“The spirit of the times may alter, will alter. Our rulers will become corrupt, our people careless. A single zealot may become persecutor, and better men be his victims. It can never be too often repeated that the time for fixing every essential right, on a legal basis, is while our rulers are honest, ourselves united. From the conclusion of this war we shall be going downhill. It will not then be necessary to resort every moment to the people for support. They will be forgotten, therefore, and their rights disregarded. They will forget themselves in the sole faculty of making money, and will never think of uniting to effect a due respect for their rights. The shackles, therefore, which shall not be knocked off at the conclusion of this war, will be heavier and heavier, till our rights shall revive or expire in a convulsion.”- Thomas Jefferson

Throughout the COVID-19 Dumpster Fire™, there has been scholarship addressing all manner of topics. Having written or co-written articles critical of the response to the pandemic, it strikes me that some of the responses to the pandemic have been overwrought, heavy-handed, unscientific, and politically-motivated. Is it not proof enough that Democratic governors and the Republican governors from various regions all over the U.S. employ startlingly different approaches? Science does not care which animal-shaped idol is on the governor’s flag.

The larger questions—the efficacy of lockdowns; the necessity for vaccination mandates; the utility of sanitization of surfaces; and, the effectiveness of social distancing—are each worthy of a separate article. This article represents an attempt to get a few points regarding what should be a rather small and mundane subject out in the open. That subject is masks. Do they provide protection of any type, and if so, how? Is there any historical or scientific basis for thinking masks provide protection against a respiratory virus? Are they really little more than a virtue signal? Is this the first time they have been used this way?

At a glance…

- Data: No data, available and collected via Randomized Clinical Trials (RCTs), and evaluated via a clinical end-point, masks as effective in preventing infection by or transmission of the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

- History: Mask mandates in the United States date back at least 100 years, at least to the Spanish Epidemic of 1918. As such, ample time has passed to justify positive effects from masking via experimentation, if it were possible to do so.

- Engineering: A basic performance analysis—wherein the key features and requirements of a mask as either a semi-permeable or impermeable membrane are analyzed—shows that not only do masks not accomplish anything positive, but also that they likely cannot.

Am I Qualified to Ask These Questions?

As much as one detests the implication that only people who are qualified can speak on subjects such as these, I feel compelled to offer just a bit of background. My training is in engineering generally and biomedical engineering specifically. I spent 17 years in regulated medical device design and development. During my early career, working for major corporations which marketed regulated medical devices, I had the good fortune to lead design teams in a variety of realms, and to secure a patent or two along the way.

At the culmination of that stage of my engineering career, I had moved beyond hardware design, and into data analysis, developing statistical experiments for determining if a specific diagnostic test performed at a level equal to, better than, or (unfortunately) worse than, the existing market standard. Thereafter, I was analyzing and reporting upon the results of these tests, typically for submission for the FDA, to support applications for sale for those diagnostic tests. The goal was not simply determining if our blood analyzer was delivering an incorrect answer, but also, determining what portion of that complex system was the culprit, in the case of an unexpected result. This is the very definition of systems engineering in that realm, and hopefully applicable to the mask versus no-mask debate.

A further bit of disclosure is necessary. When the mask mandates first came out, I was, like many people, hopeful that they would help. I wore my mask routinely, and I invested in quality masks for both my immediate family and my parents. I saw no reason to push back on the idea that masking was “a small ask” or that “masking up” would be beneficial in the long term. That said, I had done no analysis of the justifications. I had done no historical examination. I had not done even the most basic engineering analysis. I was, in effect, simply following orders! This article is intended to take the reader on my journey, delving into the evaluation I undertook once I began to have doubts. The journey was somewhat winding, but in some ways, it was also a straight line. At least, it seems like a straight line1I am not unaware of what Daniel Kahneman, in “Thinking, Fast and Slow,” characterizes as our (flawed) tendency to look for coherent stories and thereby convince ourselves of the inevitability of any conclusion(s) we reach. at this point! I apologize in advance. This piece is long. In order to convey the whole journey, that was unavoidable.

Initial Chinks in the Armor?

My attempts to convince myself of the efficacy of masks led to the development of a nomological network of cumulative evidence2This concept was developed and presented by Gad Saad, in “The Parasitic Mind.”, or nom-net, for short. A nom-net is based upon the examination of a wide variety of data and evidence—historical, cross-cultural, pro, con, anecdotal, scientific, and data-based—with the goal of assembling enough information that a conclusion seems both obvious and unavoidable. Worth noting that the conclusion is not made ex ante, and thereafter supported by the nom-net. Instead, a conclusion is reached after enough information has been gathered to make the conclusion inescapable.

In my quest to obtain as much information as possible on the why (or why not) of masks, I started with what I then believed to be the most appropriate source—the CDC. Traditionally, the CDC has been the national purveyor, at least in the United States, of The Science ™. As well, for better or worse, whatever the CDC recommends has generally been accepted as an article of faith. Worth noting that even though the CDC is a U.S. entity, the policies implemented in the wake of those recommendations are remarkably similar worldwide. My quest to develop the database portion of my mask-nom-net, led to the creation of a simple spreadsheet, a short excerpt of which is shown below.

| Authors / Name of Study / Publishing Journal | Type of Evidence | RCT? | Conclusion / Comments |

| Rothe C, Schunk M, Sothmann P, et al. Transmission of 2019-nCoV Infection from an Asymptomatic Contact in Germany. The New England journal of medicine. 2020;382 (10):970-971. PMID: 32003551 | None. | No | This study is not about masks in any way. The point of the CDC citing this study, ostensibly, is to show that since asymptomatic people can spread the virus, everyone should be masked? Just guessing… |

| Zou L, Ruan F, Huang M, et al. SARS-CoV-2 Viral Load in Upper Respiratory Specimens of Infected Patients. The New England journal of medicine. 2020;382 (12):1177-1179. PMID: 32074444 | None. | No | This study is not about masks in any way. |

| Pan X, Chen D, Xia Y, et al. Asymptomatic cases in a family cluster with SARS-CoV-2 infection. The Lancet Infectious diseases. 2020. PMID: 32087116 | None. | No | This study is not about masks in any way. |

Those headings are pretty self-explanatory. At that time, around the middle of October, 2020, the CDC had nineteen (19) or so references on their website, ostensibly providing evidence of the usefulness of masks. The excerpt above shows the first three (3) citations from that timeframe. My intent was to read as many of those studies as possible, and glean insight into why the CDC had concluded that masks were an important NPI in the fight against COVID-19. Of those initial 19 citations, nine (9) of them—and additional six (6) on top of those listed above—fell into the same trap. They were not about masking. Masking was not mentioned in those 9 papers, at any point. In fact, all of them fit the same general pattern. They were, essentially, a study of what happened when a Chinese researcher, or team of researchers, followed a family, with one or more members who ostensibly had COVID-19, home from the airport. (No, I am not kidding.)

Of the remaining studies cited at that time, not one of them—not a single one—was the result of a randomized clinical trial (RCT) with a clinical endpoint, nor did any of them provide direct evidence of the efficacy of masks. Direct evidence is evidence that the use of a mask resulted in less infection. Indirect evidence is evidence that the mask resulted in less of something else, such as droplet flow. In order for indirect evidence to be legitimately probative, that evidence must be a valid proxy. Consider: If there is less droplet flow, yet no change in rate of infection, one could argue that particular proxy is worthless. One does not need to be a crack detective to notice that mask justifications are almost universally based upon proxies versus direct evidence.

By this time, I hope the reader is scratching his or her head, wondering why so few of these supposedly citable studies used the “gold standard” in clinical research, the RCT. Why would such studies be found in a list of references that supposedly justified universal masking? I wondered as well. (Interestingly, many, if not most, of the studies that show masks do not work are, in fact, RCTs with clinical endpoints. More on that later.) Was I missing something? It turns out that I was. In October of 2020, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine held a (virtual) workshop with the title, “Airborne Transmission of SARS-CoV-2.” Directly from the proceedings of the workshop, we find this description of its purpose:

The workshop was organized by the Environmental Health Matters Initiative (EHMI) to address the state of the science (what we know, what we need to know, and what research is needed) around these four critical questions:

-

What size aerosol particles and droplets are generated by people and how do they spread in air?

-

Which size aerosol particles and droplets are infectious and for how long?

-

What behavioral and environmental factors determine personal exposure to SARS-CoV-2?

-

What do we know about the relationship between infectious dose and disease for airborne SARS-CoV-2?

An interesting understanding was shared at this workshop, by Julian Tang, University of Leicester, who was a staunch proponent of masking. He and another researcher, Ben Cowling, University of Hong Kong, cautioned the attendees against attempting to use an RCT, which was then currently pending, to prove the efficacy of masks. They reasoned that it is difficult to measure an effect with masking, and any negative results in such “official” trials could be misinterpreted. Instead, they suggested that mechanistic indications of mask effectives—reduction in droplets reaching a target, for example—was superior to clinical endpoints. For me, this was an amazing statement.

Here were prominent researchers, suggesting that one should assume that mechanisms that reduce a surrogate marker are useful in making policy decisions, in lieu of actual determinations of whether or not a mask wearer became infected at a lower rate than a non-mask-wearer. Just as stark is the positioning of the “four critical questions” around which the workshop was constructed. Most of them also use something that is supposed to illustrate likelihood of infection with SARS-CoV-2, but which is still only an assumption. The relevant question would seem to be, “Does wearing a mask make the wearer less likely to be infected by SARS-CoV-2?” If droplet flow or whatever proxy is higher or lower, but acquiring infection by the virus—the clinical endpoint—is unaffected, measuring that proxy is, with apology for being direct, worthless theater.

Having sufficiently examined the key source of pro-mask literature—at least at that time—I went on to develop a similar matrix, except with data and studies which decried the use of masks. An excerpt of that matrix is below:

| Authors / Name of Study / Publishing Journal | Type of Evidence | RCT? | Conclusion / Comments |

| MacIntyre, Seale, Dung, et.al., A cluster randomised (sic) trial of cloth masks compared with medical masks in healthcare workers. BMJ Open, 2015 | Clinical Endpoint. | Yes | This study found that wearers of cloth masks experienced higher rates of infection.

“…as a precautionary measure, cloth masks should not be recommended for [health care workers] HCWs…” |

| Unmasking the surgeons: the evidence base behind the use of facemasks in surgery. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine | Clinical Endpoint. | No | This study found that the rate of surgical site infection (SSI) was unaffected by the use of surgical masks. |

| Surgical mask to prevent influenza transmission in households: a cluster randomized trial. PLoS One | Clinical Endpoint. | Yes | “In various sensitivity analyses, we did not identify any trend in the results suggesting the effectiveness of facemasks.” |

| Use of surgical face masks to reduce the incidence of the common cold. American Journal of Infection Control | Clinical Endpoint. | Yes | “Face mask use in health care workers has not been demonstrated to provide benefit in terms of cold symptoms or getting colds. A larger study is needed to definitively establish noninferiority of no mask use.” |

The careful reader will, almost immediately, make a couple of relevant observations about this table. First, the bulk of the results are RCTs. Secondly, the evidence evaluated was a clinical endpoint, i.e., did the wearers of masks get sick more often? That is, did the masks provide protection from the infectious agent?

As before, I only include a snippet of my entire spreadsheet table. The list of anti-mask studies is larger than the list of pro-mask studies. As well, if one additional general conclusion can be drawn about the studies used to justify masking versus the studies that decry its effectiveness, it is this. The studies used to justify masking employ proxies and/or are not randomized controlled trials; the studies that question the effectiveness of masks use clinical endpoints and are, more often than not, randomized, controlled trials. Taken in context with the admonitions of Drs. Tang and Cowling, maybe this should not be surprising, but it still surprised me. One would think, nay expect, that given time, an actual RCT, with one or more clinical endpoints, would finally answer the masking question once and for all. Maybe there had simply not been enough time? The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic is new, correct?

History Has Not Been Kind?

Some of the media messaging during the COVID Dumpster Fire™ has implied that SARS-CoV-2 is so new that many of the lessons learned over hundreds of years of immunology are not applicable. Is that true? Why not look back at how the Spanish Flu Epidemic of 1918 was handled? The next phase of the generation of my mask nom-net was looking at that history. It shocked me to see pictures, such as the ones below, in various Internet archives.

Baseball Umpire, Catcher, and Batter, Masked-Up, 1918

Children, Masked-Up, 1918

Trolley Patrons, Street Cleaners, Masked-Up, 1918

A few points jump out about these pictures. One, they show people wearing cloth masks, much like the cloth masks worn over the last couple years. Two, these pictures are from over 100 years ago. The wearers were responding to a mask mandate of that time, much like the mask mandate(s) during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. The fact that mandates were used, both then and now, to force behavior upon the citizenry is not unusual. What strikes me as telling is that in the more than one hundred years between 1918 and now, no one has produced a definitive study illustrating that such mandates are anything but theater. It would seem almost obvious that given such a significant passage of time, ample evidence could be gathered showing:

- Mask mandates of 1918 were helpful in slowing the progression across the population;

- Mandating masks has obvious benefits with respect to respiratory viruses;

- Therefore, mandates should be used against COVID-19, another respiratory infection.

Instead, as illustrated by the data portion of my mask nom-net, we still currently have almost nothing but proxy-based tests, using mechanistic indications, which have, at best, a tenuous relationship to clinical endpoints. (I will refrain from commenting on the lunacy of having a baseball player, who is outside, in an athletic event, wearing a mask.) It is worth noting that I have continued to develop the data gathering portion of mask nom-net, adding data and studies to the matrices described above. For the record, no new clinical endpoint data supporting masking has appeared. What if mechanistic studies are actually sufficient? For that to be true, a basic engineering analysis should also support that assumption.

Can I Interest You in a Basic Performance Analysis?

Would an engineering analysis provide additional insight? The nearly-final phase of my mask nom-net involved performing an engineering analysis, based upon my training and understanding of flow through membranes, which is engineering 101 for a biomedical engineer like myself. From the standpoint of basic performance, there are two (2) and only two (2) functions that a face mask serves—acting as a filter (selective blockage); or acting as a barrier (complete blockage) for virus particles.

For masks to perform effectively as filters, there are essentially two (2) requirements:

- Effective filtration requires pores to trap target molecules. This is determined by, “minimum viable particle size.” Pore size in cloth masks never meets the requirement of blocking minimum particle size. Pore size, in even N95 masks, meet the requirement occasionally, depending on the virus, where sizes vary.

- Safe filtration requires that the trapped target molecules be subsequently disposed of, via sterilization or other means, after wearing. That is, the “minimum infective dose” of virus must not be able to make it through the membrane, either via pass-through, or due to and/or culturing after capture.

Given those requirements, an objective evaluation of masks as filters leads to this outcome:

As a filter, masks are insufficient, often unable to block the minimum infective dose and actually providing a medium for subsequent culturing of pathogens. Thus, in contrast to being a means to prevent virus spread, masks could actually make matters worse.

For those keeping score at home, this is exactly as indicated by the results of RCTs involving cloth masks, which fall into the filter camp, were tested via an RCT. The mask wearers got sick more often. Seems that saving possibly infectious material in a warm, moist medium on one’s face is not that good an idea after all. My analysis result above is verified by the experimental outcome via a clinical endpoint trial by someone else. Dare I say, science!

For masks to perform effectively as barriers, there are essentially three (3) requirements:

- Effective barriers must completely block the flow of virus, not only through the blocking matrix, but also around it.

- Effective barriers require a supplementary source of oxygen for the wearer, unless the barrier is designed to allow for an alternative path—as is the case for face shields—which are therefore non-mitigating for airborne pathogens. (An unfiltered, unblocked, alternative path guarantees that virus particles that are airborne and sized sufficiently to travel via aerosol—which is the most likely case for SAR-CoV-2—can simply flow around the barrier and reach the target.)

- Safely blocked trapped target molecules must be subsequently disposed of, via sterilization or other means, after wearing. That is, the “minimum infective dose” of virus must not be saved or stored on either side of the blocking membrane, or cultured after capture.

Given those requirements, an objective evaluation of masks as barriers leads to this outcome:

As a barrier, masks are insufficient, and actually concentrate the flow of virus-laden air, via other routes and flows—such as plumes—to the user. If the barrier is against the face, then it becomes a medium for subsequent culturing of an array of microbial matter, versus a means to prevent virus spread. If the blocking matrix does capture virus particles on the outside, then subsequent handling of the blocking matrix could transfer those captured virus particles to the user via other paths.

Based upon a simple performance analysis, masks cannot be considered as a viable NPI for the spread of a respiratory virus. The multitude of charts and graphs from all over the world, which illustrate at best, no relationship, and all too often, a negative relationship between mask mandates and COVID-19 prevalence—regardless of rubric—is further testament.

What About That German Study?

Over the 18+ months between the “two weeks to flatten the curve” promotions and the publish date of this piece, in early 2022, many a blogger, Twitter poster, and armchair pundit has opined on the pros and cons of masking. Some of them have produced and provided a multitude of charts, showing that the implementation of mask mandates provided absolutely no positive relationship to cases, hospitalizations, or deaths. In fact, those COVID-19 metrics—cases, hospitalizations, deaths—typically went up despite the mask mandates. Not a single study—at least that has been cited by the CDC or any other official body—has shown otherwise.

Well, that is not quite true. One study did make that claim. Since that study is indicative of the type of half-assery I expect from the Cult of Mask, I will examine it in full, just before my conclusion. Call it a parting shot. If you have read this far, you deserve a bit of dessert to cleanse your palate. As the coup-de-gras for my mask nom-net, I present a complete analysis–and take-down–of that German study.

The title of the paper in question is, “Face masks considerably reduce COVID-19 cases in Germany.” The abstract of the paper states, “We use the synthetic control method to analyze the effect of face masks on the spread of COVID-19 in Germany. Our identification approach exploits regional variation in the point in time when wearing of face masks became mandatory in public transport and shops. Depending on the region we consider, we find that face masks reduced the number of newly registered severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infections between 15% and 75% over a period of 20 days after their mandatory introduction. Assessing the credibility of the various estimates, we conclude that face masks reduce the daily growth rate of reported infections by around 47%.”

A tell-tale sign of cherry-picked data in a study is the inclusion of data from n-days in combination with what the authors describe as a “synthetic control method.” (What?) This study design necessitates several (obvious, to me) questions:

- How did the study authors decide upon that particular number of days;

- How might the results have been different for 25 days, or 15 days, or an altogether different 20-day period?

- Why is it necessary to limit the scope of the study period, assuming that masking is generally effective?

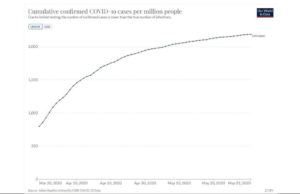

A closer examination of the data used for the German paper, which is publicly available, via COVID-19 Data Explorer – Our World in Data, illustrates the points above. The chart below entitled, “Study Period Shown in German Paper, Mitze, et.al.,” shows the results used to provide the ostensibly positive outcome in the paper. Sure enough, the slope of the cumulative case graphs bends down, beginning around April 6 or so. Hurray! Masks work! End of story?

Study Period Shown in German Paper, Mitze, and et.al.

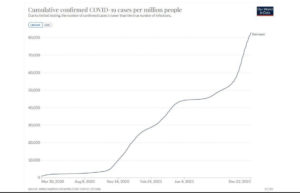

Not so fast, my friend! The chart below, entitled, “All Data from Germany, including Study Period Shown in German Paper, Mitze, et.al.,” includes data gathered after the study period ended. Note that only a few weeks after the study period–maybe during the time that the paper was under peer review–the performance of mask mandating seemed to change. As a result of that obvious change in performance, to say that masking was effective appears to be a stretch. That is, unless masking only worked 20 days and then resulted in absolutely the opposite effect.

All Data from Germany, including Study Period Shown in German Paper, Mitze, et.al.

The cumulative confirmed cases graph does bend down during the study period, reported by the study authors to be somewhere between March 30 and April 30, but the identical dataset illustrates a strikingly different outcome soon thereafter—almost as if the authors only selected the data range that supported their desired conclusion. Regardless of the authors’ motivations, or the reasons why the National Academy of Sciences of the United States would allow such half-assery to influence policy decisions, the conclusion fits all the previous evidence from my mask nom-net. I suspect that the Cult of Mask could use some tortured, mental gymnastics-based, unfalsifiable, logic to explain this. That caveat aside, I need no such lunacy. (Again, multiple charts like the one above, from a variety of people, show exactly the same tendency regarding mask mandates and COVID spread worldwide.)

A Conclusion Far Too Long In Coming?

So, there you have it. A long, drawn-out explanation of a fact well over 100 years in the making. My nomological network of cumulative evidence included data from both sides of the debate, historical reference, engineering analysis, and refutation of one of the widely-cited studies ostensibly supporting widespread use of masking as either a “source control” or whatever other nomenclature one uses. The use of masks as a mitigation for the spread of a respiratory virus such as SARS-CoV-2 is folly. It was always folly. Useless theater does not a useful NPI make. Masking is not a “small ask.” Masking is a useless, and frankly, maybe even dangerous, task.