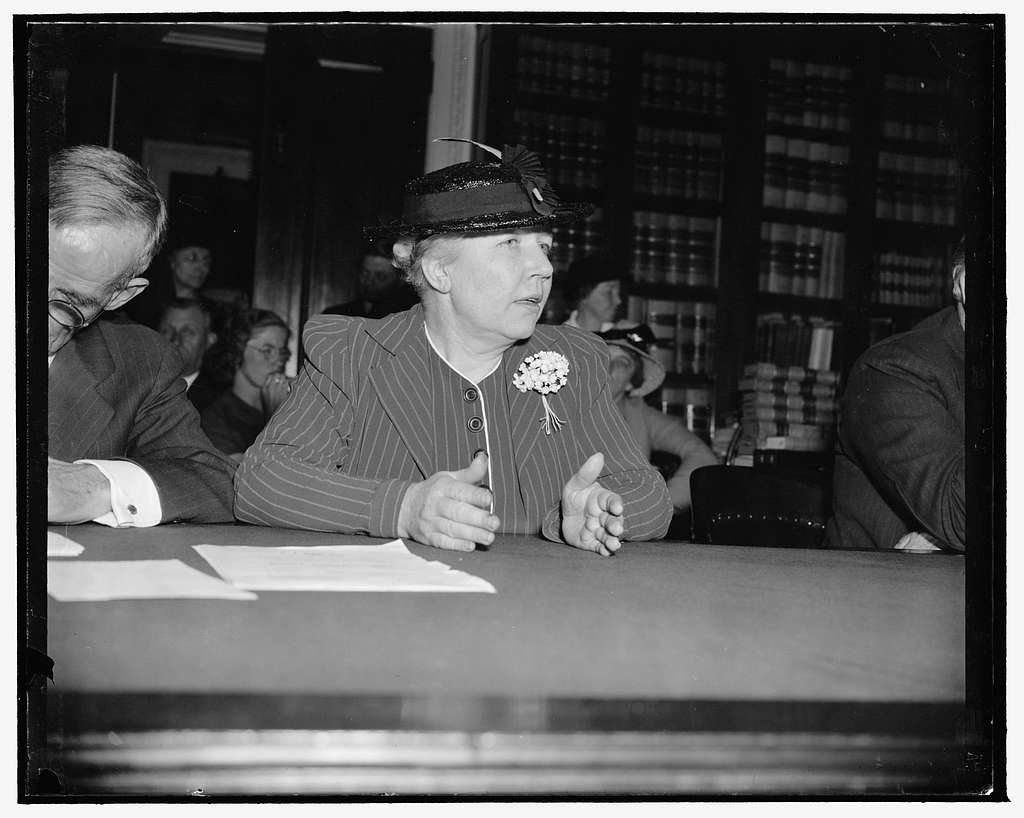

It was on this day in 1886 that the journalist and author Rose Wilder Lane was born in a little house on the prairie that she and her mother, Laura Ingalls Wilder, would later make famous. A brilliant, moody, and independent spirit, Rose was eventually to become one of the most important voices of American liberty, and in 1943, published The Discovery of Freedom, a pathbreaking book that helped spark the revival of interest in free markets and individualism in the later 20th century.

Ironic, then, that she started out as a socialist.

Lane grew up hating the life on the farm, and decided at an early age to become a journalist and traveler. In the 1920s, she went to Europe to report on the Red Cross’s efforts to help refugees in the wake of World War I, but during her travels, she was horrified by what she witnessed in the new Soviet Union. Bolshevik chiefs had begun confiscating food and forcing the people of Armenia and Georgia into manual labor to get it back. “We intend to redistribute it to the neediest,” one Soviet soldier told her. “We will see that they are the most needy by making them work for it.” After witnessing collectivism in action, Rose returned to the United States prepared to rethink everything she thought she had known about economics and politics.

In 1926, she arrived back at her parents’ farm, and dove into works on politics and history. In a letter to the journalist Dorothy Thompson, whom she had met in Paris, Lane described how her studies opened her eyes to the uniqueness of American freedom. America was criticized for “its lack of form,” she wrote. But now she saw that formlessness—in other words, its social and economic fluidity—as a great blessing: “It’s exactly stability which America discards.… Is it possible for a civilization to be wholly dynamic? Wholly a vibration, a becoming, a force existing in itself, without direction, without an object for its verb? A civilization always becoming, never being, never never having the stability, the form, which is the beginning of death?”

What Lane was describing was the dynamism of a free society, in which individuals are free to discover their own paths—both metaphorically and literally. In her book Give Me Liberty, published in 1936, Lane would explain how the freedom to choose enabled people to establish their own rules of social interaction, and accomplish their own purposes, without being dictated to by the state. She used a simple illustration, comparing the way people leave a theater at the end of a show to the way in which a teacher maintains order in a classroom. “No crowd leaves a theater with any efficiency,” she wrote, “yet we usually reach the sidewalk without a fight.” By contrast, any classroom instructor “knows that order cannot be maintained without regulation, supervision, and discipline.” That distinction underlined the difference between two kinds of societies: that in which people are at liberty to pursue their own goals, and that in which an authority figure controls people’s behavior in order to accomplish some single collective goal that they themselves might not share. Years later, the economist F.A. Hayek would label this the difference between “spontaneous” and “constructed” orders. Simply put, people don’t need an authority figure to tell them how to live—or, as Lane liked to put it, the very idea of Authority with a capital “A,” whether it be in the form of socialism, Nazism, or anything else, is fallacious: wealth, social harmony, and other blessings are not created by kings, dictators, or presidents. They are the result of individual initiative. And if that initiative is stifled by government intervention, the results can be wasteful, foolhardy, or even catastrophic.

As I detail in my new book, Freedom’s Furies, this and other discoveries helped make Lane—along with her friend and mentor Isabel Paterson, and another of Paterson’s admirers, Ayn Rand—one of a trio of women who would help revolutionize Americans’ conception of liberty in the age of the Depression and World War II. In 1943, all three of them published books—Lane’s The Discovery of Freedom, Paterson’s The God of the Machine, and Rand’s The Fountainhead—that helped spark the modern liberty movement. The journalist William F. Buckley later called them “the three furies of modern libertarianism.”

I spoke about Lane and her friends at a book forum at the Cato Institute last week, on a panel that included Reason magazine’s Elizabeth Nolan Brown, the Libertarian Party’s Carla Howell, and Cato’s Kat Murti and Paul Meany. You can watch that here:

Along with her own novels, Lane helped incorporate arguments for self‐reliance and freedom into the Little House novels that she co‐wrote with her mother. And she always remained an adventurous and rebellious spirit. Months after The Discovery of Freedom appeared, she wrote an angry postcard to a political commentator in which she criticized Social Security. In response, the FBI dispatched police officers to her home to question her about her “subversion.” To one officer’s questioning, she angrily replied, “I’m as subversive as hell!”—and demanded an apology from J. Edgar Hoover. (The FBI continued to surveil her, however.)

Lane remained a rebel until her death. In 1963, she published The Woman’s Day Book of American Needlework, which combined her lifelong interest in textile arts with her love of America’s culture of liberty. The arts of embroidery, crochet, and quilting, she argued, revealed how American women had found the freedom to express themselves and provide for their families, in ways unprecedented in history. Two years after that, Lane traveled to Vietnam to report on the war for Woman’s Day magazine. In 1968, she died at her home in Danbury, Connecticut, at the age of 81.

Lane was a pioneering feminist figure, and a fascinating personality—as well as being one of the Founding Mothers of our ideas of individual liberty. We would do well to remember her fascinating life story, and appreciate the ideas she helped preserve for us.

This article was originally featured at the Cato Institute and is republished with permission.