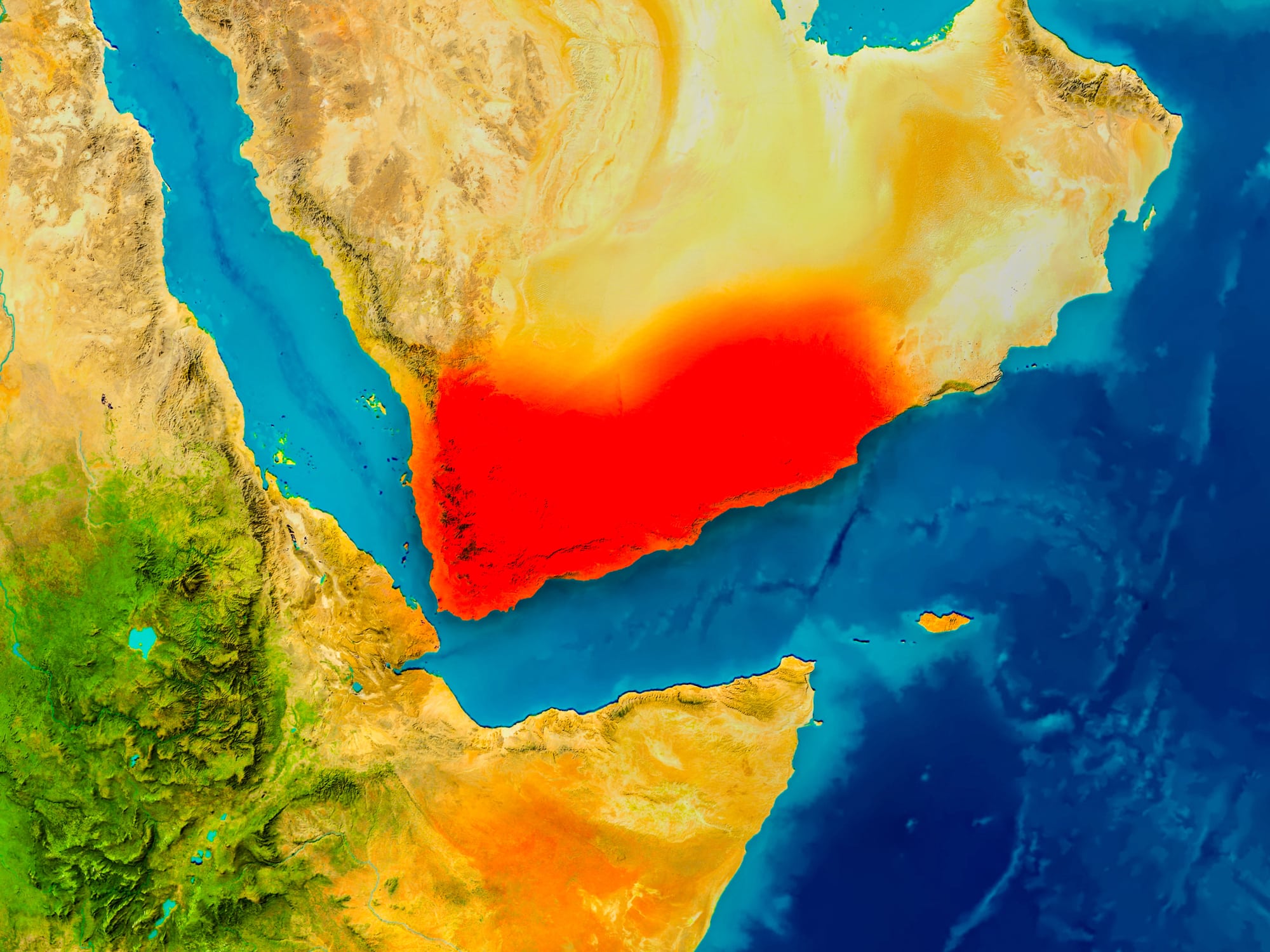

Since the middle of March, the United States has launched extensive air and naval strikes targeting Houthi installations across Yemen. These strikes killed at least 53 people, including Houthi leaders, and injured many others.

The strikes were ostensibly aimed at countering Houthi attacks on global sea lanes. These airstrikes are just the latest in Washington’s escalation against the Houthis, who the Trump administration re-designated as a “Foreign Terrorist Organization” in early 2025 and has repeatedly linked to Iran.

The corporate media would have people believe that the Houthis are a mindless proxy force of Iran that causes chaos for the sake of causing chaos. Not only is the perception of the Houthis cartoonish, but it is also dangerously misleading as it lends credence to the Iran hawk’s agenda of using military action to topple the Iranian regime.

U.S. national security officials have not looked at the root causes of the conflict in Yemen, which is essential if we want to comprehend the nuances of this conflict.

Historically, modern-day Yemen has been a politically fragmented country. Yemen was unified in 1990, merging the north (Yemen Arab Republic) and the Soviet-aligned south (People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen). Ali Abdullah Saleh, who had ruled North Yemen since 1978, became president of the newly unified Yemen.

His stewardship of the country was marred by corruption, authoritarianism, and tribal patronage networks that alienated many Yemenis. Intermittent upheavals and even a brief civil war in 1994 rocked the country throughout the 1990s.

Despite nominal unity, southern Yemenis remained disenfranchised. Grievances over lost jobs, land, and influence in the post-1994 order fueled a growing southern separatist sentiment in later years. Southern Yemenis were not alone in their displeasure toward the Saleh government though.

The Houthi movement (Ansar Allah) emerged in the early 2000s in Yemen’s northern Saada province, rooted in Zaydi Shia revivalism and opposition to Saleh’s government. It was initially a political-religious movement led by Hussein Badreddin al-Houthi, advocating for the rights of Zaydis and criticizing the government’s corruption and alliance with the United States and Saudi Arabia.

Curiously, the Houthis had the tacit support from President Saleh, who saw them as a useful counterweight to Sunni Islamist factions and Saudi influence to the country’s north.

This tacit alliance frayed after 2000 when Saleh ended a border dispute with Saudi Arabia and moved to assert control over the Saada governorate—a Houthi stronghold. Feeling betrayed, the Houthis started to resist the Saleh government’s efforts to disarm them.

Open insurgency kicked off in 2004, marking the first of six intermittent Saada Wars between the Houthis and Saleh’s forces. In June 2004, government troops moved to arrest Hussein al-Houthi; heavy fighting ensued until Hussein was killed in September 2004, thereby cementing his martyr status.

Hussein’s brother Abdul-Malik al-Houth assumed leadership of the resistance movement and continued the struggle against the Saleh government. Several bouts of conflict flared up from 2005 to 2009 that did not end conclusively. The conflict took a new dimension in 2009 when Saudi Arabia launched “Operation Scorched Earth” alongside Yemeni forces to quell the Houthi revolt.

This intervention made the war spill over into Saudi border areas and hardened the Houthis’ resolve against the Saudis. A ceasefire was finally reached in February 2010, temporarily halting the rebellion for the time being. Multiple years of fighting gave the Houthis valuable military experience while also solidifying their control of northern Yemen.

The Arab Spring of 2011 gave the Houthis an opportune moment to expand their political power as protests broke out against Saleh’s government. Under pressure from the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), Saleh stepped down in 2012 in exchange for immunity, handing power to his vice president, Abdrabbuh Mansur Hadi.

Hadi’s transitional government was weak and failed to address Yemen’s longstanding economic woes and political fragmentation. The transitional government proposed a federal state of six regions. The Houthis rejected such a proposal, feeling a six-region federation would dilute their power.

Recognizing there was no political solution to address their grievances, the Houthis took arms in 2014 and seized control of the capital Sana’a. By early 2015, they placed Hadi under house arrest, effectively overthrowing the internationally recognized government.

As the Houthis advanced southward and seized additional territory, President Hadi fled to Aden, and subsequently sought refuge in Saudi Arabia.

Strategists in Washington and Riyadh were convinced the militants’ surprising military gains were the product of an alliance they forged with Iran. Out of fear that Iran was establishing a presence on its southern border, Saudi Arabia launched a military intervention—codenamed Operation Decisive Storm—in March 2015.

The Iranian influence over the Houthis is overstated. The Houthis are not direct proxies of Iran, but they have found a willing patron in Tehran. Iranian support to the Houthis reportedly began as early as 2009, during the Houthis’ insurgency against the Saleh government, though there are nuances with this relationship.

The Zaydis are “Fiver” Shiites, distinct from Iran’s Twelver Shiism. The relationship is one of a willing partnership rather than direct proxy control, with the Houthis pursuing their own agenda that happens to align with Iran’s regional interests of poking their Saudi rivals in the eye wherever they can. Thus far, Tehran has steadily provided material and political support that has enhanced the Houthis’ capabilities.

Nevertheless, such nuances have not registered with foreign policy decisionmakers. Teaming up with Arab states such as Bahrain, Egypt, Jordan, Kuwait, Morocco, Qatar (until mid-2017), Sudan, and the United Arab Emirates, the Saudis sought to restore Hadi’s government, defeat the Houthi rebels, and quell Iranian influence. The United States, under Barack Obama’s watch, not only gave the diplomatic greenlight to the Saudi intervention but also provided intelligence, aerial refueling, and advanced munitions to the coalition forces.

In the middle of 2015, Saudi and Emirati special forces made rapid gains and helped pro-Hadi factions push the Houthis out of Aden and much of South Yemen. The coalition also imposed a de facto naval and air blockade on Houthi-controlled areas with the ostensive aim of preventing Iranian arms smuggling.

The Saudi-led coalition’s heavy bombardment—bolstered by American and British-supplied military aid—has not only inflicted severe damage on Houthi targets but also caused large-scale civilian casualties. By April 2022, the coalition had conducted over 25,000 air raids in Yemen.

As of the end of 2021, the United Nations estimated roughly 377,000 deaths from the war. Frontline combat alone has killed tens of thousands (estimates of combat fatalities range from 100,000 to 150,000 by various monitoring groups). The war has also internally displaced four million Yemenis.

Despite the devastation the Saudis and their allies have brought about, the war eventually hit a slog both militarily and politically. In the south, the UAE—a key coalition member—increasingly backed the Southern Transitional Council (STC), a secessionist body formed in 2017 that worked to re-establish an independent South Yemen. In January 2018, the STC’s UAE-backed paramilitaries turned on the Hadi government and seized control of Aden.

This intra-coalition rift was patched up by a Saudi-brokered Riyadh Agreement in November 2019, which proposed a power-sharing government including the STC. Nevertheless, tensions continued, and the south remained split between pro-STC and pro-Hadi factions. By 2020, the UAE had withdrawn most ground troops, though it continued to wield influence through southern proxies and control of areas like Aden and Socotra Island.

Israel has also inserted itself in the war in Yemen, especially since late 2023, in response to Houthi attacks on Israeli shipping. The Houthis, in solidarity with the Palestinians being ethnically cleansed in Gaza, launched several attacks against Israeli commercial assets in the Red Sea and Israel proper in late 2023 and early 2024. Israel retaliated by executing multiple airstrikes targeting Houthi-controlled infrastructure in Yemen. These strikes have hit Sana’a International Airport, Red Sea ports on Yemen’s western coast, several power stations, and oil facilities.

So far, the conflict in Yemen continues with no real end in sight. Even though Donald Trump campaigned to end the United States’ fixation with forever wars, he is still signing off on military action against the Houthis.

If Trump genuinely intends to fulfill his promise of ending forever wars, he should immediately halt military aid to Saudi Arabia. Allowing this conflict to continue risks dragging the U.S. into yet another Middle Eastern quagmire.