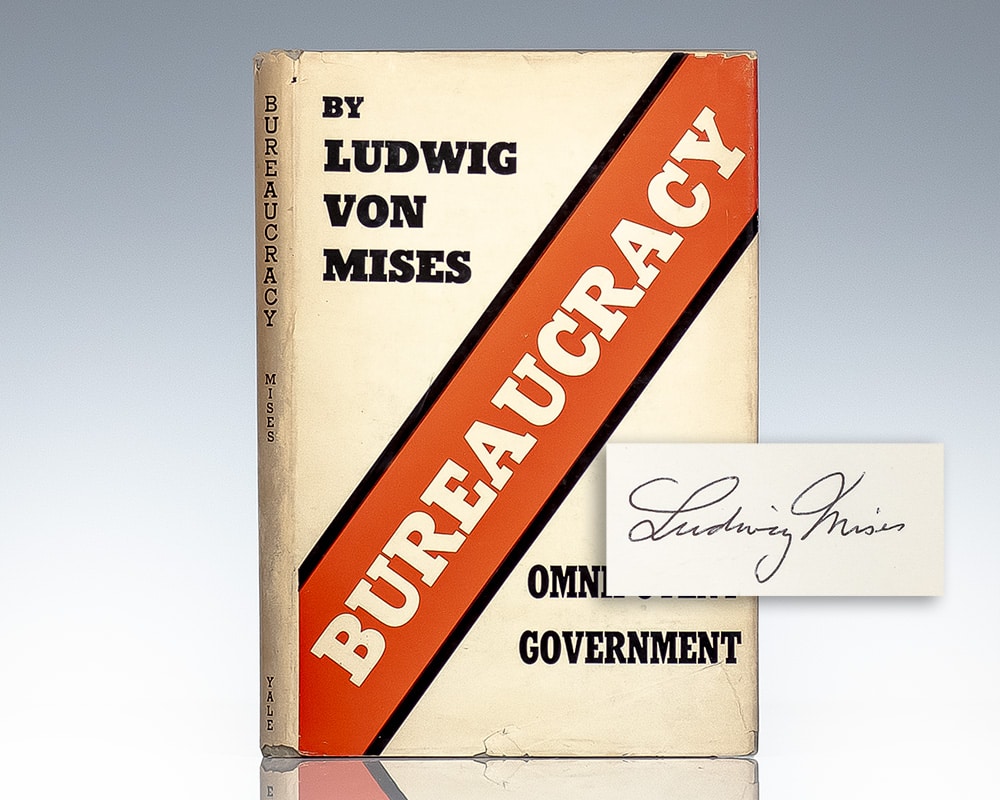

With all the talk about government efficiency, it would be useful to remind ourselves why bureaucracies differ radically from for-profit businesses. Ludwig von Mises devoted a short but enlightening volume to this subject in 1944, Bureaucracy. Elon Musk and Vivek Ramaswamy, who will co-chair the nongovernmental Department of Government Efficiency, should do some homework by reading that book.

Mises, as an advocate of limited government, did not argue that bureaucracy has no place in a free society. In contrast to anarcho-capitalists, he thought government and therefore some bureaucracy was necessary to protect what he valued most: peaceful social cooperation through the division of labor—that is, the market economy. Violence against persons and property was clearly antithetical to the continuing welfare-enhancing collaboration we call the market process. But Mises did not want bureaucracies trying to do what free, private, and competitive enterprises could do better. Moreover, if the government went beyond its mere peacekeeping duties, it would undermine the market process and make us all less well off despite any good intentions.

Mises began by reminding readers (or perhaps teaching them from scratch) what the free market is and what it accomplishes. It’s a great primer for those who lack the time to read his longer works. He wrote:

Capitalism or market economy is that system of social cooperation and division of labor that is based on private ownership of the means of production. The material factors of production are owned by individual citizens, the capitalists and the landowners. The plants and the farms are operated by the entrepreneurs and the farmers, that is, by individuals or associations of individuals who either themselves own the capital and the soil or have borrowed or rented them from the owners. Free enterprise is the characteristic feature of capitalism. The objective of every enterpriser—whether businessman or farmer—is to make profit.

The uninitiated might ask who runs things. He replied: “The capitalists, the enterprisers, and the farmers are instrumental in the conduct of economic affairs. They are at the helm and steer the ship.”

However, let’s not jump to conclusions about who really runs things, Mises advsed:

But [the capitalists, etc.] are not free to shape [the ship’s] course. They are not supreme, they are steersmen only, bound to obey unconditionally the captain’s orders. The captain is the consumer.

Neither the capitalists nor the entrepreneurs nor the farmers determine what has to be produced. The consumers do that. The producers do not produce for their own consumption but for the market. They are intent on selling their products. If the consumers do not buy the goods offered to them, the businessman cannot recover the outlays made. He loses his money. If he fails to adjust his procedure to the wishes of the consumers, he will very soon be removed from his eminent position at the helm. Other men who did better in satisfying the demand of the consumers replace him.

All the conventional controversy about bosses and workers overlooks the critical point:

The real bosses, in the capitalist system of market economy, are the consumers. They, by their buying and by their abstention from buying, decide who should own the capital and run the plants. They determine what should be produced and in what quantity and quality. Their attitudes result either in profit or in loss for the enterpriser. They make poor men rich and rich men poor. They are no easy bosses.

Capitalism is not a profit system, Mises taught. It is a profit-and-loss system. If the consumers give thumbs down to a product, the entrepreneur could lose everything. He may have to seek a job from a superior entrepreneur.

The performance of businesses, Mises wrote, can be appraised only because private property in the means of production, free exchange, and the resulting money prices permit economic calculation and thus planning by economizing individuals. This was Mises’s pathbreaking demolition of the economic case for central planning—socialism in its national and international forms—over a century ago.

Economic calculation matters when comparing a business to a bureaucracy. As Mises wrote:

The manager of the whole [business] concern hands over an aggregate to the newly appointed branch manager and gives him one directive only: Make profits. This order, the observance of which is continuously checked by the accounts, is sufficient to make the branch a subservient part of the whole concern and to give to its manager’s action the direction aimed at by the central manager….

As success or failure to attain this end can be ascertained by accounting not only for the whole business concern but also for any of its parts, it is feasible to decentralize both management and accountability without jeopardizing the unity of operations and the attainment of their goal. Responsibility can be divided. There is no need to limit the discretion of subordinates by any rules or regulations other than that underlying all business activities, namely, to render their operations profitable.

What about a bureaucracy? The answer is implicit in what has already been stated. By nature a bureaucracy faces no profit-and-loss test. It has money expenses in a market-oriented society: it hires willing workers and buys equipment and supplies from willing vendors. However, it does not offer its output to potential consumers, that is, people who are free to say no and take their money elsewhere. Instead of consumers, a bureaucracy has taxpayers, who must pay whether they want the output or not. This disconnect must have far-ranging consequences. (Government services for which user fees are charged differ in this respect, but the government typically forbids competition.)

Instead of the business directive “Make profits,” Mises wrote:

Bureaucratic management is management bound to comply with detailed rules and regulations fixed by the authority of a superior body. The task of the bureaucrat is to perform what these rules and regulations order him to do. His discretion to act according to his own best conviction is seriously restricted by them….

The absence of the seller-buyer relationship makes a big difference:

The objectives of public administration cannot be measured in monetary terms and cannot be checked by accountancy methods…. In public administration there is no connection between revenue and expenditure….

In public administration there is no market price for achievements….

Now we are in a position to provide a definition of bureaucratic management: Bureaucratic management is the method applied in the conduct of administrative affairs the result of which has no cash value on the market. Remember: We do not say that a successful handling of public affairs has no value, but that it has no price on the market, that its value cannot be realized in a market transaction and consequently cannot be expressed in terms of money….

Bureaucratic management is management of affairs which cannot be checked by economic calculation.

This would be a valuable lesson for Musk and Ramaswamy to take to heart. Their task should not be primarily to search for ways to make the bureaucracies more efficient. Rather their task ought to be to identify those current functions the government should not be performing, those that should be turned over to free, private, profit-motivated, and competitive enterprise. We ought to replace coercion with consent.

We must, in other words, revisit the question: what is the proper role of government, if any, in a society that aspires to be free?