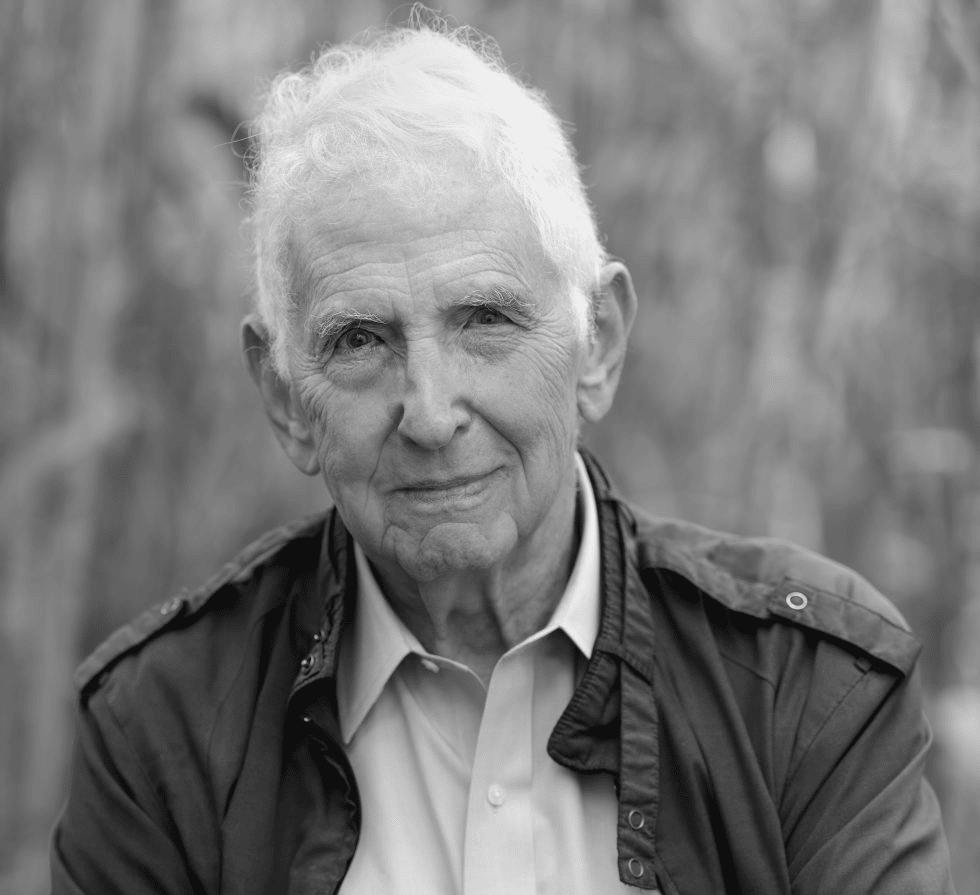

This written statement was made by Daniel Ellsberg, acting as an expert witness for the defense, on September 18, 2020 in front of the British magistrate during the extradition trial of Julian Assange. This transcript is republished from RCReader.com.

1. I provide this statement in the ongoing proceedings USA v Julian Assange. I am aware of the allegations against Mr. Assange and have read the indictments. I am familiar with the nature of the content of the publications in question. I have met Mr. Assange on a number of occasions during the past ten years and have had lengthy discussions with him on issues relevant to the charges he faces.

2. I have been asked by Mr. Assange’s UK lawyers to provide such evidence as I am able. (i) On the basis of my knowledge of Mr. Assange and his work to comment upon what I understand to be the assertion by the prosecution in his case that he does not have “political opinions” or rather, any of relevance to the request for his extradition. I am asked whether I consider opinions of relevance in the context of the indictment he faces can be categorised as recognisable political opinions and such as have been exercised by him in thought, speech and actions to have been intended to alter (and in fact to have altered) the actions of relevant government institutions in particular those of the USA. (ii) On the basis of my knowledge and experience, of the restrictions upon the exposure of classified information even where the intention is to expose grave illegalities carried out within particular wars; and the impact of further restrictions if prosecuted under the Espionage Act.

3. My personal details are these: I was born in Chicago, Illinois in 1931. I was educated at Harvard University, where I received a B.A., summa cum laude, in 1952 and a Ph.D. in Economics in 1962. In 1953-53 I was awarded a Woodrow Wilson Fellowship for study at King’s College, Cambridge University, and in 1957-59 I was a member of the Society of Fellows, Harvard University. From 1954-57 I was an infantry officer in the U.S. Marine Corps.

4. I am a co-founder and current board member of the Freedom of the Press Foundation; Distinguished Research Fellow of the Political Economy Research Institute (PERI), UMass, Amherst; Distinguished Senior Fellow of the Nuclear Age Peace Foundation (NAPF).

5. I am a receipient of numerous awards, many citing my revelation of the Pentagon Papers, including the Right Livelihood Award, 2006; Dresden Peace Prize, 2016; and the Olaf Palme Prize, 2018, in addition to: ACLU Civil Liberties Award, 1971; Americans for Democratic Action Fredom of Speech Award, 1972; Eleanor Roosevelt Peace Award (SANE) 1973 (with Andrei

Sakharov); Gandhi Peace Award, 1978; Society of Profesional Journalists Freedom of Information Award, 2004; German Federation of Scientists Whistleblowerpreis Award, 2004. Nuclear Age Peace Foundation Distinguished Peace Leader Award, 2005; Ron Ridenhour Courage Prize, 2010; Hugh Hefner First Amendment Award, 2013; Bertha Foundation Ben Bagdikian Award, 2013; Media Law Resource Center (MLRC) William J. Brennan Jr. Defense of Freedom Award, 2016.

Relevant Background

6. I set out below my background and experience of relevance to the matters on which I am commenting in this statement.

7. In 1964-65 I was Special Assistant to the Assistant Secretary of Defense for International Security Affairs, with the “super-grade” GS-18: highest level in the Civil Service, the civilian equivalent to major general. In 1965-67, having volunteered for service in Vietnam, I served in the Embassy in Saigon with the grade of FSR-1, as Senior Liaison Officer, and as Special Assistant to the Deputy Ambassador with the duty of evaluating pacification.

8. In 1967-69, I was a member – as a consultant to OSD from the Rand Corporation, to which I had returned – of a McNamara Task Force which produced a 47-volume Top Secret study entitled “History of U.S. Decision-making in Vietnam 1945-68,” later known as the Pentagon Papers. In this role, I had access to documents classified at the ‘secret’ and ‘top secret’ leve. In late 1968 and early 1969 I was a consultant to the Special Assistant to the President for National Security Affairs, Henry Kissinger, on Vietnam options and initial governmental studies on Vietnam.

9. In 1969, together with my colleague Anthony Russo, I made several copies of the Pentagon Papers. I believed that these 7,000 pages of top secret documents demonstrated that the conduct of the war in Vietnam had, over more than one administration, been started and continued by the US Government in the knowledge that it could not be won, and that President Johnson and his administration had lied to Congress and to the public in relation to its origins, costs and prospects.

10. Eventually, in 1971, having provided the documents I had copied to The New York Times and The Washington Post, those newspapers published excerpts of the Pentagon Papers. As a result of the Nixon administration to restrict prior

publication, the US Supreme Court ruled in New York Times v United States that The New York Times had the right to publish the materials which were protected by the First Amendment.

11. I was prosecuted in 1971 for my giving truthful information to the public. The Nixon administration utilised the Espionage Act (intended for spies) against me and my co-accused, we having informed the public of that truthful information.

12. Initially, three charges were brought against me with a possible sentence of 35 years; by the end of the same year I was indicted on 12 counts with a possible sentence of 115 years. Despite the importance and necessity of the action I took I was not permitted to rely upon any justification in my defence to the Espionage Act charges. My trial instead, ended eventually as a result of the revelation of the U.S. government’s criminal actions towards me which led in turn to the convictions of several administration officials.

My Actions

13. It took me months to copy the papers from my safe at the Rand Corporation, one page at a time. I collated the documents as they came off the Xerox machine, and cut off the “top secret” classifications from the top and the bottom of all the pages. I knew then that my actions could result in my going to prison, but I believed that the public had to know about this.

14. I considered my actions then, and now, to be essential and the actions of a patriot.

15. There is strong basis for the widely-held belief that my own action had a tangible effect, as I intended and hoped, on the ability of the American public, Congress and courts, to end both the deaths and the deceptions associated with U.S. involvement in the Vietnam war.

The Impediments to Alternative Means of Disclosure

16. Without publication in the press, it would have proved impossible for the content of the Pentagon Papers to be placed in the public domain. I spent over a year and a half attempting to get hearings in Congress without success.

17. Making the public aware of the Pentagon Papers took years. I tried a number of routes. It was the specific example of Randall Kehler, whom I met in August 1969 as he prepared to go to prison for two years for refusing to cooperate with his draft board, that put in my head the question: “What can I do—non-violently and truthfully—to help end this war, if I am willing to go to jail for it?” And that question found its answer within weeks, at which point I began to copy the documentary evidence in my safe of governmental deception and law-breaking. I decided to demonstrate the truth about the war to Congress and the public, though I expected to spend the rest of my life in prison for doing it.

18. Prior to my releasing the Pentagon Papers, I had possession in my safe in the Pentagon, documents which gave lie to claims of an “unequivocal, unprovocated” attack on U.S. destroyers in the Tonkin Gulf. False claims about the incidents in the Gulf of Tonkin led to the passage of the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution by Congress, which gave President Johnson legal justification for engaging in war against North Vietnam. I was later told by Senator Morse (one of the two senators who had voted against the resolution), that if I had given him that evidence at the time, instead of waiting to 1969 when I provided it to the Senate foreign relations committee, the resolution would have been voted down.

19. I have long regretted not releasing the documents in August 1964, or in the next few months, and it is a heavy burden for me to bear. Had I or one of the scores of other officials who had the same high-level information acted then on our oath of office—which was not an oath to obey the president, nor to keep the secret that he was violating his own sworn obligations, but solely an oath “to support and defend the constitution of the United States”—that terrible war might well have been averted altogether. But to hope to have that effect, we would have needed to disclose the documents when they were

current, before the escalation—not five or seven, or even two, years after the fateful commitments had been made.

20. The routes to exposure in courts of law were entirely blocked. I had been asked to be an expert witness in the trial of a number of highly principled college students and seminarians who had destroyed draft files as a way of protesting peacefully against a continuing believed illegal war. I was not permitted however to present copies of the Pentagon Papers as documentary evidence to support my testimony that the government had been manipulating the democratic process—and concealing its own law-breaking—by lying to the public, a situation that called for dramatic challenge of the sort the defendants

had done. But the Pentagon Papers did not get into the public record on that occasion. The federal judge in that case refused to allow me to offer evidence (the Pentagon Papers, in a briefcase by my side on the witness stand) to support my assertion of that several presidents had lied. When he heard me use the word “lie” he warned the defense lawyer questioning me that both the lawyer and myself would be held in contempt if I used that word again. He had earlier warned the defense attorney that he would not entertain expert testimony “critical of the federal government.”

21. It was precisely this sort of consciousness that seemed to me to need changing if our democratic system were to end the Vietnam tragedy, and I saw nothing other than the Pentagon Papers that might do the job. But that meant that I had to be willing to take measures that would sharply increase the risk of spending the rest of my life in jail.

22. In fact, the disclosures that ended my trial on May 11, 1973—daily revelations for two weeks of a whole series of criminal actions that the Nixon Administration had taken against me to stop further truth-telling about government policy by me

or others—further strengthened Congressional determination to cut off spending on American weapons and bombs that were still killing Vietnamese, even though U.S. casualties had ceased. (The first House majority vote to suspend funding on the war, for bombing of Cambodia, came on May 10, the day before my trial was finally dismissed).

23. It is in the context of the above experience that I can comment upon the position facing Julian Assange, having studied carefully the subject matter of the WikiLeaks publications in 2010 and 2011 concerning the conduct of the Afghan and Iraq wars and detentions in Guantanamo Bay and US diplomatic cables commenting upon aspects of U.S. actions. I have observed the extraordinary breadth and depth of those revelations: revealing as they do the reality of the consequences of war. The exposure of such would be imperative to bring about any alteration of US government policy. I have followed closely the impact of a number of those publications and consider them to be amongst the most important truthful revelations of hidden criminal state behaviour that have been made public in U.S. history. My own actions in relation to the Pentagon Papers and the consequences of their publication have been acknowledged to have performed such a radical change of understanding. I view the WikiLeaks publications of 2010 and 2011 to be of comparable importance

Re: Mr Assange’s Political Opinions

24. I comment that I find extraordinary the assertion that Mr. Assange does not possess political opinions of direct relevance to his intended prosecution in the USA and the ongoing attempt to extradite him for charges under the Espionage Act and the Computer Fraud and Abuse Acts. The opinions that it is very obvious that he has, (amongst many of sophistication and complexity on a range of issues), in particular in the light of the prosecution he faces, are very clearly focussed fairly and squarely at the centre of political movements of which I regard myself as part and which much of my life has spent committed to pursuing. (i) The movement to bring transparency to government actions which required to be exposed for the public to understand them and to achieve alteration, in particular those that touch upon the gravest of issues, (very frequently where the claim for “national security” has been erected to obscure illegality and deceit often on a major scale). (ii) In respect of the “anti-war”/”peace” movement I have heard and read many of Mr. Assange’s public statements on these issues. They have constituted an important part of public debate and knowledge on the subject of war and in particular the subject of the Afghan and Iraq wars, the publications for which he is being prosecuted having constitued an enormous body of incontrovertible data that has allowed for a universal body of knowledge and consequent understanding and action. I have also spoken to him privately over many hours on the same subjects. Indeed I spoke to him during the course of 2010/2011 at a time when some of the published material had not yet seen the light of day. I was able to observe his approach was the exact opposite of reckless publication and nor would he wilfully expose others to harm. WikiLeaks could have published the entirety of the material on receipt. Instead I was able to observe but also to discuss with him the unprecedented steps he initiated, of engaging with convential media partners, for the purpose of ensuring that the impact of publication was not only widespread, but that

it might be the most likely route to have effect upon U.S. government policy and its alteration.

25. I hope that my comments might assist the Court in its understanding of what it is that Mr. Assange faces and its context. I observe the closest of similarities to the position I faced, where the exposure of illegality and criminal acts institutionally and by individuals was intended to be crushed by the administration carrying out those illegalities; in part in revenge for my act of exposing them but in part to crush all such future exposure of the truth and when there was no other way. I have closely observed the actions of the US government, its military and its intelligence agency the CIA and that the actions in question were never intended to be revealed (including rendition and torture, the use of “black sites” and crimes against humanity). I have also observed that those who have been party to exposing them have been and continue to be themselves threatened and criminalised. The actions brought against me involved a political determination (later exposed) that the Department of Justice be used to bring those actions even where the justification for their publication had been acknowledged. By the eventual time of my trial in 1973 US policies had indeed already been put into reverse as a result of the newspapers’ publications years before.

WikiLeaks’ Publication of the Afghan War Logs

26. When stories based on the Afghan war logs began to be published, I felt that the comparison between those publications and the Pentagon Papers was inevitable in one major respect: in terms of volume, there had been nothing like it since the Pentagon Papers. It was the first unauthorised disclosure of such magnitude in nearly 40 years. Moreover, it had the advantage of being more current; the most recent of the Pentagon Papers were dated three years before their release but some of the documents in the Afghan war diaries were dated six months earlier than their release.

27. There were also some differences which I noted. The Pentagon Papers were high-level, top-secret documents on internal estimates, alternatives being debated, presidential directives, and so forth. The Afghanistan documents are lower-level field reports, of the kind that I was reading and writing when I was a foreign-service officer in Vietnam. In fact, I could have written a number of them—they were very like the ones I wrote, with the place names changed. Which confirmed my view held for a number of years that I saw the war in Afghanistan as ‘Vietnamistan’ in that it was a replay of the stalemate the USA had been in 40 years ago. My further observation is that the civilian victims of the population ceased to be seen as human beings whose lives had the same worth as those involved in the bringing of war to their respective countries; in those circumstances, crimes against humanity of the worst kind, and mass atrocities could and did become the norm.

28. My attention, as with the rest of the world was first caught by the video of the Apache helicopter assault in Iraq, which became known as ‘Collateral Murder.’ That title, given by Assange, was often criticised as overly accusatory. On the contrary, as a former battalion training officer (Third Battalion, Second Marines) and rifle company commander, I was acutely aware that what was depicted in that video deserved the term murder, a war crime. (In fact, deliberate as the killing of civilians was, it was the word “collateral” that was questionable.) The American public needed urgently to know what was being done routinely in their name, and there was no other way for them to learn it than by unauthorized disclosure.

29. I came to appreciate, in relation to the publication of subsequent material, the ways in which Assange had developed and was continuing to develop technology which enabled whistleblowers to bring evidence of such criminality into the public domain. I understood at the time that Assange planned to offer this same technology to newspapers at the time and I note that since 2010, most major media outlets, and even the CIA, have developed secure technology to allow whistleblowers to share information in a secure and anonymous way. Indeed, the Freedom of the Press Foundation—of which I was a co-founder and am a current board member—has developed and widely made available to media just such a software system, “Secure Drop.”

My Prosecution Under the Espionage Act

30. It is widely acknowledged that the copying done by me and the much later, the publication of the Pentagon Papers, can reasonably be held to have contributed first, to the ending of U.S. casualties in Vietnam, and subsequently to the ending of the war and to the destruction of Vietnam and the deaths of its people. However those effects depended in large part on the Nixon adminstrations over-reaction to my actions, its actions having been taken in fear of the political consequences of better public information on a policy that was still being conducted largely in secret to hide its reckless illegality.

31. As has become very well known, after the publication of the papers, President Nixon was so disturbed by the media’s portrayal of my actions that he ordered his aides to look for damaging personal information to destroy my reputation. “Don’t worry about his trial” the President told then Attorney General John Mitchell, “Just get everything out…we want to destroy him in the press” and a clandestine White House unit led by Gordon Liddy and Howard Hunt broke into the offices of my psychiatrist in September 1971, discovered only after a further attempted burglary took place (the Watergate burglary). Further still, President Nixon and his associates had brought in a dozen CIA assets, under the direction of Howard Hunt and Gordon Liddy, from Miami on May 3rd 1972, with orders to incapacitate me totally. Bernard Baker, a CIA asset, later told me that his mission was to break both of my legs and I later learnt (from the special prosecutor in their case) that there was a plan for these CIA assets to attack me in the course of a rally that I was speaking to on the steps of the Capitol on May 3 1972. Three days before my trial came to an end, evidence of unlawful wire tapping surveillance surfaced. The trial judge, William Byrne on May 11th 1973 stated “The totality of the circumstances of this case…offend a sense of justice. The bizarre events have incurably infected the prosecution of this case.” He dismissed all charges with prejudice (so that I could not face these charges again.)

32. I do not canvas in this statement the fact that a collateral challenge was intended to be argued at my trial. However, so far as the Espionage Act itself and any challenge based on the necessary action that I would wish to have made, the response of my trial judge is very well known. When I attempted to answer my lawyer’s question as to “why” I had copied the Pentagon Papers—in part, to explain my judgment that the documents were improperly classified to keep them not from an enemy but from the American public and to argue the necessity therefore of their being made public because of their content—the court ruled the question as “irrelevant” and I was silenced before I could begin. My lawyer said that he “Had never heard of a case where a defendant was not permitted to tell the jury why he did what he did”. Judge Byrne responded “Well you’re hearing one now.” (Of grave concern was the revelation I later learned that the President, intent on preventing the revelation of criminal acts against me surfacing during the trial, had offered the trial judge, Matthew Byrne, the thenopen post of Director of the FBI (a childhood ambition of Byrne’s), on the understanding that he would end the trial expeditiously (presumably, with conviction).

33. Without the revelation of these supervening illegal events above, if facing the same circumstances today, and charged under the Espionage Act, I am certain that I would be convicted. I observe that this has been the pattern since in prosecutions under the Espionage Act of whistleblowers seeking to raise the public interest attaching to the publications in question. I noted that the military judge at the trial of Chelsea Manning did not allow Manning or her lawyer to argue her intent, the lack of damage to the U.S., over classification of the cables or the benefits of the leaks until she was already found guilty.