“What is a journalist?” is a contemporary equivalent of the ancient question, “What is truth?” The U.S. government’s prosecution of Julian Assange hinges on the assertion that he is not a journalist and should be punished like a spy for a hostile country. The controversy over Assange is part of broader clashes over the meaning of journalism and freedom of the press across the United States.

I recently wrangled on this topic with former top-ranked New York City radio host Brian Wilson, with whom I do a weekly podcast. In one of his Substack essays on the topic, Brian stated that “anyone claiming the title ‘Journalist’ must come with the degreed qualifications”—possessing a journalism degree. He added, “I take principled offense at those who appropriate a title they never earned” by not possessing a journalism degree. Commenting on a recent dispute over the firing of former Republican National Committee Chairwoman Ronna McDaniel, Brian mentioned that some of the individuals that NBC identified as “journalists” had not graduated from college. Brian declared, “Wouldn’t you expect a professional ‘journalist’ to have bona fide credentials on a par with other professions”—such as doctors and lawyers —”to qualify for their titles”?

Brian stated that a journalism degree “should be obviously important to anyone looking for Integrity and Accuracy in the news.” But ethics is a shaky defense for “degreed Journalists.” In the past thirty years, the percentage of people working for print and broadcast media outlets who have journalism degrees has skyrocketed. At the same time, public trust in the media collapsed.

Brian stated that in all the years that he knew me and followed my work, he had never heard of anyone refer to me as a “journalist.” Actually, that is probably the most common non-profane term folks use to describe me.

But I am a mere Hokie dropout, since I didn’t finish a four-year sojourn at Virginia Tech. I never took any journalism classes. On the other hand, I zealously pursued classes and independent studies with professors to become a better writer. Once I took all those classes, I dropped out because having a degree from Va. Tech wouldn’t open the type of markets I planned to target. Early on, I found some editors that judged me by the words I submitted, not by any academic pedigree.

Maybe my career illustrates the shifting definitions and standards for journalism. After I moved to Washington in mid-1980, I applied to be a writer or researcher at the Heritage Foundation. At that point, Heritage did not have a grandiose law firm-style headquarters on Capitol Hill a stone’s throw from Senate office buildings. Instead, it was located in a ramshackle old wooden building on the dicey borderline of the safe part of Capitol Hill.

I was interviewed by a trim, mid-30ish guy who was immaculately coiffed and, despite the brutally hot Washington summer day, wearing a formal vest from a three-piece suit. His vibe that day left no doubt that he was conferring a celestial blessing by meeting with me.

He beamed as he sat in a swivel chair on the other side of a broad table. After the standard pleasantries, he looked down his nose and picked up the resume and stack of clips I had sent the previous week.

“Hmmm…“ he said almost absent-mindedly, as if talking to himself. “You’ve been published in New York Times…Chicago Tribune…Boston Globe…Washinton Star…Nice.”

When his skimming reached the bottom of the page, his face brightened with a triumphal gloat. “Oh!” he happily announced. A pregnant pause was followed by judicious raising of eyebrows to signify astonishment, if not shock and horror.

“I see that you didn’t finish college.”

“Yep,” I replied.

He tilted back in his chair, crossed his arms, and, with a condescending smirk, solemnly announced: “Mr. Bovard, you’ve got to pay your dues.”

I struggled mightily to repress a Cheshire cat grin.

“Go back to college, finish your degree, and then contact us after you graduate,” he announced as if he were bestowing the most valuable advice I’d ever receive.

I burst out laughing but preserved a modicum of decorum by not falling out of my chair. The “interview” ended moments later. If employers fixated on degrees and nothing else, I was as happy to ax them from my list as they were to disqualify me.

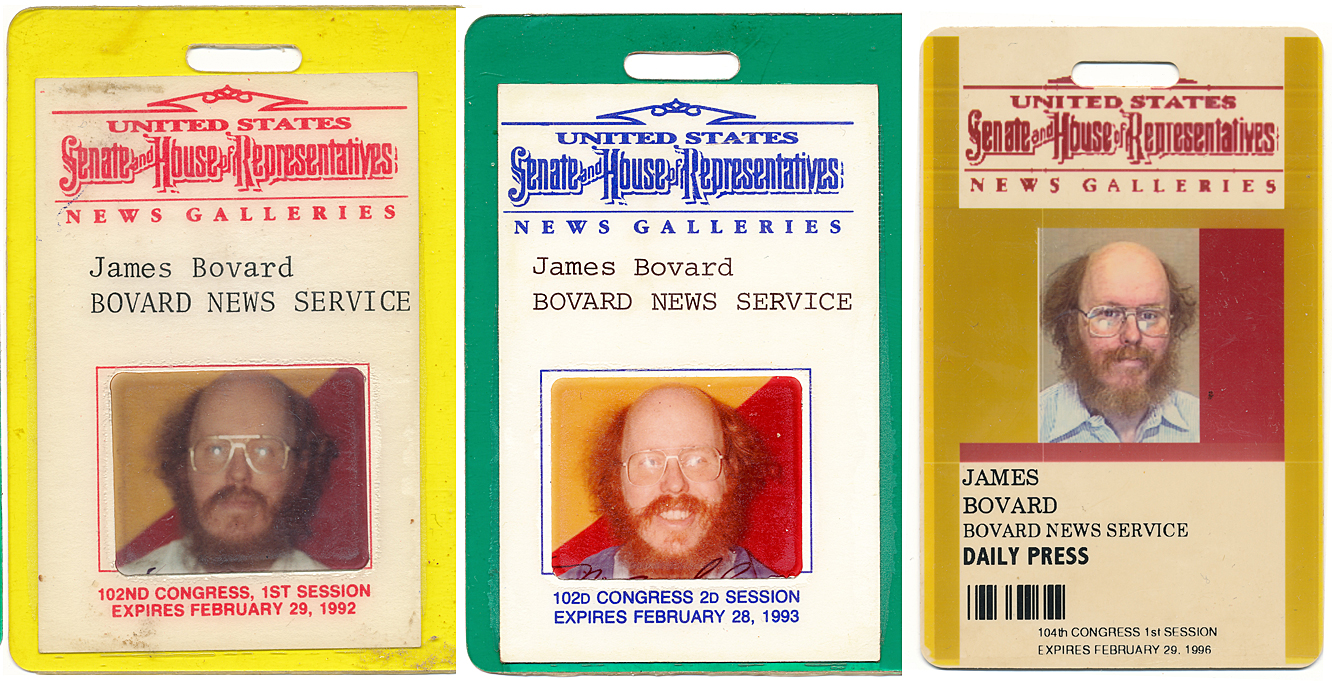

Four years later, I was writing regularly for Wall Street Journal, Reader’s Digest, USA Today, Washington Times and other newspapers. I was often covering hearings and other events on Capitol Hill. When I sought a press pass from the Senate Press Gallery as a freelance writer, I was given a couple 90-day temporary passes. When I returned for an extension, I ended up palavering with a couple Senate staffers who helped run the gallery. They were friendly guys with none of the officiousness that tainted other Hill staffers.

“We don’t give full-year passes to freelancers,” declared the older guy. “This would be a lot easier if you had a permanent affiliation.”

“Yep, I understand,” I shrugged.

His colleague had been nodding his head and then added, “If instead of being a freelance writer, if you were ‘Bovard News Service’….

“HEY!” I responded. “I am Bovard News Service!”

We shared a hearty laugh and for the next twenty years, I received annual Senate Press Gallery passes for Bovard News Service.

That press pass provided access to the Senate and House press galleries overlooking the congressional chambers. I spent many hours in the front row overlooking floor debates and colloquies, especially on topics on which I had closely followed and written.

At first, I was stunned by the pervasive falsehoods I heard from both political parties. But studying the eyes, movements, and vibe of veteran members of Congress, I soon realized that the Capitol was a Twilight Zone where facts and truth were simply irrelevant. Almost no one showed a speck of remorse or bad conscience regardless of their howlers. They weren’t lying: they were simply talking to their personal or party’s advantage. Words were simply tokens that congressmen played to seize power, burnish their image, or boost spending for a pet cause. When politicians contradicted themselves a few minutes or days later, it didn’t matter; that was irrelevant compared to legislative victories. The longer a person “served” in Congress, the more immune they became to both reality and decency.

Congressional debates often resembled a transcript from a village idiot convention. During battles over the 1990 farm bill, several congressmen characterized proposals to end handouts to big farmers as suspiciously akin to communism. Rep. Robin Tallon (D-SC), warned, “We do not have to imagine what life would be like without a responsible farm program. We need only look to the Soviet Union where people will wait in line for hours in hopes that they can buy a small portion of beef or bread.” Rep. Pat Roberts (R-KS) seconded the alarm: “This effort to end participation of our most successful farmers and investors in the farm programs sounds a lot like the way the Poles and Russians organized their agricultural policy before the Berlin Wall came down.” Communism was a bad thing, and ending farm subsidies was a bad thing, so anyone who advocated ending subsidies was a communist. Reducing political control over agriculture was the worst kind of tyranny. Those gems of logic sparked a Wall Street Journal piece titled, “How to Think Like a Congressman.”

In prior eras, the notion that politicians are untrustworthy rascals was part of American folklore. As Russell Baker, The New York Times Senate correspondent, lamented in 1962, “I spend my life sitting on marble floors, waiting for somebody to come out [of closed congressional hearings] and lie to me.” In a different era, Baker’s candor earned him a Times columnist spot.

But somewhere along the line, many or most Washington journalists lost their radar for government BS. The percentage of J-school grads became higher in Washington with each decade. Many of them were proud to write “The Government Told Me So” stories. Did the new cadres lose their instinctive skepticism in journalism school? I got some of my best stories in ways that would horrify journalism professors, including “How I Robbed the World Bank” and “Heisting the Secret U.S. Tariff Code.”

The changing standards were exemplified by Mary Lou Forbes, a Washington Times commentary editor who I wrote more than a hundred pieces for over twenty-five years. She was a sweet lady who was tough as nails. She won a Pulitzer Prize in 1959 for her coverage of Virginia desegregation battles while she worked at The Washington Star. In one of the final phone conversations we had before her death from cancer, she went on a tear about how she disliked the word “journalist.” She explained, “In my day, we were reporters”—a term she liked because it had zero pretension. In my R.I.P. blog tribute to her, I wrote that “her rare combination of grace, toughness, and sound judgment will not soon be equaled in Washington.” She never asked me whether I had a college degree, and I didn’t realize until checking recently that she had been a math major before she dropped out of the University of Maryland in the 1940s.

I view “journalist” as an occupation, not as a title or an honorific. In daily life, the term is simply another one of my flags of convenience—along with writer, reporter, investigator, muckraker, hooligan, policy analyst, author, and “innocent-looking bystander.”

But the push for professionalization of journalism snags Assange and brigades of citizen journalists who expose official wrongdoing. A 2022 survey found almost half of American television journalists favor government licensing for their occupation. This is indicative of how those journalists fail to understand either the nature of government or of journalism. Or perhaps they believe that kowtowing to officialdom is the high road to truth—or at least the greatest glory they will ever achieve? Perhaps this is what happens when the press corps becomes full of journalism majors with no clue on the long history of oppression.

Licensing knuckleheads have an ally in Oklahoma Sen. Nathan Dahm, who recently proposed the “Common Sense Freedom of Press Control Act.” Dahm, the state chairman of the Republican Party from Broken Arrow, Oklahoma, touted a bill to compel journalists to become licensed, comply with criminal background checks, complete a “propaganda-free” training course approved by politicians or their appointees, and submit to quarterly drug tests. Regrettably, there are no current proposals to require state legislators or members of Congress to take regular IQ tests.

The First Amendment was never entitled to be a class privilege of the media establishment. Squabbles over who is a journalist distract from the grave peril of government oppression for anyone who offends Uncle Sam. After Julian Assange was hit by a federal indictment, a New York Times editorial declared that the charges were “aimed straight at the heart of the First Amendment” and would have a “chilling effect on American journalism as it has been practiced for generations.” Assange and Wikileaks provided a huge booster shot to democracy by alerting Americans to how they had been deceived and misgoverned.

Assange’s courage and credibility matter far more than his credentials. But the fight over his fate is taking place in a time of growing threats to freedom of the press. 55% of American adults support government suppression of “false information,” even though only 20% trust the government. Relying on dishonest officials to eradicate “false information” is not the height of prudence. A September 2023 poll revealed that almost half of Democrats believed that free speech should be legal “only under certain circumstances.” Support for censorship is stronger among young folks—a grim harbinger for American freedom. The peril is compounded because The New York Times and Washington Post have jumped on the Disinformation Suppression Bandwagon.

At a time of growing perils, journalists, writers, muckrakers, and hooligans need to make common cause to resist the latest wave of repression. In this battle for the survival of freedom, there is even room for Hokie dropouts. But any journalist who favors government licensing of their occupation deserves all the tar and feathers we can find.