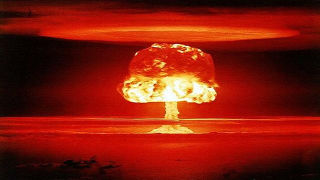

Leave it to Donald Trump to threaten to rain “fire and fury” on the North Korean people the same week the world observed the 72nd anniversary of the U.S. government’s vindictive atomic bombings of Japanese civilians. In case anyone missed the message, Defense Secretary James “Mad Dog” Mattis warned that the Kim Jong-un regime’s actions risk the “destruction of its people.” He wasn’t talking about Kim’s cruel communism.

We know what Trump and Mattis mean, even if many conservatives twist themselves like pretzels to transform the threatened savagery into something more benign. Trump and Mattis were referring to America’s nuclear arsenal.

Trump promised “fire and fury like the world has never seen.” No one would expect him to know this, but the North Korean people have seen their share of fire and fury at the hands of the U.S military. It happened almost 70 years ago, when Harry Truman, another president who went ga-ga over generals, unleashed America’s savage vengeance during the Korean War. It’s called the “forgotten war,” but even when it wasn’t forgotten, few Americans realized how brutally the United States treated people that posed no threat whatever to Americans.

How many know that, quoting historian Bruce Cumings, “far more napalm was dropped on Korea [than on Vietnam] and with much more devastating effect, since the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) had many more populous cities and urban industrial installations than North Vietnam…. By late August [1950] B-29 formations were dropping 800 tons a day on the North. Much of it was pure napalm. From June to late October 1950, B-29s unloaded 866,914 gallons of napalm.” It was also known as “jellied gasoline.” Regarding its effect on the human body, Cumings quotes the survivor of a “friendly fire” attack on Americans: “Men all around me were burned. They lay rolling in the snow. Men I knew, marched and fought with begged me to shoot them…. It was terrible. Where the napalm had burned the skin to a crisp, it would be peeled back from the face, arms, legs … like fried potato chips.”

Cumings adds:

George Barrett of the New York Times had found “a macabre tribute to the totality of modern war” in a village near Anyang, in South Korea: “The inhabitants throughout the village and in the fields were caught and killed and kept the exact postures they held when the napalm struck — a man about to get on his bicycle, 50 boys and girls playing in an orphanage, a housewife strangely unmarked, holding in her hand a page torn from a Sears-Roebuck catalogue crayoned at Mail Order No 3,811,294 for a $2.98 ‘bewitching bed jacket — coral’.” US Secretary of State Dean Acheson wanted censorship authorities notified about this kind of “sensationalised reporting,” so it could be stopped.

Thus the war that is also known as a “limited police action” was anything but. Cumings writes that “From November 1950, General Douglas MacArthur ordered that a wasteland be created between the fighting front and the Chinese border, destroying from the air every ‘installation, factory, city, and village’ over thousands of square miles of North Korean territory.”

Gen. MacArthur presented his own impressions of the early results at a congressional hearing in May 1951 after Truman fired him:

The war in Korean has already almost destroyed that nation of 20,000,000 people. I have never seen such devastation. I have never seen, I guess, as much blood and disaster as any living man, and it just curdled my stomach, the last time I was there. After I looked at the wreckage and those thousands of women and children and everything, I vomited. If you go on indefinitely, you are perpetuating a slaughter such as I have never heard of in the history of mankind. [Quoted in Napalm: An American Biography by Robert M. Neer, 2013.]

Air Force Chief of Staff Curtis LeMay, in an oral history quoted by Cumings, said that “over a period of three years or so … we burned down every town in North Korea and South Korea, too.” (Quoted in Cumings’s preface to the 1988 edition of I.F. Stone’s The Hidden History of the Korean War:1950-1951.)

“To think,” Cumings writes, “that the American Air Force could have dropped oceans of napalm and other incendiaries on cities and towns in North Korea, leaving a legacy of deep bitterness palpable four decades later, and that this was done in the name of a conflict now called ‘the forgotten war’ — as memory confronts amnesia, we ask, who are the sane of this world?”

Americans know nothing of this, but you can bet the people of North Korea know it. They may be ruled in the harshest dehumanizing way by Kim Jong-un, but they still have their humanity.

This devastation was wreaked by so-called conventional weapons. No nuclear weapons were used, as they had been only a few years earlier in nearby Japan. But this is not to say their use was not contemplated.

The Truman war council discussed using atomic bombs just two weeks after the war started, Cumings writes. “At this point, however, the JCS [Joint Chiefs of Staff] rejected use of the bomb because targets large enough to require atomic weapons were lacking; because of concerns about world opinion five years after Hiroshima; and because the JCS expected the tide of battle to be reversed by conventional military means. But that calculation changed when large numbers of Chinese troops entered the war in October and November 1950.”

Then Truman publicly threatened to use all weapons at America’s disposal. “The threat was not the faux pas many assumed it to be,” Cumings writes, “but was based on contingency planning to use the bomb. On that same day, Air Force General George Stratemeyer sent an order to General Hoyt Vandenberg that the Strategic Air Command should be put on warning, ‘to be prepared to dispatch without delay medium bomb groups to the Far East…. [T]his augmentation should include atomic capabilities.'”

Cumings notes:

The US came closest to using atomic weapons in April 1951, when Truman removed MacArthur. Although much related to this episode is still classified, it is now clear that Truman did not remove MacArthur simply because of his repeated insubordination, but because he wanted a reliable commander on the scene should Washington decide to use nuclear weapons.

Of course, what were then called “novel weapons” were not used in Korea. Yet, Cumings writes, “without even using such novel weapons — although napalm was very new — the air war levelled North Korea and killed millions of civilians. North Koreans tell you that for three years they faced a daily threat of being burned with napalm: ‘You couldn’t escape it,’ one told me in 1981. By 1952 just about everything in northern and central Korea had been completely levelled. What was left of the population survived in caves.'”

Let’s remember that the war never formally ended, and repeated calls by the North Korean government for a peace treaty and nonaggression pact have largely fallen on deaf American ears.

We don’t know if victims would be able to tell if they’d been nuked or napalmed. What we do know is that Trump seems willing to commit the most monstrous crime in our names. Let’s hope it’s empty bluster.

Related reading

“Talk to, Don’t Provoke, North Korea”

“The War Party Talks Nonsense on Korea”