval institutions and reaching its high point in the nineteenth century—viewed the state primarily as a threat to liberty. True liberals sought to constrain it, not empower it. Yet, John Stuart Mill, in On Liberty and elsewhere, reimagined liberalism as an idealist project of moral and social uplift, one that increasingly called upon state power not merely to protect rights, but to cultivate the “higher” faculties of the individual and to shape society according to utilitarian visions of the good.

Mill’s conception of liberty, Raico points out, is far removed from the “freedom from” of traditional liberalism (freedom from coercion, taxation, or regulation). Instead, Mill introduces the idea of “freedom to”—freedom to self-actualize, to improve, to transcend convention. At first blush, this sounds noble. But for Raico, the problem lies in the shift of authority: who gets to decide what counts as improvement? For Mill, the answer is disturbingly clear—if social customs or traditional morality prevent an individual from reaching what he considers a higher level of being, the state may justifiably intervene. As Raico puts it, Mill “opened the door to hedonistic relativism backed by state coercion.”

This is not the vision of liberty held by earlier liberals like von Humboldt—whom Mill praises, but does not follow. Where Humboldt stressed the autonomy of the individual and the strict delimitation of state action, Mill shifted focus toward state-managed progress. In doing so, he inadvertently set the stage for the very forms of moral paternalism that classical liberals had opposed for centuries. Under Mill’s influence, the state became not just a protector of freedom but a promoter of “higher” values, capable of molding individuals into what elite reformers think they ought to be.

For Raico, this is not merely a theoretical misstep—it has real-world consequences. Mill’s ideas helped lay the intellectual groundwork for the modern welfare-warfare state. Where the older liberals feared empire, bureaucracy, and centralized control, Mill admired the British empire and supported foreign interventions to “civilize” lesser peoples. At home, his flexible utilitarianism made room for growing state intrusions in the name of moral or social improvement.

Raico’s analysis is deeply revisionist, and that is its strength. He challenges the standard canon of liberalism not by discarding its insights but by clarifying its boundaries. Mill, Raico insists, belongs not to the lineage of radical classical liberals like Richard Cobden, Gustave de Molinari, or William Leggett, but rather to the ideological ancestors of modern progressive liberalism. Mill’s shift from rights to outcomes, from liberty as self-ownership to liberty as self-realization, distorts the classical liberal project and turns it into something far more dangerous: a technocratic managerialism that justifies using state power to enforce a particular vision of human flourishing—whether citizens want it or not.

This critique gains even more weight thanks to the editorial work of Ryan McMaken, whose painstaking transcription and annotation of Raico’s 2004 lectures at the Ludwig von Mises Institute bring this powerful analysis to a new generation of readers. McMaken has helped ensure that Raico’s warnings about Mill—and about the betrayal of classical liberalism by modern liberal intellectuals—won’t be forgotten. As McMaken notes in the introduction, The Struggle for Liberty represents Raico’s most cohesive historical narrative, weaving together deep learning, sharp analysis, and the passion of a man determined to defend the cause of liberty.

Raico’s project is both corrective and constructive. By denouncing Mill’s mischaracterization as a classical liberal, he aims to recover the true lineage of liberalism—one rooted in property, voluntary exchange, moral responsibility, and the dignity of restraint. He invites us to reread the liberal tradition not as a march toward modern progressive values, but as a struggle to protect society from precisely that kind of moral crusading via government.

In the end, Raico’s judgment is clear: Mill does not belong in the liberal pantheon as a hero, but rather as a cautionary tale. His legacy is one of well-intentioned betrayal—a transformation of liberalism into an ideology that forgets its original mission and becomes an enabler of state coercion in service of elite-approved virtue. Against this backdrop, Raico’s work is a rallying cry for all who value freedom not as the fulfillment of some idealized personality, but as the space within which individuals pursue their own ends—free from the tutelage of the state.

For those who cherish the real liberal tradition, The Struggle for Liberty is essential reading. Thanks to the dedicated work of Ryan McMaken and the Mises Institute, Ralph Raico’s fierce and brilliant voice continues to remind us what liberty truly means—and why it must be defended not only from its enemies, but also from its false friends.