A principal goal of Stark Realities is to “expose fundamental myths across the political spectrum”—and few myths are as universally embraced as the notion that US participation in World War II (1941-1945) lifted the American economy out of the Great Depression.

This myth is dangerous not only because it leads citizens and politicians to see a bright side of war that doesn’t really exist, but also because it helps foster a belief that government spending is essential to countering economic downturns. That belief, in turn, has helped propel us to a point where the national debt now exceeds $34.6 trillion, with interest payments alone on pace to reach $1 trillion a year in 2026, inviting financial catastrophe.

In part, the wartime-prosperity myth springs from the fact that, during conflict on the scale of World War II, broad, macroeconomic measures like gross national product (GNP) and the unemployment rate are completely untethered from the economy’s most important facet: the standard of living enjoyed—or endured—by everyday people.

Between 1940 and 1944, real GNP rose at an unprecedented 13% annual clip. Using GNP alone, one would think the war delivered a major improvement in the standard of living, with Americans enjoying a greater abundance of goods, accompanied by a rise in quality, selection and affordability.

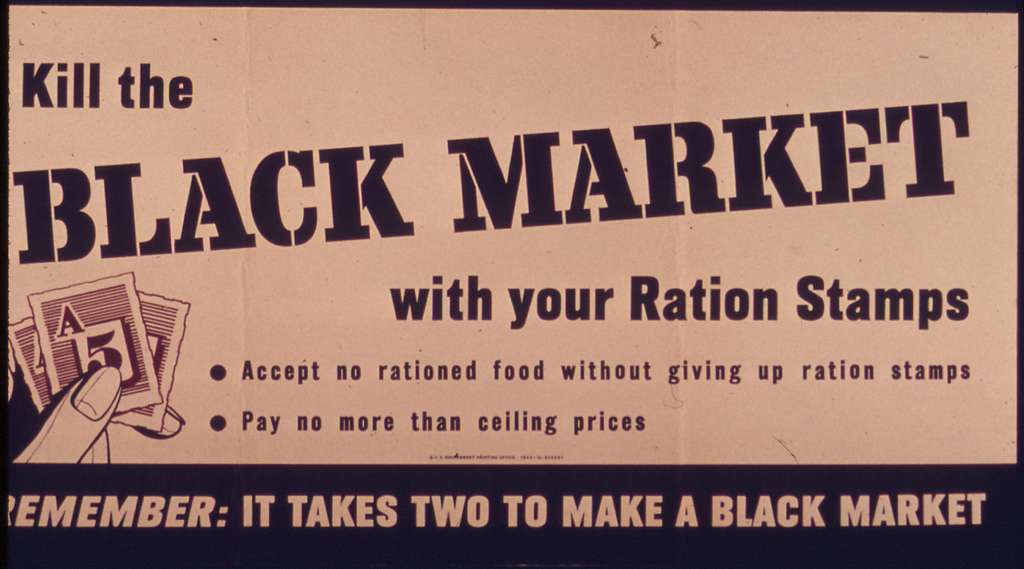

The reality was the exact opposite: Americans endured rationing, shortages, declining product quality, and the outright unavailability of many new goods, such as cars, trucks and stoves. This was the inevitable result of factories and raw materials being redirected from the creation of things consumers want to building things like tanks and fighter planes that do nothing whatsoever to improve people’s lives (setting aside the separate issue of the war’s justness).

In many respects, America experienced an outright economic devolution. In the preceding century, industrialization and the division of labor led to enormous increases in productivity. During World War II, however, shortages motivated people who’d contentedly relied on farmers to start growing their own food and canning it. The scarcity of new clothing led homemakers to redirect time and energy to sewing their own garments and resewing them to stretch as much use out them as possible.

“Those remaining on the home front were forced to produce for themselves what they had previously been able to purchase,” wrote Steven Horwitz and Michael J. McPhillips. “The household again became a center of production rather than consumption alone.”