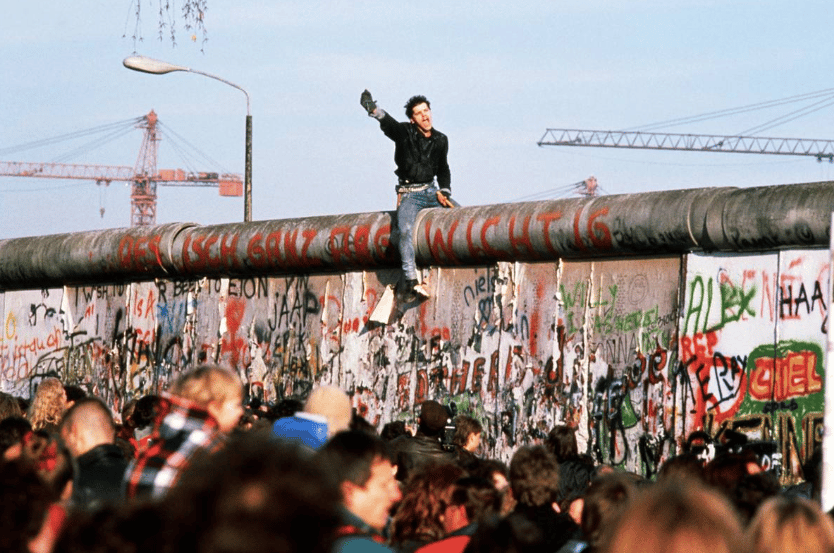

This is the 30th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall — one of the most glorious moments in the modern history of freedom. I first passed through that wall while hitchhiking around Europe in the summer of 1977.

After camping in West German woods within mortar range of the Iron Curtain, I headed out at sunrise to catch a ride into East Germany. A quick hitch with an affable French businessman put me on the Autobahn and into West Berlin before noon. Rambling around the city, I met a young Dutch lesbian who was also surveying the scene. Hendrika slightly resembled a wheel of Gouda cheese but she had bright cheeks and mischievous eyes. She and I were both planning to visit East Berlin, and we figured there would be safety in numbers in enemy territory.

We caught up the next morning and passed through Checkpoint Charlie into the Soviet Bloc’s premier “showplace of communism.” Traveling from West Berlin to East Berlin was like passing into the mirror image of Disneyland. Instead of ticket takers at the entrance of rides, there were undercover cops enticing visitors to exchange currency on the black market — after which they would be fined or jailed. The police were backstopped by civilian informers lurking everywhere, waiting to get paid for tidbits or smears. Hendrika’s fluent German helped keep us from being arrested as we traversed semi-forbidden parts of the city.

On AlexanderPlatz, near the city center, we saw elite East German soldiers goosestepping down the street. West Germany banned the goosestep after the Third Reich was destroyed. But that particular march naturally appealed to the Stalinist regime that the Russians imposed on East Germans after World War II. The goosestep perfectly captures the relation of the State to the people: anyone who did not submit would be crushed. As George Orwell wrote, “The goose-step is one of the most horrible sights in the world, far more terrifying than a dive-bomber. It is simply an affirmation of naked power.”

Walking through East Berlin, I saw many bullet holes in apartment buildings and other structures. I didn’t know whether the damage remained from street battles between fascists and communists in the late 1920s and early 1930s, or from the Red Army’s bloody conquest of the city in 1945, or from the Soviet’s brutal repression of a popular uprising in 1953. Perhaps the bullet holes were left to remind people of the futility of resistance. On the other hand, almost everything looked gray and shabby, so it may have been simply on a long list of blemishes that never got fixed.

Almost all the people I saw on East Berlin streets looked utterly browbeaten. I noted in my journal: “Perhaps despotism drains the soul. It would be difficult to have a high opinion of one’s powers if one was constantly being coerced and subjected to others’ wills.” The East German regime insisted that the Berlin Wall was to keep fascists out from their workers’ paradise. I wasn’t aware of the East German government taking any polls to determine how many of their subjects swallowed that hokum. Regardless, that regime felt entitled to inflict endless delusions on people in order to secure the victory of the proletariat or whatever.

Hendrika and I visited the ghoul-like, cavernous main library in East Berlin. It was necessary to purchase a pass to enter, and only East Berlin students and visitors from non-communist nations were permitted inside. Every room had a guard, and we had to sign a registry and show our passes before entering it. There were vast empty spaces inside, perhaps symbolizing the vast Yukon Territory of knowledge beyond the pale. The local folks using that library didn’t seem to be emitting any mental sparks — maybe intellectual curiosity was considered a thought crime, too? The East Germans toiling with books and papers probably knew that anyone who raced across No Man’s Land to some forbidden idea might be terminated with extreme prejudice. Why have libraries where thinking was a crime? Any government terrified of ideas must be doing something wrong.

As we gallivanted around East Berlin, Hendrika rattled on about life on her commune in southern Holland. She talked of being a “free spirit,” and I soon realized that the Dutch translation meant “also does animals.” She bragged of frolicking with any and all types of mammals with no reservations or prejudices. She was the first person I met who viewed anthrax as a sexually-transmitted disease. (And no, I didn’t.)

Exiting Berlin, I caught a ride to Frankfurt with a friendly young leftist German university student. He said that there was not much difference between “freedom” in West and East Berlin because some workers in West Berlin lived in an area on the edge of city with no subway station and only one supermarket. He lamented that it took them half an hour via a bus line to get to the center of the city. Hence, they had no freedom — just like the people in East Berlin. He stressed that East Germany had many advantages over West Germany, such as free health care and zero unemployment. Maybe he wasn’t aware that the D.D.R. government dictated the occupation each young person must follow? Did this guy not notice the food in the East German markets was utterly grim — almost zero fresh fruits aside from apples? I was puzzled why someone who seemed quite intelligent was utterly oblivious to the catastrophic consequences of destroying economic freedom.

I did not catch the guy’s name and have no idea what happened to him. Maybe I should check to see if there are any German academics on Bernie Sander’s economic policy team. Maybe this guy helped inspire Bernie’s denunciation of “23 underarm spray deodorants” in capitalist stores?

A decade later, I crossed the Berlin Wall plenty of times while getting dirt for articles I wrote for New York Times, Reader’s Digest, Wall Street Journal , and other publications . I caught hell a number of times at East Bloc border crossings but never had a problem in Berlin.

Reprinted from the Mises Institute.