This article was originally featured at The American Conservative and is republished with permission of author.

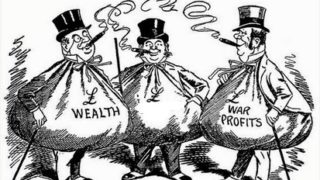

Is it unethical to profit off the mass death of your countrymen, and should something be done about it?

In a society where wealth of any origin is increasingly looked at with suspicion and envy, weapons contractors have somehow avoided the spotlight. Even domestic gunmakers have withstood more public criticism than the producers of battleships, humvees, and fighter jets.

When did a healthy skepticism of war profiteering turn into social acceptance of massive corporate structures whose material interest is destruction and who conceal their business practices through identity politics? This conditioning is the conclusion of a century-long shift in how the public perceives the munitions industry, or what came to be universally termed the “military-industrial complex.” Analyzing the history of this shift will help us determine how best to reawaken their long dormant opposition to the international racket known as war.

During the Progressive Era, with its promotion of economic regulation and “trust-busting,” the average American had already grown distrustful towards big business. Public enmity was directed at two companies in particular, J.P. Morgan and DuPont, which after the start of World War I became the poster children for war profits and undue political influence.

Founded by its namesake financier in 1871 and left in the hands of his eponymous son, J.P. Morgan & Co. had grown into one of largest investment banking firms in the world. E.I. du Pont de Nemours and Company had an even longer lineage, dating back to 1802. Managed at the time by Pierre S. du Pont (when he wasn’t busy managing General Motors as well), it was the leading chemical firm in the country.

As war spread across Europe in the late summer of 1914, Americans remained overwhelmingly predisposed to George Washington’s advice, written in his farewell address, that we should not “entangle our peace and prosperity in the toils of European ambition, rivalship, interest, humor, or caprice.” In that tradition, Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan issued an edict banning financial loans to the belligerents. This arrangement may have served Americans faithfully for over a century, but it was not satisfactory for the House of Morgan. “From August 1914 to April 1917,” writes historian Martin Horn, “while the United States was neutral, the Morgan banks worked assiduously to further the Allied cause.”

Morgan executives already had significant economic and social ties to London before the war, and these connections only grew tighter after the cannons started firing. In January 1915 the British government appointed J.P. Morgan as their official purchasing agent in the United States. The French followed suit in May. In their new capacity as the Allies’ stalking horse, J.P. Morgan would handle their foreign exchange operations and advise their political officials.

Through intricate negotiations and their position as Wall Street’s dominant bank, J.P. Morgan successfully lobbied to lift Bryan’s ban shortly after their appointment. The Great Commoner resigned from the cabinet a few months later, having correctly anticipated that Woodrow Wilson wasn’t truly committed to American neutrality.

President Wilson had been in the Morgan ambit for years, even serving on the board of their subsidiary the Mutual Life Insurance Company. It was alleged at the time, and for years after, that the House of Morgan pressured the administration to intervene on the side of the Allies to protect its financial investments. Despite numerous indications, such as local straw polls, private letters, and telegrams to Congress, that a majority of Americans continued to oppose intervention in Europe, the vote for war was overwhelming: 373 to 50 in the House of Representatives, 82 to 6 in the Senate. On the eve of the vote, Sen. George W. Norris, Nebraska’s stalwart progressive Republican, angrily declared that “we are about to put the dollar sign upon the American flag.”

Wall Street did not share Norris’ trepidation about the war declaration. According to the New York Times, “Wall Street was bright with the Stars and Stripes floating from banks and brokerage houses. Figuratively, the street gave a concerted sigh of relief.”

As doughboys landed in France, J.P. Morgan felt reassured that its loans would be repaid by a victorious British government. It was said the son made more money in two years than his father had in his entire life. And weapon manufacturers saw their profit margins skyrocket like never before. The DuPont company provided 40 percent of the propellant powder used by the Allies over the course of the war; its stock price jumped from $20 to $1,000 a share. A study of major military suppliers conducted by the U.S. Treasury Department found that aggregate corporate net income was $4.7 billion in 1913 and almost doubled to $8 billion in 1917.

Even before U.S. entry into the war, there was an attempt to place a cap on these increases. The Revenue Act of 1916 placed a special tax on munitions, the first excess profits tax in American history. For every pound of gunpowder, dynamite, or nitroglycerin, manufacturers would pay two cents to the federal government. DuPont complained that it was a personal tax, as it ended up paying 90 percent of the money collected from it during the war.

For some representatives, this penalty wasn’t nearly high enough. Sen. Hiram Johnson of California, former governor and Theodore Roosevelt’s 1912 running mate, had voted for the war but thought those “who coin the blood of war” and “make swollen war profits” should pay the cost. He proposed an 80 percent war profits tax to kneecap the likes of DuPont and Bethlehem Steel; the measure failed 62 to 17 in the Senate. Furious, Johnson referred to his colleagues as “dollar patriots, who so vociferously shout for the blood of the land but who nevertheless believe war to be a period when great profits should be made by a few.”

The guns went silent in November 1918 and World War I formally concluded the next year with the Treaty of Versailles. Great Britain kept its empire, Germany lay prostrate, and weapons contractors found themselves significantly richer than they were just four years earlier. But the American people could not pinpoint what they had gained from crossing the Atlantic, aside from 117,000 dead doughboys, unpaid war debt, and the Spanish flu.

From the costs of war grew the pervasive suspicion that the United States had fought not to make the world safe for democracy, but to make the world safe for shareholders. The premise took its complete form in the 1934 bestseller, The Merchants of Death. Written by University of Chicago instructor Helmuth C. Engelbrecht and journalist Frank C. Hanighen—future cofounder of the conservative weekly Human Events—it was an instant hit and became a book of the month club selection.

Despite its provocative title, the book is an even-tempered exposé of weapons manufacturers, including their business practices, biographical chapters on half a dozen American and European firms, and an analysis of their behavior and profits during World War I. While explicitly denying that munitions makers were the sole cause of American participation in the war, the authors do conclude that “the rise and development of the arms merchants reveals them as a growing menace to world peace.”

Americans of all walks of life agreed. The same year Merchants of Death was published, 94,000 American farmers signed a petition in opposition to increased armaments. Fifty thousand veterans paraded through Washington on April 6, 1935, in a march for peace.

Marine Major General Smedley Butler, two-time Medal of Honor winner, joined the brouhaha with his 1935 book War Is a Racket. A veteran of 130 battles on three continents, Butler claimed in a simultaneously published magazine article that he had been “a high class muscle man for Big Business, for Wall Street and the bankers. In short, I was a racketeer; a gangster for capitalism.”

By the mid-1930s, the Merchants of Death thesis was accepted to varying degrees by the Veterans of Foreign Wars, the American Federation of Labor, the National Grange, the Hearst newspaper chain, and the National Education Association.

Popular sentiment had its intended effect. Recounts historian Matthew W. Coulter: “The mounting criticism and public pressure drew attention from Du Pont officials, who in May [1934] ceased discussions with European gunpowder producers because ‘a formal agreement among manufacturers would cause the loudest and most violent criticism and put us in a very disagreeable position. We would be accused of joining together to foment wars, increase armament, etc.’”

The stage was set for a small group of dedicated activists and lawmakers to turn an all-encompassing antiwar climate into permanent policy and actionable reform. Their work would begin with further disclosures about the munitions industry.

Dorothy Detzer had served as the executive secretary of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom since 1924, a position previously held by the organization’s founder, Jane Addams. An ideological pacifist, Detzer had been lobbying Congress to investigate the munitions industry for years.

Riding the growing wave of public indignation, Detzer met privately with Sen. George Norris. Although supportive, he felt he was too old to lead such an undertaking. The two methodically went through a list of all 96 U.S. senators, crossing off names as they went. When they finished, only one man was left: Gerald Nye.

“Gerald Nye was a Republican U.S. Senator from North Dakota. He was a La Follette Republican…populist, anti-monopoly, anti-corporate, [but] he was also a nationalist, America First, patriotic,” explains Professor Jeff Taylor of Dordt University in an interview with The American Conservative. Taylor also serves as an Iowa state senator. “He was derided by the metropolitan press in the East as this country bumpkin from out in the sticks of North Dakota but he was a smart guy and a very principled guy.”

He was also a hothead. Nye was an inflammatory speaker who tended to personalize politics and overstate his arguments. Norris, aware of Nye’s peccadillos, excused them as “the rashness of enthusiasm.”

Although he initially turned down Detzer’s entreaties, Nye eventually accepted the role that had been chosen for him, and he filled it with gusto. “The time is coming when there will be a realization of what monkeys the munition makers can make of the otherwise intelligent people of America,” the brash North Dakotan told the press.

What would be dubbed the Nye Committee was created through old fashioned Washington wheeling and dealing. Congress was set to approve the Vinson-Trammel naval shipbuilding bill to appropriate $470 million for the construction of 102 new ships, making the U.S. Navy the equal of the British fleet. Nye, leading a minority in opposition to the bill, introduced an amendment which would cap profits as 8 percent of the cost of each warship and mandate that half of them be built in government shipyards. To placate and compel him to withdraw his amendment, the Senate voted to create a formal committee to investigate arms manufacturers on April 12, 1934.

This maneuver showed Nye to be a “skillful and shrewd parliamentary tactician,” in Detzer’s words. For her efforts she was permitted to select the committee’s chief investigator and join its staff. Her choice was Stephen Raushenbush, son of the Social Gospel theologian and a true believer in the Merchants of Death thesis. Journalist John T. Flynn signed on as a member of the committee’s advisory counsel.

“The mere hint of an investigation had met with wide acclaim,” recalled Secretary of State Cordell Hull in his memoirs. Seeking support in the Midwest for his domestic programs, President Franklin Roosevelt gave his public blessing to the investigation. Nye was joined by six other senators who promptly voted him chairman.

The Special Committee on Investigation of the Munitions Industry was the first of its kind. Perfunctory commissions had been appointed before, but never anything with the force of law to compel arms manufacturers into the limelight. Historian Stuart D. Brandes referred to the committee as “the most earnest and influential political investigation of the first half of the twentieth century.”

In its less than two years of life, the Nye Committee held 93 hearings and called more than 200 witnesses to testify. These included personages as prominent as J.P. “Jack” Morgan, Pierre S. du Pont and his brothers, and former Senate Majority Leader James E. Watson.

Working with limited funds and a minuscule staff, the committee searched the records of major arms and munitions firms for skulduggery—and they found it. Criminal or unethical actions included bribery of foreign officials (primarily in South America), lobbying the U.S. government to obtain foreign sales, selling weapons to both sides of international disputes, and covert undermining of disarmament conferences.

“The committee listened daily to men striving to defend acts which found them nothing more than international racketeers, bent upon gaining profit through a game of arming the world to fight itself,” Nye declared in an October 1934 radio address.

To rein in the munitions industry and clamp down on war profits the committee recommended price controls, the transfer of Navy shipyards out of private hands, and higher industrial taxes. Nye suggested that upon a declaration of war by Congress, taxes on annual income under $10,000 should automatically be doubled while higher incomes should be taxed at 98 percent. “Do that and then observe the number of jingoists diminish,” he said. If such policies were ever enacted, wrote The Nation magazine, “Business men would become our leading pacifists.”

Manufacturers were not thrilled at this prospect, to say the least. “Private industry should be aided and encouraged in time of war and in my opinion should not be subject to conscription the same as manpower,” testified a smiling Eugene G. Grace, president of both Bethlehem Steel Corporation and its subsidiary Bethlehem Shipbuilding Corporation. “The incentive method of compensation, subject to limitation, is just as necessary in time of war as in peace.” Over two years, 1917 to 1918, Grace personally pocketed $2,961,000 in bonuses on top of his $12,000 annual salary as president.

Explosive hearings and Nye’s provocative pronouncements (“women and children who did lose their lives were, in effect, camouflage for covering up shipments of munitions of war”) made the committee’s findings headline news going into 1936. That winter, however, Nye dug deeper than his political beneficiaries were willing to tolerate.

In a major attack on Woodrow Wilson—dead almost twelve years—Nye accused the president and Secretary of State Robert Lansing—dead over seven years—of having withheld critical information from Congress about post-war plans and secret treaties among the Allies.

The reaction from “old-line Democrats, the lovers of Woodrow Wilson” as they were characterized by the New York Times, was fierce. Senator Tom Connally of Texas labeled Nye “a historical ghoul, to desecrate the sacred resting place of the honored dead.” Seventy-eight-year-old Carter Glass of Virginia, defending Wilson’s idealistic aims, beat his knuckles on his desk until they bled, with only Senate decorum preventing him from calling Nye a coward. Committee members Walter F. George of Georgia and John P. Pope of Idaho threatened to resign (although they had both ceased regularly attending hearings).

Losing the confidence of the Democratic party, which held a two-thirds majority in the Senate, and the Roosevelt administration, who saw Nye’s growing popularity among Republicans as a threat in the 1936 presidential election, Gerald Nye found his investigation cut short and defunded. Glass, who chaired the Appropriations Committee, said Nye hadn’t uncovered a “revelation worth $125,000, or even 25 cents.”

In their quest to definitively prove the Merchants of Death thesis, Nye and his allies fell short of their ultimate goal. “It would not be fair to say that the House of Morgan took us to war to save their investment in the Allies,” concluded Nye, “but the record of facts makes it altogether fair to say that these bankers were in the heart and center of a system that made our going to war inevitable.” Nye centered the blame on President Wilson’s lifting the ban on supplying credit to belligerents, which “paved and greased” the road to war.

The committee found no evidence that munitions manufacturers had more lobbyists or influence in Washington at the time of the war than any other special interest group, and searching through their files failed to prove collusion in naval contract bidding. The reality is there was almost no arms industry in the United States in 1914. Even when the committee was active in the 1930s, military contracts made up less than 1 percent of either Bethlehem Steel or DuPont company sales. In the estimation of historian Robert H. Ferrell, the Nye Committee was a “small investigation of several large topics.”

The public influence of the Nye Committee, however, was felt for years after its untimely demise. Contemporary historian Merle Curti observed, “The investigation had brought home to the reading public the idea that war preparedness was not only a racket but an ominous threat to the well-being of the plain people.”

In January 1937, almost a year after Democratic leadership suffocated Nye’s committee, Gallup found that 70 percent of Americans regretted their nation’s participation in World War I. An even higher 82 percent favored a prohibition on private companies selling munitions. Even as late as October 1939, a month after the German invasion of Poland, Gallup found that 68 percent of respondents continued to think American participation in World War I had been a mistake. Furthermore, 34 percent believed that in making its decision the United States had been the “victim of propaganda and selfish interests.”

Companies felt this acute public pressure. A Fortune magazine poll in October 1940 said that 59 percent of businessmen were hesitant to enter the defense industry. Even after the United States entered the Second World War, General Motors, fearful of postwar backlash, voluntarily offered the government large price reductions. According to GM vice chairman Donaldson Brown, this was done to “protect the Corporation against the public censure and ill will that might arise in future if it were charged that we had profiteered or made exorbitant profits in the war business.” Some smaller manufacturers followed suit.

The most significant policy change during this time was the byproduct of a more than two-decade court battle. During World War I, Bethlehem Steel had been the country’s leading shipbuilder and second biggest producer of steel. Disputes about its contracts, its level of profit, and a twisty road of arbitration led to the Supreme Court decision United States v. Bethlehem Steel in 1942. The Court ruled against the government’s argument that profit had been so excessive that it should be released from the agreement. It was decided that Bethlehem Steel was entitled to its full $25 million profit, a margin of 22 percent.

In response, Congress formally codified and empowered the secretary of each department to review and renegotiate military contracts after figures like total cost, time delays, and profit margins came into clearer view. This created the renegotiation process, which was used to full effect. As Fortune magazine reported in early 1944, “Some renegotiators have developed very direct questioning techniques. They may ask the contractor, ‘How big a profit are you prepared to defend now when casualties are mounting and your neighbors’ sons are being killed?’ This gives most contractors pause.” Gerald Nye’s rhetoric lived on, even as he lost reelection that same year.

Into Nye’s chairmanship stepped a one-time haberdasher from Missouri, Harry S. Truman, who was instructed to lead a committee investigating waste, fraud, and abuse during the war. Although he had supported Nye’s efforts as a freshman senator, Truman now referred to his predecessor’s committee as “pure demagoguery.” His newfound criticism didn’t prevent him from leveling the same complaints, expounding in a February 1942 speech that “individuals and companies have made extravagant fees on defense contracts at the expense of their fellow citizens. Their greed knows no limit.”

Out of a nation of 140 million people, it would be Harry Truman who succeeded Franklin Roosevelt as president in 1945. And it would be his administration that gave birth to the monstrosity that Nye and others had been searching for in vain: the military-industrial complex.

During the Nye Committee’s hearings, it was the gunpowder mogul himself, Pierre S. du Pont, who laid out the most cogent, succinct rebuttal to the Merchants of Death thesis. The temporary nature of war, du Pont explained, made them bad markets for long-term investment. Some businesses might expand to accommodate the new demand, but wars tend to end abruptly, leaving those firms high and dry with no return on their capital. No industry can survive on war, he concluded.

But that was in 1936, a world away from where the United States stood just a decade later. With the emerging Cold War with the Soviet Union, the military budget became an invariable war budget. The National Security Act of 1947 united two subdivisions into the Department of Defense, and created the Central Intelligence Agency. A permanent bureaucracy was established along the Potomac. No longer would American wars be temporary, and there would be no more abrupt ends. Pandora’s box was opened for the perpetual profit in arms.

To put things in perspective, Institute for Policy Studies cofounder Richard J. Barnet relates in his book The Economy of Death a story from the late 1930s of a chemist applying for work in the U.S. Department of the Navy and being rejected on the grounds that the department already had one. Fast forward thirty years to when Barnet was writing in 1969, and half of all scientists and engineers in the United States worked either directly or indirectly for the Pentagon. Economist Robert L. Heilbroner called the American system of military production “the largest planned economy outside the Soviet Union.”

While the interwar period saw disarmament conferences, the proliferation of peace groups, and mass demonstrations against war, the postwar era saw a population too fearful of the communist menace to make a fuss about munition profits. By the late 1950s, after Sputnik reached the atmosphere and candidates spoke about a phony “Missile Gap,” public opinion was heavily skewed towards higher military spending. Americans believed the boasts of Premier Krushchev that the Soviet Union would assert its dominance over space, science, and the skies.

And there stood a president who felt he was losing control over the situation.

Dwight D. Eisenhower, as Supreme Allied Commander during World War II and commander in chief for eight years, was more intimately familiar with the operations of the Pentagon, its influence, and its relationship with weapons contractors than any other living person. In 1930 he had even served as chief military aide on President Hoover’s War Policies Commission, a toothless endeavor to correct and improve on the country’s military performance before the next war (including limiting profiteering).

As president he had used his stature to end active combat in Korea, temper the Suez Crisis, and even cut the conventional military budget (while increasing spending on nuclear weapons). Privately he worried how a future president, lacking his experience, would be bullied by the generals. “God help this country when we have a man sitting at this desk who doesn’t know as much about the military as I do,” Eisenhower confided to General Andrew Goodpaster.

On January 17, 1961, Eisenhower gave his nationally televised farewell address from the Oval Office. “Until the latest of our world conflicts, the United States had no armaments industry,” he said, in contrast with the “permanent armaments industry of vast proportions” that had been created in the previous fifteen years.

His warning was dire:

This conjunction of an immense military establishment and a large arms industry is new in the American experience. The total influence—economic, political, even spiritual—is felt in every city, every State house, every office of the Federal government. We recognize the imperative need for this development. Yet we must not fail to comprehend its grave implications. Our toil, resources and livelihood are all involved; so is the very structure of our society.

In the councils of government, we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex. The potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power exists and will persist.

Eisenhower was the first public figure to use the term “military-industrial complex,” a phrase that has become the standard for describing the sprawling, integrated system of corporate power, military brass, and government bureaucracy that allows northern Virginians to make big salaries while working twenty hour weeks.

It would be a few years until “military-industrial complex” entered the common vernacular, when it was picked up by the anti–Vietnam War left. In the 1960s, the disparity between the size of the military’s budget and the paltriness of its results in Southeast Asia became too stark to ignore. The Kennedy and Johnson administrations spent half a trillion dollars on defense, equal to the amount spent from 1945 to 1960. This didn’t bring Westmoreland any closer to stomping out the Vietcong, but it did increase the value of military contracts awarded to Johnson’s home state of Texas by a factor of three and a half.

The Vietnam War led to a groundswell of outrage against many domestic institutions. People particularly distraught with the behavior and performance of weapons contractors found their champion in Senator William Proxmire, Democrat of Wisconsin.

“He was kind of a gadfly and a protector of taxpayers’ trust,” recalls William Hartung, director of the Arms and Security Program at the Center for International Policy. “He was very into government ethics. He took little to no campaign contributions, he did a lot of campaigning just by walking his district. He was kind of ascetic, in some ways, certainly not open to things like gifts from special interests or anything like that.”

“He worked with whistleblowers in the Pentagon to expose the cost overruns on the C-5A transport plane, which was a Lockheed production. And that was one of the bigger, probably going back to the war profiteering days, one of the bigger exposés of corporate malfeasance in the military sector,” Hartung adds.

Proxmire was the archnemesis of the Lockheed Corporation, already the largest military contractor in the United States. He led the opposition to the company’s bailout by the federal government in 1971, a measure that only passed the Senate with a tie-breaking vote by the vice president. Despite the loss, Proxmire did shepherd the passage of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act of 1977, outlawing the munitions industry’s bribery of foreign officials that had been discovered in the 1930s.

Despite his ability to build coalitions against the most egregious examples of profligacy, Proxmire’s fight against the military-industrial complex was a lonely one. His Golden Fleece Award, which he would hand out monthly to the most wasteful government programs, was an entertaining gimmick, but his efforts lacked both the enthusiasm among the public and the supportive partnership of his colleagues that propelled the Nye Committee’s investigative power.

As was to be expected, the behemoth that had been fed a steady diet of public subsidies for 45 years didn’t dissolve alongside the Soviet Union. Instead it consolidated, notably with the mergers of the Northrop and Grumman corporations in 1994 and of Lockheed and Martin Marietta in 1995. By 2001, the new millennium began with five companies holding a majority of Pentagon contracts: Lockheed Martin, Raytheon, General Dynamics, Boeing, and Northrop Grumman.

The Global War on Terror has proved a bonanza for the industry. “I am a believer in an adequate national defense,” Senator Nye said in 1934. “I do not believe in preparing, as we are today, to go to all quarters of the earth to wage war.” He hadn’t seen anything yet.

The United States currently possesses nearly 800 military bases located in over 70 countries. In the past twenty years it has launched ground invasions of Iraq and Afghanistan, fought covert wars in Syria, Yemen, and across Africa, and conducted air wars on Libya, Pakistan, and half a dozen other countries. The monetary costs boggle the mind.

The U.S. Department of Defense “spent $14 trillion adjusted for inflation since 2001,” says Hartung. “And it went up ten years running after the September 11 attacks, which had never happened before. And now it’s hovering well above the peaks of Vietnam, or Korea, or the Reagan buildup.”

Unlike their prewar predecessors, whose portfolios were slim on military contracts, today’s companies are animals that feed solely on Pentagon chum. In 2017, arms sales represented 94 percent of Raytheon’s total revenue. Lockheed-Martin, the largest defense contractor in the world, received 88 percent of its revenue from arms sales, followed closely by Northrop Grumman at 87 percent and General Dynamics at 63 percent. The smallest is Boeing at 33 percent.

“What that produces is a scenario where public money is effectively being funneled, hundreds of billions of dollars a year into these private corporations whose number one priority is not U.S. national security. The number one priority is not even job creation. Their number one priority is profits for their shareholders,” said Eli Clifton, senior advisor at the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft. “Is it good for American security to be that dependent on essentially five companies, and is it good for the U.S. economy?”

In serving their shareholders, the military-industrial complex has been eminently successful. If you had purchased $10,000 worth of company stock in 2001, after twenty years of war in the Middle East that same stock would be worth $43,167 with Raytheon, $72,516 with General Dynamics, $107,588 with Boeing, $129,645 with Northrop Grumman, and $133,559 with Lockheed Martin.

When defense contractors win, you can trust that it’s the taxpayers who lose. Cost overruns and overcharges are not an anomaly but something that affects every part of the military-industrial complex from the most advanced missile system to the tiniest tool.

With the loss of the renegotiation process, efforts by the government to recoup these unforeseen expenses have been largely “defanged,” explains Mandy Smithberger, director of the Center for Defense Information at the Project on Government Oversight. “It’s become increasingly challenging for the government to challenge overcharges. The Department of Defense Inspector General is going to be coming out with a new report on the company Transdigm which made headlines for, in one case, charging a profit in excess of 4,000 percent. But in that case the company gave a refund but it was a voluntary refund because there really wasn’t anything they did that was illegal.”

Modern polling on the military-industrial complex is nonexistent. Americans are regularly asked about whether to increase or decrease the military budget, and occasionally even about individual arms sales to certain countries. But they are never asked the heart of the matter: whether large corporations making exuberant profits from the fighting and dying of U.S. soldiers is permissible in the first place.

Smithberger believes the lack of data is demonstrative of how much influence military contractors have over think tanks and other non-profits that conduct most of these polls. “These are rarely the questions that are asked. There is polling around general revolving door issues… but it is not an area that gets the attention it deserves,” she told TAC.

Why has the growth and influence of arms manufacturers become a niche topic? Part of the answer is that these corporations have undergone an immense public relations campaign to portray themselves as socially conscious, progressive businesses.

In response to the 2020 George Floyd riots, Northrop Grumman donated $1 million to the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, along with $728,000 in matching funds to social justice and equity organizations that its employees gave to. The company regularly receives high marks from Human Rights Watch for its promotion of LGBTQ+ inclusion in the workplace, including producing a “comprehensive transgender toolkit and education program” for its managers and employees.

Not to be outdone, General Dynamic celebrated Pride Month this year by holding an educational seminar centered around the USNS Harvey Milk, the oil replenishment tanker they’re constructing named for the assassinated San Francisco supervisor and gay rights activist.

In addition to sponsoring floats at various pride parades, Lockheed Martin has spent more than a decade trying to make its brand synonymous with LGBTQ+ acceptance. In one of its advertising videos, an employee named David tells the audience, “I’m married to a man. I’ve been at Lockheed Martin for thirteen years. And that’s who I am. And you know what, together those two things are amazing.”

Last year, Lockheed Martin sent thirteen white male senior executives to a special diversity training program to be divested of their white, male, heterosexual privilege. The executives learned that qualities like “rugged individualism,” “hard work,” “operating from principles,” and “striving towards success” are the groundwork of a racist, misogynistic culture of white men that’s “devastating” for minorities and women.

But not too devastating, apparently. In January 2019 Politico published a lead story, “How Women Took Over the Military-Industrial Complex.” Out of the top five weapons contractors, four (sans Raytheon) were now led by female CEOs. The piece celebrated the “watershed for what has always been a male-dominated bastion.” Encouraged by the higher percentage of women getting involved in selling munitions, the article was happy to relay that “women are shrewd negotiators.” A victory for feminism, but a defeat for the taxpayer’s wallet.

“There probably has been a decision to pursue outwardly progressive, so-called socially responsible policies that allow them to fit in with the rest of corporate America,” Eli Clifton says. “People will count them in with the group that does those things. And that’s kind of shocking and appalling. This company makes weapons that kill people. And their diversity, and their buy-in to top-line social issues shouldn’t be allowed to whitewash the reality of what they’re doing.”

But for most left-of-center voters and nonprofits, the masquerade is enough.

“This is what they do,” an exasperated Glenn Greenwald, award-winning journalist, explained in November 2020. “They exploit woke ideology and culture war issues to make the left and liberals think that they’re their allies and march behind them. And they put black faces, and gay faces, and female faces onto corporatist and militaristic policies to soften them.”

The military-industrial complex and “woke” identity politics are a complementary match. It’s a divide and conquer strategy that’s already succeeded on the campuses. Eighty-five years ago college students were chanting, “No more battleships, we want schools,” while organizing against the next war. Today a college student is more likely to praise Northrop Grumman for promoting a diverse, intersectional workspace while degrading a white southern military sign-up for upholding “white supremacy.”

Reflecting on the past century, where do things stand?

In the 1930s, a supermajority of Americans supported the curtailment or outright abolition of a rapacious but negligible munitions industry. After World War II, when the threat of a military-industrial complex manifested itself as infinitely more powerful than its anticipatory critics expected, opposition has proved sporadic and temporary.

Perhaps, like a fish who can’t conceive of a world beyond the water, society has become too accustomed to the system. In 1971, scholar Marc Pilusuk and activist Tom Hayden wrote, “Our concept is not that American society contains a ruling military-industrial complex. Our concept is more nearly that American society is a military-industrial complex.”

On the other hand, that view could be too pessimistic. The American people have not rejected accountability for war profiteers. In the modern era, they haven’t been asked. Could they be waiting to excoriate them, if only given an opportunity?

Meet Joe Kent, who’d like to hand them a bullhorn.

A Republican candidate in Washington state’s Third District, Kent is primarying incumbent five-term congresswoman Jaime Herrera Beutler. Already endorsed by former President Donald Trump and some conservative members of Congress, he’s recognized as a competitive challenger. But what makes him a standout in the 2022 midterms is his rooted and robust hostility to the military-industrial complex.

“We have had a military-industrial complex or ruling political or ruling military class for the last twenty years now that has been lying to the American people, and they’ve gotten caught red-handed doing it,” Kent told The American Conservative. “It’s the way our financial system is rigged. It’s this permanent ruling class just really taking advantage of the American people.”

Already enlisted in the U.S. Army before the September 11 attacks, Kent began the Global War on Terror as a “true believer” in the Bush administration’s regime change plans for the region, particularly Iraq. But while there he witnessed firsthand the disconnect between ground level troops and policymakers. “They have an agenda. And that agenda is always being driven towards more war, more occupation, more foreign aid,” he said. “If you dissent from that you’re kind of a heretic.”

Deployed into combat eleven times as a chief warrant officer and then Green Beret with the U.S. Special Forces, Kent gradually came to see the strong financial incentive that he believes disproprotionately drives our nation’s wars and the people who spend their careers advocating them. The particular book which had “a big impact” on him was Colonel David Hackworth’s About Face, which he read in 2005 while fighting in Iraq. Kent has also read General Smedley Butler’s War Is a Racket which he found “very telling.”

But the kick in the teeth came on January 16, 2019, when Joe’s wife and the mother of his sons, U.S. Navy Chief Cryptologic Technician Shannon Kent, was killed in Syria. The Islamic State’s attack on Manbij occurred just over a month after President Trump had announced American troops would be making a full withdrawal.

“The second Trump and…his national security team started talking about getting us out of some of these wars, I saw mid-senior level leaders turn on a commander in chief in a way I’d never seen before,” Kent explained. “And to me that culminated, for me personally, with Trump trying to get our troops out, the military delaying that, slow rolling, Mattis resigning, McGurk resigning, and then my wife being killed in a place that she had no business being after the commander in chief, on a mandate of the American people, ordered them to be out of there.”

When asked if he’d be willing to chair a committee to investigate the military-industrial complex’s actions during the Global War on Terror, similar to the Nye Committee, Kent did not hesitate. “Yes, 100 percent, I would love to,” he said.

“If we have Americans who are actively engaged in war, I don’t think they should be able to profit off of that,” Kent elaborated. “Them profiteering while we have our people in harm’s way I think is a bad precedent to have because that truly turns it into a racket.”

Describing Gerald Nye, Hiram Johnson, William Borah, and others, Professor Jeff Taylor said, “In the end these are men of principle, they’re not men primarily of power or profit.” That is what the nation needs to shake it out of its inoculated stupor. Leaders of principle with the will to address the hard questions, and call these arms manufacturers what they really are: merchants of death.