“Germ and chemical weapons may often be weak in their battlefield applications but they are always strong in their emotiveness. Accusations of association with them have for centuries, even millennia, been used by well-intentioned as well as unscrupulous people to vilify enemies and to calumniate rivals. Can onlookers protect themselves against the possibility of such assaults upon their common sense today?”- Julian Perry Robinson

On the morning of August 21, 2013, a flurry of videos appeared on social media alleging to show the aftermath of a mass chemical attack in Syria. The Obama administration quickly accused the Syrian government of launching a barrage of sarin filled rockets toward the Damascus suburbs of eastern and western Ghouta, thereby murdering 1,429 civilians, including 456 children.

Nine years later, the perception persists that this terrible crime was carried out by the Syrian government. However, with the passing of time, and as more details have surfaced, it has become clear that the Syrian government did not carry out the Ghouta chemical attack.

This was evident even in 2013 when the attack occurred, given the incentives faced by both sides in the conflict, and given the timing of the attack.

A year before, in August 2012, President Barack Obama had declared that any use of chemical weapons constituted a “red line” that, if crossed, would trigger U.S. military intervention against the Syrian government.

The Salafist militias comprising the opposition, broadly known as the Free Syrian Army (FSA) and the al-Qaeda-affiliated Nusra Front, therefore had every incentive to carry out a false flag chemical attack that could be blamed on Syrian President Bashar al-Assad. To topple the Syrian government, the Salafist insurgents both needed and wanted a western bombing campaign of the sort that had toppled the Libyan government in August 2011.

Syrian opposition leaders began demanding a U.S.-imposed no-fly zone over Syria starting as early as September 2011, shortly before Libyan President Moammar Qaddafi was murdered by Islamist militants fighting under the umbrella of NATO warplanes, and long before Obama announced his red line.

In contrast, it was in President Assad’s interest to prevent any use of chemical weapons by the Syrian army. Failure to do so would almost guarantee his government would be toppled, further plunging Syria into the type of chaos that had enveloped Libya, while leaving Assad to suffer Qaddafi’s gruesome fate.

It is no wonder that, despite accusing Assad of carrying out the Ghouta chemical attacks, neither American or British intelligence could provide a possible rationale at the time as to why Assad would do it, or what advantage he or the Syrian army would gain by it.

Many observers have also noted the timing of the alleged attack. If Assad ordered it, this means he carried out a chemical attack in the Damascus suburbs just three days after UN chemical weapons inspectors had arrived in Syria’s capital, at Assad’s own invitation, to investigate allegations chemical weapons use by the opposition in the town of Khan al-Assal four months previous. It is highly improbable that Assad would have carried out a chemical attack and at the same time ensured that UN inspectors would be immediately present to investigate it.

Even more improbable is that Assad would carry out a chemical attack at a time when he was winning the war, and just as U.S. and NATO forces were preparing for a large-scale military intervention in Syria, the likes of which only a breach of Obama’s red line could trigger.

For example, in June 2013, Obama administration officials concluded that a more direct intervention, including providing weapons to the so-called rebels and possibly imposing a no-fly zone “was needed to stem the tide of Assad victories.” That same month, U.S. planners stationed F-16 warplanes and Patriot missile batteries in neighboring Jordan in preparation to impose a no-fly zone.

In July 2013, amidst calls from Senator John McCain (R-AZ), Senator Carl Levin (D-MI), and others for imposing a no-fly zone, General Martin Dempsey laid out detailed options for military intervention in Syria to the White House. Also in July, the House and Senate Intelligence Committees approved White House and CIA plans to directly arm the Salafist militias comprising the FSA. Previously, U.S. planners had relied on Saudi, Qatari, and Turkish intelligence to do so.

On August 13, fully nine days before the alleged chemical attack in Ghouta, FSA commanders in Turkey had started “advance preparations for a major, irregular military surge.” The commanders had been told by U.S., Turkish, and Qatari intelligence officials that a U.S.-led intervention in Syria was imminent and were ordered to “prepare their forces quickly to exploit the U.S. bombing, march into Damascus, and remove the Bashar al-Assad government.” On August 17, four days before the Ghouta attack, CIA and Israeli operatives embedded with FSA fighters entered Syria from Jordan, reaching as far as Ghouta, in what the French newspaper La Figaro described as the beginning of the “anti-Assad operation.” On August 21, the day the Ghouta chemical attack occurred, U.S., Turkish, and Qatari intelligence distributed weapons “unprecedented in scope” to FSA commanders in preparation for the assault on Damascus.

Though the success of the regime change operation was predicated on a U.S.-led bombing campaign, this could not happen without President Obama’s approval, which he had until that time refused to give. The alleged chemical attack in Ghouta on August 21 therefore came at exactly the right time to illustrate that Obama’s red line had been crossed and allow the intervention to begin.

Because of this, claims of Assad’s guilt were questioned at the time even by dissenting U.S. intelligence analysts, who according to the Associated Press, wondered whether so-called “rebels could have carried out the attack in a callous and calculated attempt to draw the West into the war.”

As The New York Times observed one month before the Ghouta attack, “Assad now seems likely to cling to power for the foreseeable future.” Consequently, Assad did not need to carry out a chemical attack to stay in power. Syrian opposition leaders, on the other hand, desperately needed Assad to be blamed for one to take power themselves.

But now, almost ten years later, as additional information has come to light, it is beyond doubt that what happened in Ghouta on August 21, 2013, was a false flag operation carried out by a Saudi-sponsored Salafist opposition group, Liwa al-Islam.

Additionally, it is now clear that although sarin-filled rockets were fired at multiple neighborhoods in the Ghouta region that day, most of the victims were not killed by sarin. Rather, most victims were likely suffocated to death using either carbon monoxide or cyanide, after which their bodies were collected in make-shift morgues and presented in videos published by opposition media as victims of a government sarin attack.

The identity and exact number of victims remains unclear. However, it is likely that most of the victims were not pro-opposition civilians, as is commonly assumed, but rather government supporters who had been taken captive and then murdered by Liwa al-Islam in a carefully managed massacre. For this reason, it is more accurate to refer to the events in Ghouta as a massacre, rather than as a chemical attack.

Perhaps most importantly, it is now clear that Liwa al-Islam was not acting alone, hoping to deceive the western powers into launching a massive military intervention on its behalf. Although militants from Liwa al-Islam constituted the boots on the ground that carried out the Ghouta massacre, they did so as part of a broader regime change operation, which was planned and initiated by a U.S.-led coalition of foreign intelligence agencies even prior to the outbreak of anti-government protests known as the Arab Spring.

As I have detailed elsewhere, prominent neoconservatives in the Bush administration partnered with Saudi Prince Bandar bin Sultan in the wake of 9/11 to begin efforts to topple the Syrian government. These efforts intensified in 2005, and eventually sparked the anti-government protests that erupted in Syria in March 2011. U.S. planners simultaneously launched an al-Qaeda-led insurgency that used these protests as cover to attack Syrian police, soldiers, and security forces.

U.S. efforts to effect regime change continued in 2012 under the umbrella of operation Timber Sycamore, the CIA program established to further fund and arm the al-Qaeda-led insurgency. Launched by then-CIA chief David Petraeus and subsequently overseen by his successor, John Brennan, the covert program would become the most expensive in the agency’s dark seven-decade history, with much of the funding coming from off-the-books sources, specifically from Prince Bandar and Saudi intelligence.

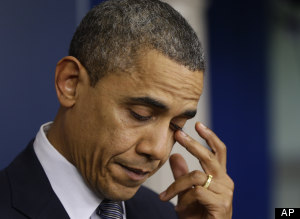

A false flag chemical attack, accompanied by horrific videos of dead women and children, and portraying Bashar al-Assad as a modern-day Hitler, was the CIA’s best hope to pressure a reluctant Barack Obama into green lighting the Libya-style western bombing campaign.

In a manner reminiscent of the Safari Club of the 1980s, the CIA partnered with Saudi, Israeli, British, French, and Turkish intelligence to execute the Ghouta false flag operation, with Bandar and Brennan serving as point persons. For this reason, the 2013 Ghouta massacre should be seen as part of the broader U.S.-led operation to carry out regime change in Syria that began over a decade earlier.

Whose Red Line?

In August 2020, President Obama declared his “red line” regarding chemical weapons in Syria. He stated that, “We cannot have a situation in which chemical or biological weapons are falling into the hands of the wrong people…We have been very clear to the Assad regime but also to other players on the ground that a red line for us is, we start seeing a whole bunch of weapons moving around or being utilized.” Obama stated further that any such use of chemical weapons “would change my calculus…would change my equation” and open the door to U.S. military intervention in the conflict.

According to The New York Times, the red line originated after “American intelligence agencies began picking up communications with ominous signals that Mr. Assad’s military was moving chemical weapons and possibly mixing them in preparation for use. Mr. Obama ordered a series of urgent meetings, and on Aug. 20 [2012] he made a comment that would come to haunt him.”

Obama’s apparent concern was not necessarily that the Syrian government would use chemical weapons to help defeat the U.S.-backed Salafist insurgency it faced, but that the chaos of war could allow Syria’s chemical weapons, which were developed as a deterrent to a conventional military invasion by Israel, to fall out of Syrian government control and into the hands of non-state actors, including either Hezbollah or al-Qaeda.

Under this pretext, CNN reported in December 2012 that according to a senior U.S. official, “The United States and some European allies are using defense contractors to train Syrian rebels on how to secure chemical weapons stockpiles in Syria.”

Surprisingly, the concept of the red line did not originate with Obama himself, but rather with Israeli planners. The Wall Street Journal reported that “the use of the ‘red line’ expression in the context of Syrian chemical weapons started with Israeli officials, who used the phrase in private discussions with their American counterparts. It quickly became part of internal administration discussions. George Little, the Pentagon spokesman, used the phrase publicly in July 2012, and then-Secretary of State Hillary Clinton used it during a visit to Turkey. One top administration official was so worried about the ‘red-line’ talk in the halls of the White House and State Department that he asked aides not to use the phrase.”

Worries about the “red line talk” were likely driven by the realization that this strongly incentivized the opposition to claim that the Syrian army had used chemical weapons as part of the war effort itself. If convincing claims of a Syrian government chemical attack against insurgents or civilians were to be widely disseminated in the western media, this could pressure Obama to establish a Libya style no-fly zone over Syria.

For example, journalist Charles Glass reported that “A former US ambassador to the Middle East told me, ‘The “red line” was an open invitation to a false-flag operation.’”

Clinton also began to promote the idea of a no-fly zone at this time, following her meeting with Turkish Foreign Minister Ahmet Davutaglu in Istanbul. Clinton said she and Davutaglu agreed that a no-fly zone and other assistance the Salafist militias of the FSA “need greater in-depth analysis.”

Though the idea of imposing a no-fly zone sounds rather benign, and oriented at defending civilians, Michael O’Hanlon, a national security and defense policy specialist at the Brookings Institution warned in response to Clinton’s comments that, “You have to consider the slippery-slope phenomenon…how this could evolve from a no-fly zone to a no-go zone” as the Libya intervention did. “If no-fly fails to stop Assad’s attacks,” O’Hanlon warned “then there’s a lot of pressure to strike at Syrian tanks and artillery.”

Clinton later acknowledged during a private speech to investment banking firm Goldman Sachs in 2013 that a no-fly zone in Syria would lead to direct U.S. or NATO intervention that would kill many civilians. She explained that, “To have a no-fly zone you have to take out all of the air defense, many of which are located in populated areas. So our missiles, even if they are standoff missiles so we’re not putting our pilots at risk—you’re going to kill a lot of Syrians…So all of a sudden this intervention that people talk about so glibly becomes an American and NATO involvement where you take a lot of civilians.”

This suggests that the “slippery slope” aspect of a no-fly zone was clearly understood by U.S. planners, and that using the rhetoric of a no-fly zone was simply a way to rebrand what would be a politically unpalatable war of aggression that would kill many civilians as a humanitarian effort to protect civilians.

Another Model for Regime Change

But calls for a no-fly zone as part of a regime change effort in Syria were not new. In 2005, U.S.-based opposition activist Farid Ghadry, a favorite of neoconservative Bush administration officials, described his “practical plan to destabilize Bashar Assad’s rule,” which involved “calling all Syrian opposition groups together for a national conference to create a parliament in exile and draft a new, secular constitution for Syria…Then, take people to [the] streets. Some people get killed. The international community gets further angry at the regime. Then, have NATO forces protect a safe zone in northern Syria…This way we will move right away into Syria.”

Opposition leaders made similar demands for western intervention soon after U.S. planners sparked the anti-government protests in Syria in March 2011, known as the Arab Spring. In September 2011, opposition activist Rami Jarrah (speaking under the pseudonym Alexander Page) was asked what the international community could do to help the opposition. Jarrah replied “Well, what people actually want is pressure on the neighbouring countries so that they might do something and what that may be is international intervention even of a military sort.”

In December 2011, during a bloody battle between the Syrian Army and the FSA’s Farouq Brigades in the Baba Amr neighborhood of Homs, Jarrah appeared on CNN alongside another activist from the city. The activist explained, “We want your help…We just need a no-fly zone, and more pressure on al-Assad’s regime.”

In April 2012, as the fighting in Homs continued, a prominent opposition activist based in Britain, Dr. Mousa al-Kurdi, told al-Jazeera, “Either you defend us, or you arm the Syrian Free Army to defend us. You have the choice.”

Many outside observers have noted that provoking western military intervention, as occurred in Libya, was the opposition’s best strategy to topple the Syrian government. Azmi Bishara, a prominent opposition supporter and al-Jazeera analyst, writes that “A number of [opposition] politicians were betting on international intervention to protect the revolution according to the Libyan model, which was present in their minds.”

Similarly, in June 2011, as the NATO bombing campaign in Libya was already underway, Syria expert David Lesch observed that the fall of Ghaddafi would provide “another model for regime change: that of limited but targeted military support from the West combined with an identifiable rebellion.”

The Libyan capital of Tripoli fell to NATO-backed Islamist militias three months later, on August 28, 2011. Qaddafi was taken captive and brutally murdered (sodomized with a bayonet and then shot in the head) by these same forces on October 20, 2011.

Because of Libya, the Syrian opposition and its regional backers, in particular Saudi Arabia, France, and Turkey, were convinced a U.S.-led intervention was imminent in Syria as well.

Christopher Phillips of Chatham House notes:

“As early as 28 October 2011, activists named a ‘Friday of no fly zone,’ followed by a ‘Friday of the Syrian Buffer Zone’ on 2 December. Leading figures in the SNC [opposition Syrian National Council] such as Burhan Ghalioun and Bassma Kodmani spoke of their preference for military intervention at the beginning of 2012, as if it was a realistic possibility. As rebels formed their militias, many based their strategy on taking sufficient territory not to fully defeat Assad, but to persuade the US to finish him off…the rebels’ regional allies actively encouraged the opposition to expect US military intervention. As Kodmani later recalled, ‘the regional powers were absolutely confident that intervention would happen. Again, Libya had happened, they had participated in the Libya campaign, and they were confident they were going to participate in a campaign in Syria as well.’ She went on, ‘I recall very well, they were always reassuring the opposition “it is coming, it is coming definitely, the intervention is coming.”’…Many regional leaders, particularly Erdogan, believed that the obstacle to US action was domestic: Obama’s campaign for re-election. Turkish officials reportedly told oppositionists to be patient; that intervention would occur after the presidential campaign finished in November 2012.”

This led British historian and Syria expert Patrick Seale to argue in the Guardian that: “The strategy of the armed opposition is to seek to trigger a foreign armed intervention by staging lethal clashes and blaming the resulting carnage on the regime. It knows that, left to itself, its chance of winning is slim.”

Prominent opposition activist Michel Kilo later observed, “We were naïve…people believed the Americans were going to intervene…Encouraged by the West—France in the lead—the insurgents believed it.”

French efforts to promote western military intervention were led by prominent novelist Bernard Henri Levy, who took credit for convincing French President Sarkozy to intervene in Libya in 2011. After the release of a documentary film chronicling Levy’s time embedded with Islamist militants there, AFP commented that “the French people witnessed the unusual spectacle of a notoriously self-promoting leftist intellectual joining forces with a notoriously energetic conservative president to wage war in a distant, sandy nation.” Levy used the release of his film at Cannes in June 2012 to promote his view that, the “successful intervention in Libya can serve as a blueprint” for intervention in Syria. In July 2012 Levy told Saudi-owned al-Arabia that “I think that it is even more doable in Syria than it was in Libya.”

Levy’s appetite for western military intervention was not unique to him but was shared by the French foreign policy establishment generally, which had undergone dramatic change since 2003, when France’s then Foreign Minister, Dominique de Villepin, gave an impassioned speech against the looming U.S. invasion of Iraq. Journalist Alain Gresh observed in Le Monde Diplomatique that since that time, France’s foreign policy has been marked by “a closer strategic alliance with Israel, and shifting toward the American neoconservative position on Iran.” Gresh notes further that the 2012 “election of [Socialist] Francois Hollande to the presidency has changed none of this.”

In August 2012, Levy slammed newly-elected Hollande’s policy on Syria as “too passive,” while explaining that, “The attack plans are ready…Everyone knows it will not take much to deal the [Syrian] regime a death blow. All we need is a pilot.”

However, both Hollande and his appointment for Minister of Foreign Affairs, Laurent Fabius, would later prove to be hawks regarding intervention in Syria. Fabius stated in August 2012, that “Bashar al-Assad does not deserve to be on earth” and in December 2012 that the Syrian wing of al-Qaeda, the “al-Nusra Front is doing a good job.”

Waiting for Washington

Not only French but also British planners were eager to apply the successful Libya model to Syria. As author Nu’man Abd al-Wahid details, it was not the U.S., but rather Britain at the forefront of the NATO intervention in Libya, with British Prime Minister David Cameron and the right-wing UK press castigating President Obama for his hesitancy in authorizing military force. On February 28, 2011 (just 11 days after the beginning of anti-government protests), defense editor of the Times of London, Deborah Haynes, reported that “Britain was ready to use force.” According to the Times, Prime Minister Cameron was “Going further than any other world leader,” and had “ordered General Sir David Richards, the Chief of the Defence Staff, to work on how to impose a no-fly zone in Libyan airspace. Fighter jets would shoot down any encroaching Libyan aircraft…”

The first British cruise missiles were fired, and RAF Tornado warplanes deployed, toward Libyan targets on March 21, 2011. A week later, on March 29, Forbes published a report from the private intelligence firm Stratfor detailing French and British motivations for intervention. Stratfor concluded that although France and Britain already had significant economic ties with the Libyan government, both countries could stand to gain from new, and more pliant, leadership of the country, in the form of additional access to Libya’s plentiful and largely unexplored energy reserves (at the expense of Italian and German energy firms) and by increased weapons sales to any new government there. British Petroleum (BP) was particularly desperate for a stake in Libyan oil production, after facing up to $60 billion in losses from the Macondo oil well disaster in the Gulf of Mexico in 2010. The explosion of BP’s offshore drilling well caused the largest marine oil spill in history, putting BP’s future operations in the United States (and some 25% of its overall oil production) in jeopardy. Stratfor concluded in summary that, “In a sense, France and the United Kingdom are replaying their 19th century roles of colonial European powers looking to project power and protect interests outside the European continent.”

The British role in Libya included not only bombing from the air, but also deploying al-Qaeda affiliated militants to fight on the ground, militants which British intelligence had been harboring in the UK, mostly notably in Manchester, for decades. UK intelligence had partnered with the Libyan Islamic Fighting Group (LIFG), known for fighting in support of Osama bin Laden in Afghanistan, to attempt to assassinate Qaddafi in 1996, and facilitated the travel of LIFG militants from Britain to Libya to fight against Qaddafi in 2011.

After destroying the Libyan state and plunging the country into chaos, General Sir David Richards prepared to implement similar plans in Syria. The Telegraph reports that General Richards prepared a plan for the British army “to build, train and equip a 100,000-strong Syrian rebel army to overthrow President Bashar al-Assad,” and that “Rebels would have been chosen over a 12-month period from groups already fighting the regime, and taken for training to neighbouring Jordan and Turkey, which both support the uprising. Those numbers would then, in theory, have been able to sustain the momentum of an attack on Damascus, particularly if backed by air power provided by the West and friendly Gulf countries. The plan would have been a larger-scale version of the intervention in Libya in 2011…”

These plans likely originated even earlier, in 2009, when French Foreign Minister Roland Dumas was told by top British officials that “they were preparing something in Syria…Britain was organizing an invasion of rebels into Syria. They even asked me, although I was no longer minister for foreign affairs, if I would like to participate.”

British efforts to topple Assad also involved facilitating the flow of al-Qaeda-affiliated militants from Britain to Syria, under the guise of humanitarian convoys. British intelligence relied on the Salafist activist group known as al-Muhajiroun (established in Britain by Syrian cleric Omar Bakri Mohammed) to recruit young Brits of South Asian and Libyan descent to join the jihad in Syria, including many who later joined ISIS. The effort to send British jihadists to Syria was a repeat of what British intelligence had done to support NATO efforts during the Kosovo war in the 1990s.

UK Prime Minister Cameron ultimately called off direct UK military intervention in Syria in 2012, claiming “it would be unsellable to Washington as well as contrary to Parliamentary and public opinion.” This led General Richards complain in 2015 that Cameron didn’t “have the balls” to go through with it.

Operation Volcano

The British intervention that Prime Minister Cameron ultimately failed to authorize was likely planned to complement a major opposition assault on Damascus launched in the summer of 2012.

On Saturday, 14 July 2012, U.S. and Saudi-backed Salafist militias comprising the FSA launched a large offensive to take the Syrian capital, dubbed operation “Damascus Volcano and Syrian Earthquake.” The operation was made possible by weapons shipments organized by U.S. planners two months before. In May 2012, The Washington Post had reported that “Syrian rebels battling the regime of President Bashar al-Assad have begun receiving significantly more and better weapons in recent weeks, an effort paid for by Persian Gulf nations and coordinated in part by the United States, according to opposition activists and U.S. and foreign officials.” The Post noted further that “Materiel is being stockpiled in Damascus” and that according to an opposition figure, “Large shipments have got through…Some areas are loaded with weapons.’”

Reuters notes that the July 14 offensive began when opposition militants attacked Syrian security forces in the Hajar al-Aswad district of southern Damascus, which is adjacent to and south of the Yarmouk Palestinian refugee camp. The operation involved 2,500 fighters, many of which were redeployed from other parts of the country. The fighting spread to three other districts the next day, including the Midan district in the heart of Damascus, with battles flaring within sight of Assad’s presidential palace. Militants hid in narrow alleyways and battled government tanks using rocket-propelled grenades and roadside bombs.

The offensive was highlighted by the bombing of the National Security building in Damascus on July 18, which killed four top Syrian security officials, including the defense minister Dawoud Rajha, national security chief Hisham Ikhtiyar, and Assad’s brother-in-law, deputy defense minister Assef Shawkat.

The New York Times observed that “The attack on the leadership’s inner sanctum as fighting raged in sections of the city for the fourth day suggested that the uprising had reached a decisive moment in the overall struggle for Syria. The battle for the capital, the center of Assad family power, appears to have begun.” FSA leaders claimed the bombing was “a turning point in Syria’s history” and the “beginning of the end” for the government.

Responsibility for the bombing was not immediately clear. A Saudi-sponsored opposition Salafist militia, Liwa al-Islam, led by Zahran Alloush quickly claimed credit. The group issued a statement claiming, “We happily inform the people of Syria and especially the people of the capital that the National Security Bureau, which includes what is called the crisis management cell, has been targeted with an explosive device by the Sayyed al-Shuhada brigade of Liwa al-Islam,” and that “Several regime pillars have been killed.”

Liwa al-Islam, which until September 2012 had fought under the FSA banner, was the most powerful opposition group in the broader Damascus area, with the town of Douma in the Ghouta region serving as its stronghold.

Qassim Saadedine, an FSA spokesman and a prominent commander from the town of Rastan near Homs, claimed credit as well, saying that “This is the volcano we talked about, we have just started.”

Despite the initial apparent opposition success, and with no western intervention forthcoming, the Syrian army was able to repel the offensive, re-taking control of the Midan district of Damascus on July 20, 2012.

Had General Sir David Richards had his way, a British military intervention at this time could have tipped the scales of the conflict and allowed the western and Gulf-backed Salafist militias of the FSA to depose Assad and take Damascus. Cameron refused, however, in part because “it would be unsellable to Washington,” as mentioned above.

An intervention was unsellable at that time because U.S. presidential elections were just three months away. Obama had won the presidency in 2008 in part by feigning an anti-war stance in opposition to the 2003 invasion of Iraq. His hopes of re-election would not be helped by a George Bush-style invasion of another Muslim country, especially considering the chaos that the war had spawned, with hundreds of thousands of Iraqis and thousands of U.S. soldiers killed.

Obama therefore delayed making any major decisions regarding Syria until after securing re-election. For this reason, regional leaders had assured the Syrian opposition that western intervention would occur after the U.S. presidential campaign finished, as mentioned above.

Ludicrous Claims

Shortly after the failed opposition assault on Damascus, Obama declared his famous red line in August 2012. The first attempt to falsely blame the Syrian government for a chemical attack came almost immediately thereafter.

Following a visit to Syria in September 2012, opposition activist Ammar Abdulhamid wrote for the neoconservative Foundation for the Defense of Democracies (FDD) that, “Recently, and following a take-over by rebels of a missile base near Damascus, one of the people affiliated with the old operations room encouraged rebels to claim that some missiles had chemical warheads in the hope that this will show the Americans that their red line was being challenged. The claim, of course, was ludicrous. A statement from the FSA denying this development was made. But the damage was done. The lack of consistent expert advice continues to plague the opposition in every effort they undertake.” That Abulhamid pointed to “one of the people affiliated with the old operations room,” suggests this advice came from a member of a foreign intelligence agency tasked to liaise with opposition militant groups.

The issue of chemical weapons arose again in late November 2012. Israeli officials claimed to have satellite imagery of Syrian troops mixing sarin at two storage sites and filling dozens of 500-pounds bombs that could allegedly be loaded onto airplanes. Obama administration officials were told the sarin-armed planes “could be airborne in less than two hours—too fast for the United States to act, in all likelihood.” According to The New York Times, the incident “renewed debate about whether the West should help the Syrian opposition destroy Mr. Assad’s air force, which he would need to deliver those 500-pound bombs.”

Then-Secretary of Defense and former CIA director Leon Panetta parroted the Israeli claims, stating “I think there is no question that we remain very concerned, very concerned that as the opposition advances, in particular on Damascus, that the regime might very well consider the use of chemical weapons. The intelligence that we have causes serious concerns that this is being considered.”

Opposition leader George Sabra seized on these allegations to demand western military intervention, claiming that Assad would not “hesitate to commit such atrocities as he approaches his inevitable end unless he faces firm and unequivocal international opposition,” and that “We ask the countries of the world to act before disaster hits, not after.”

According to later reporting from journalist Seymour Hersh, the alleged filling of bombs with sarin was the result of activity picked up by a system of on-the-ground sensors used by Israeli and U.S. intelligence to monitor any movement of Syria’s chemical weapon arsenals. Hersh later confirmed that the Syrian government was not preparing for a chemical attack, but simply that the “event was later determined to be part of a series of exercises” and that “all militaries constantly carry out such exercises.”

Chemical Attack in Homs?

Two weeks later, on December 23, 2012, opposition sources claimed that the Syrian army carried out a chemical attack, likely using Sarin, in the city of Homs. Al-Jazeera reported that at least seven people had died after inhaling a poisonous gas “sprayed by government forces in a rebel-held Homs neighbourhood” and that according to Raji Rabbou, an activist in the city, “We don’t know what this gas is but medics are saying it’s something similar to sarin gas.” For the first time, opposition activists also released videos of the casualties from the alleged chemical attack.

Claims of a chemical attack in Homs were apparently reinforced by reporting from journalist Josh Rogin in Foreign Policy. Rogin provided details of an allegedly leaked cable from the U.S. consulate in Istanbul, which supposedly confirmed the use of chemical weapons by the Syrian government after an exhaustive investigation. Rather than sarin, the cables suggested that another chemical, known as Agent 15, or BZ, was used.

The credibility of Rogin’s claims was quickly called into question, however. Tommy Vietor, a White House spokesman, explained that, “The reporting we have seen from media sources regarding alleged chemical weapons incidents in Syria has not been consistent with what we believe to be true about the Syrian chemical weapons program,” while a State Department spokesperson added there was “no credible evidence to corroborate or to confirm that chemical weapons were used” in response to the reporting by Rogin. Additionally, Jeffrey White, a defense fellow at the pro-Israel Washington Institute for Near East Policy (WINEP) said he was also “not convinced” there is credible evidence that Assad’s military had used BZ or any other chemical weapon.

CNN reported on January 16, 2013 that “the concern triggered a more extensive investigation by the State Department” and that the according to a senior U.S. official, the “gas was determined to be a ‘riot control agent’ that was not designed to produce lasting effects…But just like with tear gas, if you breathe in an entire canister, that can have a severe effect on your lungs and other organs…That doesn’t make it a chemical weapon, however.”

Yahoo News similarly reported “If recent media reports have left an impression that Syrian President Bashar Assad might already have used chemical weapons against his own people, think again, says arms expert Jeffrey Lewis. The scholar on weapons of mass destruction is assailing the credibility of Syrian opposition allegations that the chemical ‘Agent 15’ was dispensed in the restive northern city of Homs on Dec. 23.” Lewis, the director the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies’ East Asia Nonproliferation Program at Middlebury College explained that “No one has bothered to mention that Agent 15 doesn’t exist.” Importantly, Lewis noted that “the Istanbul consulate cable was based on accounts by a contractor, Access Research Knowledge or ‘ARK,’ which in turn used a Syrian group known as Basma to interview ‘three contacts’ about the alleged attack.” ARK is in turn funded by the UK foreign office, meaning that, according to Lewis, “These appear to be U.S.- and U.K.-funded groups that produce anti-regime propaganda…Are we really surprised that they are alleging chemical weapons use?”

The role of the UK-funded contractor ARK in promoting false allegations of a chemical attack in Homs is important because it suggests the involvement of British intelligence in seeking to trigger Obama’s red line.

Not only British but also Saudi and French intelligence were promoting questionable evidence of a chemical attack that would trigger the red line. The Wall Street Journal reported that “the Saudis, who have close ties to rebel factions, played an important early role in collecting evidence, Arab diplomats said. This past winter [early 2013], the Saudis flew to the U.K. a Syrian who was suspected of having been exposed to a chemical agent, Arab and European diplomats said. Tests performed in Britain showed the Syrian had been exposed to sarin gas. French and British intelligence agents saw the evidence as credible and stepped up efforts to track other exposures in the chaotic war zone.” However, in contrast to the French, British, and Saudi intelligence services, “U.S. intelligence analysts, particularly those at the Pentagon, were skeptical of those initial results, officials said. Officials said they couldn’t rule out the possibility that the rebels might be planting evidence to try to draw the West into the conflict. They felt they needed a clear ‘chain of custody’ to make determinations. Officials in the White House felt they would need a strong case to present to Mr. Obama, who didn’t want to get drawn into the conflict.”

While momentum was building to blame the Syrian government for a chemical attack, U.S. Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General Martin Dempsey also pushed back against this narrative at the time, arguing that, “I think that Syria must understand by now that the use of chemical weapons is unacceptable. And to that extent, it provides a deterrent value.” Another senior U.S. defense official also noted that, “I think the Russians understood this is the one thing that could get us to intervene in the war.” In other words, there was no doubt on all sides who would benefit from the Syrian government carrying out a chemical attack, and it was not the Syrian government.

Khan al-Assal

A few months later, the issue of chemical weapons emerged once again. On March 19, 2013, a rocket containing chemicals was fired at the town of Khan al-Assal, in Aleppo province in northern Syria. According to the UK-funded Syrian observatory for Human Rights (SOHR), the attack killed 25, including, crucially, 16 Syrian soldiers.

Because Syrian soldiers had been killed, this suggested opposition militant groups were responsible. However, opposition sources quickly claimed the government had carried out the attack instead. The pro-opposition Aleppo Media Centre, which, as journalist Vanessa Beeley details, received funding from the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs, claimed that there had been cases of “suffocation and poison’” among civilians in Khan al-Assal after a surface-to-surface missile was fired at the town and that it was “most likely” due to the use of “poisonous gases” by the Syrian government.

Abd al-Jabbar al-Akaidi, head of the FSA’s Aleppo Military Council and a close contact of U.S. Ambassador to Syria Robert Ford, claimed he had witnessed the attack, and that it was not a surface-to-surface missile, but “an errant strike on a government-controlled neighborhood by Syrian warplanes flying at high altitude.”

U.S. officials also sought to deflect blame from the opposition. Martin Chulov of the Guardian reported that, “Washington, which has for the past six months claimed that only the use of chemical weapons could lead it to overturn its opposition to direct intervention in Syria, later said it had ‘no reason to believe’ rebels had been responsible, but was studying claims that the regime may have been.”

Claims of Syrian government responsibility were immediately dubious, however, as it would mean the Syrian government had done the “one thing” that could get the U.S. to intervene, while entrusting the operation to military commanders inept enough to accidentally kill 16 of their own soldiers in the process.

Assad’s Slam Dunk

The Syrian government itself felt that opposition responsibility was clear and sent a letter to UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon the very next day, March 20, requesting the UN “conduct a specialized, impartial and independent investigation of the alleged [chemical] incident.” Ban Ki-moon quickly agreed to launch an investigation, and appointed Swedish professor Ake Sellstrom, a former weapons inspector in Iraq, as its head on March 26.

However, as open-source analyst Adam Larson details, western diplomats immediately sought to torpedo the Syrian government request to objectively investigate the Khan al-Assal incident. British and French diplomats promptly demanded that the investigation focus not only on the March 19 attack in Khan al-Assal, but also on other alleged chemical attacks that might be blamed on the Syrian government. These included the December 23, 2012, incident in Homs discussed above, as well as a new claim of a Syrian government chemical attack in the Damascus suburb of Ataybah, which also allegedly took place on March 19, 2013.

The New York Times reported that, “Britain and France have written separately to Secretary General Ban Ki-moon of the United Nations that there is credible information suggesting Syria’s government has used chemical weapons in the civil war on multiple occasions since last December,” and that there had been “an exchange of letters with the secretary general starting on March 25 about the information, which they would not reveal in detail.” Despite the British and French request, UN spokesman Martin Nesirky stated on March 26 that “work is already well under way so that the mission can be dispatched quickly.”

But by April 8, 2013, Ki-moon had accepted the British and French request and “urged the Syrian government to accept an expanded UN probe into alleged chemical weapons use, saying he had concluded that an alleged attack in Homs in December warrants investigation.”

Syria’s representative to the UN, Bashar al-Jaafari, claimed that an agreement had already been reached four days before, on April 4, with the UN’s disarmament head Angela Kane, a former German diplomat and World Bank official, to deploy the UN mission only to Khan al-Assal. According to Jaafari, “Kane then went back on the agreement…and delivered a letter the next day contrary to the previous agreement.” Kane justified this by claiming to have received new information about the December 23, 2012, alleged chemical attack in Homs, and that this increased the urgency of investigating not only the Khan al-Assal allegations, but the Homs allegations as well. Syrian state TV noted that “Al-Jaafari wondered how the UN Secretary General could have new information available to him” so suddenly of an incident that had already taken place months ago.

By insisting that other alleged chemical attacks be included in the UN investigation, British, French, and now UN diplomats were attempting to muddy the waters of the investigation. They apparently understood that any independent investigation focusing solely on the Khan al-Assal chemical attack would clearly implicate the western-back opposition, and therefore the investigation had to be expanded to include additional alleged attacks of dubious credibility but that could still be blamed on the Syrian government.

If both sides could be blamed for perpetrating chemical attacks, opposition responsibility for Khan al-Assal could be diluted, and western military intervention could still be justified by suggesting the government was also guilty of having used chemical weapons. The French and British diplomats were clearly grasping at straws by demanding the Homs incident be included, considering that that the U.S. State Department and Pentagon had already dismissed allegations against the Syrian government in that case as baseless, as discussed above.

Additionally, if the claims of a chemical attack in Homs had been credible, why did British and French diplomats wait to request the UN investigate them only immediately after the Syrian government made such a request regarding Khan al-Assal? This shows the British and French demands were a political ploy. Unsurprisingly, when the Ake Sellstrom-led UN mission later reached Syria in August 2013, it declined to investigate the Homs attack. It was not one of the alleged attacks for which there was sufficient credible information to merit further investigation.

Blaming the Victims

While discussing the controversy surrounding the pending investigation of the Khan al-Assal attack, Leslie Gelb of the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR) noted a historical precedent for just this diplomatic tactic. Gelb explains that after helping Saddam Hussain carry out chemical attacks against both Iran and Iraq’s rebellious Kurdish population during the Iran-Iraq war in the 1980s, U.S. diplomats sought to also blame Iran for chemical weapon attacks against Iraq, despite having no evidence to do so.

Gelb’s comments are shocking and worth quoting at length. He recalled:

“…the little matter of America’s great ally in the 1980s, Saddam Hussein, depositing chemical bombs and artillery shells upon human waves of Iranians who were overrunning Iraqi troops in a war that Iraq started. Estimates of how many Iranians were killed by Saddam’s chemicals alone range from 50 to 100,000. What did the Reagan administration do about this? After Saddam’s first mustard gas attacks, Reagan dispatched special envoy Donald Rumsfeld to Baghdad to cement closer ties with the dictator. The Reagan entourage committed a further moral outrage following Saddam’s use of chemicals against the Kurdish rebels in Halabja in 1988, during the closing days of the Iran-Iraq War. Nearly 7,000 Kurds were killed, and thousands more severely wounded, the vast majority of them civilians. Washington’s response was to try and place the blame for Halabja on Iran. Throughout the war, the Reagan team blocked United Nations action against Iraq. After Halabja, it took seven weeks of back and forth before the U.S. finally agreed to a Security Council resolution condemning ‘the continued use of chemical weapons in the conflict between Iran and Iraq’ and expecting ‘both sides to refrain from the future use of chemical weapons in accordance with their obligations under the Geneva Protocol.’ In other words, the resolution implicated Iran as well as Iraq, even though no evidence was produced proving Tehran’s culpability. Let’s face facts. Our nation’s leaders wanted Iran’s defeat and were prepared to accept almost any behavior by Saddam that furthered that goal [emphasis mine].”

Gelb notes further that the secretary of state at that time, George Shultz, admitted years later, “’It’s a very hard balance. They’re using chemical weapons, so you want them to stop using the chemical weapons. At the same time, you don’t want to see Iran win the war.’ Think about that kind of honesty regarding Syria. I believe Assad is probably guilty of the crime, but history shows that evidence could pop up a year or so hence that the jihadi rebels planted the chemicals to foment western military action against Damascus.”

Gelb concluded by saying that, “The screamers for U.S. military intervention [in Syria] are gaining traction,” and that it will be difficult to “stop the hordes for long.”

As Adam Larson details further, there was an additional objective of the French and British demands for an expanded UN investigation in Syria, namely the attempt to impose an all-pervasive chemical weapons inspection regime on the country comparable to that imposed on Iraq in the years preceding the 2003 US invasion.

On April 27, 2013, Syrian information minister Omran al-Zouabi claimed for example that by broadening the scope of the Khan al-Assal investigation to include additional sites and attacks, the aim of the western powers was, “first, to cover those who are really behind use of chemical weapons in Khan al-Assal, and secondly, to repeat Iraq’s scenario, to pave the way for other investigation inspections. To provide, based on their results, maps, photos of rockets and other fabricated materials to the UN, which as we know, opened the way to the occupation of Iraq.”

Russian foreign ministry spokesman Aleksandr Lukashevich similarly explained that the UN Secretary-General Ki-moon’s initial reaction to Syria’s appeal for an investigation was positive, but quickly “underwent a drastic change under the influence of a number of states,” aimed at the “establishment of a permanent mechanism for inspection throughout Syrian territory with unlimited access to everywhere,” as was imposed on Iraq.

Syrian and Russian fears were not unfounded. As The Washington Post reported in 1999, “United States intelligence services infiltrated agents and espionage equipment for three years into United Nations arms control teams in Iraq to eavesdrop on the Iraqi military without the knowledge of the U.N. agency that it used to disguise its work.”

The resultant Syrian government rejection of the revised and expanded investigation proposal therefore delayed the launch of the investigation. This allowed State Department spokesman Patrick Ventrell to deflect culpability away from the so-called rebels and redirect it toward the Syrian government, arguing that “if the regime has nothing to hide, they should let the U.N. investigators in immediately so we can get to the bottom of this” and determine “whether or not the president’s red line has been crossed.”

The delay in the deployment of Ake Sellstrom’s team to investigate the Khan al-Assal attack in turn allowed British and French intelligence additional time to manufacture new dubious claims of Syrian government chemical use that could be added to the baseless December 2012 allegation from Homs.

Sheikh Maqsoud

In the wake of the March 19 Khan al-Assal attack, and the efforts by British and French diplomats to muddy the investigation of it, came another dubious alleged chemical attack that again was blamed on the Syrian government. This occurred on April 13, 2013, in the majority Kurdish Aleppo suburb of Sheikh Maqsoud. According to testimony obtained by the UN Human Rights Council Commission of Inquiry, “the alleged incident affected 21 persons and caused one death. The victims were allegedly transported to a hospital in Afrin for treatment.”

The Sheikh Maqsoud attack was first reported four days later, on April 17, in an article published by ABC News. The article was written however by journalists Mohammed Sergie and Karen Leigh from a separate news site, Syria Deeply.

The report was based on testimony from two people, an alleged survivor, Yasser [no last name given], and a doctor who treated Yasser and other alleged victims of the attack, Dr. Hassan [no first name given].

Yasser claimed that “I heard something explode on the roof. I thought it was a shell and called my brother for help.” After his two infant sons began hyperventilating, he says, “I knew then that there were chemicals in the air and I told everyone to get out. I screamed for help and saw my neighbors come in,” before becoming dizzy and falling to the ground. Yasser explains further that, “I saw my wife nearby; I crawled over to her and hugged her. Then I woke up in Afrin.”

The report then states that Yasser was “recounting the horror he experienced while recuperating at a hospital in Afrin, north of Aleppo. He hasn’t been told that his wife and children are dead, as his doctors don’t think he can handle the shock in his fragile state.”

Dr. Hassan, the director of the hospital in Afrin, explained that “he didn’t have evidence about who was responsible for the attack in Sheikh Maqsood or what kind of chemical was released. But he said the symptoms and treatment clearly indicate that chemical agents caused the deaths of a woman and two children [Yasser’s wife and children] and injured more than a dozen people.” Dr. Hassan also treated the patients with atropine.

Dr. Hassan’s claims of a chemical attack were reinforced in the ABC News report by comments from Hamish de Bretton-Gordon, a British chemical weapons expert. De Bretton-Gordon explained that “On Sunday, we saw a number of reports that those three people were killed in Aleppo. We were sent a load of photos, a load of stuff. The symptoms that were described would be similar to nerve agent poisoning, and the use of atropine would have been an effective method to treat these people.”

De Bretton-Gordon also introduced the idea that perhaps the opposition and government were both guilty of using chemicals weapons, consistent with the strategy of the British and French diplomats who wanted to expand the UN investigation beyond Khan al-Assal, as described above. De Bretton-Gordon speculated that it was likely that improvised chemical weapons had been used (rather than military grade) by both sides, “by the regime to show that the opposition are using chemical weapons, and by the opposition to show that the regime is using them. Obviously if the regime is using them, then a red line is crossed and things are changed.” There was however no mention of a red line if the opposition was found to be using chemical weapons.

The Sheikh Maqsoud attack made bigger headlines after an almost identical story was published about it in the Times of London two weeks later, on April 26, 2013, relying on the same two witnesses, Yasser Younis and Dr. Kawa Hassan [full names provided]. The story was written by journalist Anthony Loyd, who reported that according to Yasser, a chemical munition was dropped on his home in the middle of the night that began emitting poison gas. Yasser claimed that, “My vision was going. I grabbed my boy Sadiq and ran for the street. Then I collapsed. I remember nothing more.” He then woke up in a hospital in Afrin, four hours later. His wife and two sons had already died in the attack.

Anthony Loyd also claimed that his investigation for the Times of London “suggests that nerve gas is being used in Syria’s war.” De Bretton-Gordon was once again quoted to give the nerve gas claim credibility. He gave a bizarre reason for why the government would use chemical weapons, speculating, “As far as the regime go, they are prepared to follow the thickness of the red line to test its boundaries.” The Syrian government of course had no incentive to cross the red line, nor to even test its boundaries.

Claims of the attack were accompanied by video of other alleged victims who had been transported to the hospital. Loyd reports that “Subsequent video footage taken by the medical staff at the hospital in Afrin, an hour’s drive from Aleppo, provided even more compelling evidence. Provided to The Times by Dr Kawa Hassan, an orthopaedic surgeon who received the first casualties at about 4am, it shows victims, among them Yasser and his dying wife, frothing at the mouth and nose in a trance-like state.”

When comparing the ABC News and Times of London accounts, two things seem odd and suggest that Yasser Younis had fabricated at least parts of his testimony. Recall that in the ABC account, Younis became dizzy and fell to ground, then crawled to his wife to hug her before passing out. He then woke up in the hospital in Afrin.

In contrast, in the Times of London account, Yasser claims that he escaped to the street with one of his infant suns before passing out, after which he woke up in Afrin.

Anthony Loyd opens the article by writing that had Yasser “not managed to struggle out of the doorway of his home in Aleppo on to the street in the darkness of night, clutching his infant son to his chest, no one might have ever known what wiped out the family.” Of course, it is not possible that both accounts are true.

It is hard to imagine that Yasser and other witnesses could have misremembered such dramatic details. Whether he gave his wife a final hug before her death on the floor of his home, or he heroically tried to save his dying son while running out the street, both accounts appear meant to give additional emotional impact to his narrative of events. The ABC account provides further dramatic flair. As mentioned above, while lying in his hospital bed in Afrin, Yasser had not yet been told his wife and two sons had died. It is unlikely a victim of a chemical attack would be speaking with journalists before he had even been notified of his family having been killed. These oddities suggest that Yasser may have fabricated his testimony.

“Especially Rebel Forces”

Doubts about the veracity of Anthony Loyd’s report in the Times of London report quickly emerged. Journalist Tracey Shelton of the Global Post (James Foley’s employer) visited Sheikh Maqsoud three days after the incident, on April 16, 2013, to try to confirm rumors that chemical weapons had been used. Shelton was reporting at the time from a nearby neighborhood in Aleppo and was able to walk to Sheikh Maqsoud and speak with the Kurdish police that first responded to the scene at Yasser’s home. She then traveled to Afrin to interview Dr. Kawa Hassan, the other subject of both the ABC and Times of London reports. She tried to locate Yasser Younis, but he had allegedly traveled to a small village that could not be reached safely. Shelton was nevertheless excited to possibly confirm the story of the chemical attack because she knew it would be a world changing story, if confirmed. She was cautious however because, “In Syria at that time, because chemical attacks were this red line, anything that remotely looked as if it could involve any kind of chemical would be labeled instantly as a chemical attack…everybody wanted to prove that this is chemical weapons, because then maybe the U.S. would come in and help them. Especially rebel forces.”

Shelton concluded, however, that Sheikh Maqsoud was a case of a “horrific chemical weapons attack that probably wasn’t a chemical weapons attack” because the symptoms one would expect to see in the victims simply were not present. Shelton reported that, “The telltale sign of a sarin gas attack is myosis, or constricting of the pupils,” but that she and the Global Post were unable to confirm any of them had myosis.”

Experts soon contradicted the claims of the ABC and Times of London reports as well, suggesting that the video of victims at the hospital provided to the Times appeared to be staged.

Elliott Higgins, an open-source investigator for Bellingcat, a group which has received funding from the CIA-cutout National Endowment for Democracy (NED), asked several chemical weapons experts about the video of the victims in the hospital to see if opposition claims appeared credible.

Higgins first queried a consultant from the private threat intelligence firm Allen Vanguard, who noted that in the video:

“None of the people in the hospital are wearing IPE (individual protective equipment); they are not being affected by the same condition as the patient on the stretcher. The first ‘victim’ is not in pain and does not have any visible symptoms beyond a non-moving fresh thin, white trail of foam leading down his face from each nostril. This is not a recognised symptom of nerve agent attack and the early signs (pinpointing of pupils, running nose, tight chest & difficulty of breathing) are absent…The presence of a camera person, lack of IPE worn by the staff, lack of general panic and lack of recognised symptoms amongst the ‘victims’ makes me think that the event has been staged. The symptoms that have been presented have probably been elaborated with single applications of foam; the foam has stopped emerging by the time the camera is shown at them.”

Higgins also queried Steve Johnson, Deputy Editor of CBRNe World, a magazine devoted to responding to chemical, biological, radiological, nuclear or explosives (CBRNe) threats or incidents. Johnson observed that, “I can see ER room chaos and an extremely unusual foaming at the mouth. Doubly unusual as the person, despite being able to move makes no attempt to remove it. No solid conclusions one way or the other could be made from this video. Although it does raise a suspicion of faking symptoms with the highly uniform, highly white foam.”

Finally, Higgins queried Hamish de Bretton-Gordon, who, as mentioned above, had already provided statements in support of the claim that a chemical weapon had been used in Sheikh Maqsoud. Referring to the video showing victims from the alleged Sheikh Maqsoud attack, Higgins asked de Bretton-Gordon, “In your opinion would you be able to draw any solid conclusions about the chemical agent used from the information in that video alone?” De Bretton-Gordon responded, “Not really, there are some inconsistent symptoms with nerve Agent poisoning in this attack. There is however some evidence to suggest that this attack is where the samples that the UK and US Govts and others, analysis comes from, which reported microscope traces of Sarin.”

In the Times of London account, Anthony Loyd notes that Dr. Kawa Hassan had provided him the hospital video. If the videos were staged, as suggested by the experts quoted above, this suggests that, like Yasser, Dr. Hassan may have fabricated his testimony to falsely suggest a government sarin attack. While speaking with Tracey Shelton, Dr. Hassan had indicated that he was convinced sarin had been used. Such a fabrication would not be surprising, given that, as mentioned above, “everybody wanted to prove that this is chemical weapons, because then maybe the US would come in and help them. Especially rebel forces.”

In addition to the videos, images of white, handheld canisters with small holes also emerged, which according to opposition activists had been used to deliver the chemical agent in Sheikh Maqsoud. Elsewhere, other pictures had also emerged of an opposition fighter, from the Nusra Front, with the same type of canister attached to his tactical vest. Higgins asked these experts about the white canister as well.

Regarding the image of the hand-held white canister, the Allen Vanguard consultant observed that “Only the third ‘victim’ has recognisable symptoms of a chemical attack but even so, it is unlikely that a blood agent would be dispersed using a hand thrown canister because of the unreliability of the container and risk to the thrower of being contaminated by the blood agent.” Of the white hand-held canister, the Allen Vanguard consultant commented that “the canister is totally unsuitable to disperse a chemical or biological attack. An attacker would be more inclined to use cheaper, more conventional weapons (such as a grenade or rifle) if they were in such close proximity to their enemy.”

Of the image of the Nusra Front fighter with the same canister attached to his tactical vest, Steven Johnson of CBRNe commented, “Notably the man with it on his vest had no apparent protective equipment. Which suggests it’s more likely to be smoke or a riot control agent.” Johnson concluded by rhetorically asking, “would you trust your ability to throw a nerve agent to keep you safe? [emphasis mine]”

Whose Samples?

De Bretton Gordon had knowledge of the source of the samples from Sheikh Maqsoud that were provided to the UK and U.S. governments because he himself had provided them. By his own later admission, de Bretton-Gordon was engaged in a covert effort to smuggle soil samples out of Sheikh Maqsoud and to produce media reports about the alleged attack there. Journalist Kit Klarenberg reports that de Bretton-Gordon, who previously claimed to be a member of the 77th Brigade, the British Army’s official psychological warfare division, and who has been identified in the British press as a former spy, explained during an interview in 2014 that, ‘In March last year [2013] there was a reported sarin attack in Sheikh al-Maqsood and I helped the Times—chap called Anthony Lloyd who very sadly got shot two weeks ago – to cover this story and tried to get samples to the UK for analysis…I won’t go into the details of that.’”

In short, a British intelligence asset, de Bretton-Gordon, helped to plant a story in the UK press and provided samples to the UK government of unknown origin, to prove an alleged chemical attack for which there is clear video evidence of staging. This “evidence” was then used by US and UK officials to claim that the Syrian government had crossed Obama’s red line.

While de-Bretton Gordon provided samples to the UK government, a U.S.-funded medical NGO provided samples from Sheikh Maqsoud to the U.S. government. Andrew Loyd reports in the Times of London that according to local medical sources, “in the immediate aftermath of the attack a team from ‘an American medical agency’ arrived at the hospital in Afrin. They took hair samples from the casualties for testing at ‘an American laboratory.’”

Loyd notes these samples led U.S. Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel to suggest that “the Syrian regime had probably used chemical weapons, specifically sarin gas, on a small scale.”

CNN journalist Christiane Amanpour reports that the medical agency collecting these samples was the Syrian American Medical Society (SAMS), led by Dr. Zaher Sahloul. SAMs was not an independent, non-political, humanitarian organization, however. Dr. Sahloul himself campaigned strongly for U.S. military intervention in Syria. In the summer of 2013, Sahloul met with Obama at the White House for an Iftar dinner, in which he delivered a letter to the president urging him to establish a no-fly zone in Syria.

As journalist Max Blumenthal later reported, SAMS has functioned as an arm of the U.S. foreign policy establishment to promote regime change in Syria. SAMS received millions in funding from USAID, which boasts its own Office of Transition Initiatives to promote regime change in target countries, while former USAID staffers David Lillie and Tony Kronfli were among SAMS’ directors. The group later played a key role in laundering false reports of Syrian government chemical attacks, in Khan Sheikhoun in 2017 and Douma in 2018. A former SAMS employee characterized the group to Blumenthal as “Al Qaeda’s MASH unit.”

British and U.S. claims of Syrian government sarin use in Sheikh Maqsoud were accompanied by similar accusations from Israeli intelligence. During a national security conference in Tel Aviv on April 23, 2013, a senior Israeli military intelligence official, Brigadier General Itai Brun, had claimed that “To the best of our professional understanding, the regime used lethal chemical weapons against the militants in a series of incidents over the past months, including the relatively famous [Khan al-Assal] incident of March 19…Shrunken pupils, foaming at the mouth and other signs indicate, in our view, that lethal chemical weapons were used.” Brun’s evidence included “photographs taken of the area after the attacks” indicating sarin use.

Reuters reported on April 26, 2013, however, that experts from the UN’s Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) made clear that the evidence claimed by the U.S. and Israel did not meet UN standards, and that the OPCW would only issue a judgement about the use of chemical weapons if inspectors were able to visit the site directly to collect soil, blood, urine and tissue samples, maintain custody of the samples, and examine them in certified laboratories.

The issue of chain of custody was particularly important. OPCW spokesman Michael Luhan explained that even if samples were made available to the OPCW by the U.S. and Israel, the organization could not use them because, “The OPCW would never get involved in testing samples that our own inspectors don’t gather in the field, because we need to maintain chain of custody of samples from the field to the lab to ensure their integrity.” If samples were collected by opposition activists, journalists, or western intelligence agencies and then provided to the OPCW, it would be impossible to ensure that the samples came from the site of the attack in question and had not been manipulated for political purposes.

Despite the lack of any credible evidence for a chemical attack in Sheikh Maqsoud, The Washington Post reported that Israeli military officials claimed on April 23, 2013 that “Assad’s forces had used chemical weapons on several occasions to kill dozens of so-called rebel fighters. They said the evidence made them ‘nearly 100 percent certain.’” The Post reported further that on April 25, 2013, the Obama administration had mimicked Israeli claims, suggesting that the “Syrian government is likely to have used chemical weapons on a small scale against its own people,” despite the fact that, the “administration provided no evidence in public…saying only that its conclusion was partly based on ‘physiological’ data.”

The New York Times was also skeptical, with the paper’s editorial board noting on April 24, 2013, that while Assad “may be capable of using weapons of mass destruction, there is no proof that he has done so,” and that “…the case against Mr. Assad, so far, is thin.” The NYT noted further that “Israel, Britain and France have not offered physical proof (Israeli officials cited only photographs of Syrians ‘foaming at the mouth,’)” and that even “Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu of Israel told Secretary of State John Kerry on Tuesday that he ‘was not in a position to confirm’ his own government’s intelligence assessment.”

Unsurprisingly, when the Ake Sellstrom-led UN mission later reached Syria in August 2013, it attempted to investigate the Sheikh Maqsoud attack, but was not able to corroborate the allegation that chemical weapons were used.

It should be noted here that western and Israeli intelligence and diplomatic officials did not appear particularly concerned to generate credible allegations of Syrian government chemical weapons use. Quantity rather than quality of claims was sufficient to create the perception of Assad’s guilt, so long as these were repeated regularly in the western press. When videos began to emerge of a massive chemical attack in Ghouta in August 2013, a narrative was already firmly in place suggesting Assad was responsible.

Saraqeb

The staged chemical attack on April 13, 2013 in Sheikh Maqsoud was quickly followed by additional allegations, this time in the town of Saraqeb, in Idlib province, on April 29, 2013.

The BBC reported that the Syrian army had bombarded Saraqeb with artillery, and that according to local doctors, one woman named Maryam Khatib had died in the attack while eight others were admitted to the hospital suffering from breathing problems, vomiting, and had constricted pupils. BBC journalist Ian Pannell visited Saraqeb two weeks later. He was shown videos of the alleged chemical attack by opposition activists, and interviewed the dead woman’s son, who explained that “It was a horrible, suffocating smell. You couldn’t breathe at all. You’d feel like you were dead. You couldn’t even see. I couldn’t see anything for three or four days.”

In this case, opposition sources claimed the government had used the same hand-held grenade-like devices used in Sheikh Maqsoud, but this time enclosed in a concrete casing and allegedly dropped by helicopter. The BBC noted further that, “One device was said to have landed on the outskirts of Saraqeb, with eyewitnesses describing a box-like container with a hollow concrete casing inside. In another video, a rebel fighter holds a canister said to be hidden inside the devices. Witnesses claim there were two in each container. Another video shows parts of a canister on the ground, surrounded by white powder.”

The evidence for a chemical attack carried out by the Syrian government in Saraqeb was just as weak as in the case of Sheikh Maqsoud, given that the same type of canister was used in both locations. As noted above, the security experts consulted by Elliott Higgins concluded that the canisters likely contained only riot control agents such as tear gas, and had previously only been seen in the possession of opposition fighters from the al-Qaeda affiliated Nusra Front, who saw no need to wear protective equipment when handling them.

Tracey Shelton, who investigated the Sheikh Maqsoud claims, also reported that Turkish doctors had tested the blood of victims of the alleged attack in Saraqeb, but that no sign of sarin was detected and the tests “did not find anything unusual.”

Despite this, French foreign minister Laurent Fabious later claimed the opposite, that samples taken by a local medical team in Saraqeb and sent to French intelligence had tested positive for sarin. The samples were taken from four alleged victims who were treated in a field hospital run by the France-based Union of Syrian Medical Relief Organisations (UOSSM). The samples included those from Maryam Khatib, who died after being transported to a hospital in Turkey.

Among the UOSSM doctors allegedly treating victims was a British-Syrian oncologist named Mousa al-Kurdi. He described Maryam Khatib “as completely unconscious, some evidence of froth on her mouth, no surgical injury whatsoever…red eyes, very hot…muscle twitching [and] I’ve never seen pupils so constricted, almost non-existent.”

Like SAMS in Sheik Maqsoud, Al-Kurdi was not a neutral and objective source. Al-Kurdi had helped coordinate medical logistics from inside Syria in the early days of the war and was involved politically with the western-backed political opposition, the Syrian National Council (SNC). As noted above, Al-Kurdi appeared on al-Jazeera in April 2012 to make a special appeal to the international community: “Either you defend us or you arm the Syrian Free Army to defend us. You have the choice.”

It is an odd coincidence that a well-known British-Syrian doctor happened to be in Saraqeb at just this moment. Al-Kurdi was able to treat victims and give testimony of an alleged chemical attack which could have triggered the very foreign military intervention he had openly been calling for.

It should be noted that Ian Pannell was the BBC reporter relaying the claims of opposition activists in Saraqeb of a chemical attack. This is significant because, as journalist Robert Stuart details, Pannell helped stage another fake chemical attack a few months later, with the help of al-Kurdi’s daughter, another British-Syrian doctor named Rola Hallam, which will be discussed below.

Stopping the Hordes

In the wake of Khan al-Assal, Sheikh Maqsoud, and Saraqeb, the “hordes” Leslie Gelb had warned about included not only neoconservative Republicans, but also liberal interventionist Democrats. On April 26, 2013, Anne-Marie Slaughter, a Princeton academic and the former director of policy planning during Hillary Clinton’s term as secretary of state, published an op-ed in The Washington Post arguing that any reluctance to intervene in the Middle East caused by the 2003 Iraq war must be forgotten because “U.S. credibility is on the line,” and that if Obama did not intervene in Syria, “The world would see Syrian civilians rolling on the ground, foaming at the mouth, dying by the thousands while the United States stands by.” Slaughter cited the fabricated claims of chemical weapons use in Homs in December 2012 as proof the Syrian government had crossed the red line, while claiming further that, “Similar evidence has been squelched again and again, until finally our allies—the British, the French and even the Israelis—forced our hand.” Slaughter’s long-standing affiliation with the Aspen Institute suggests she was expressing the view of a prominent faction within the U.S. intelligence services.

Slaughter’s effort to pressure Obama to intervene was reinforced as well by New York Times columnist and former executive editor Bill Keller two weeks later. Keller also argued that the lessons of the Iraq war must be ignored (“Syria is not Iraq”) while trying to shame Obama into launching an intervention. Keller recommended escalating weapons shipments to the so-called rebels, and that if Assad still refused to step down, “we send missiles against his military installations until he, or more likely those around him, calculate that they should sue for peace.” Keller stressed the risks of inaction, including “the danger that if we stay away now, we will get drawn in later (and bigger), when, for example, a desperate Assad drops Sarin on a Damascus suburb.”

Both Slaughter and Keller displayed a curiously prescient knowledge of the alleged attack in Ghouta four months later (“The world would see Syrian civilians rolling on the ground, foaming at the mouth, dying by the thousands,” and “a desperate Assad drops Sarin on a Damascus suburb”).

Whose Sarin?

Just as pro-intervention propaganda intensified in the U.S. press, Syrian government claims about opposition use of sarin in Khan al-Assal in March 2013 were bolstered, in this case by the conclusions of Carla del Ponte, a member of the UN’s Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic and a former war crimes prosecutor. The Telegraph quoted del Ponte on May 6, 2013 as explaining that “According to the testimonies we have gathered, the rebels have used chemical weapons, making use of sarin gas…We still have to deepen our investigation, verify and confirm (the findings) through new witness testimony, but according to what we have established so far, it is at the moment opponents of the regime who are using sarin gas [emphasis mine].”