Here’s a good idea: let’s not go to war against Russia. Let’s not even rattle a saber at Russia (or China, for that matter) because even wars that no one really wants can be blundered into. Many losers would be left in the aftermath, even if nuclear weapons were kept out of sight, but no one would win. So as that smart Defense Department computer says in the 1983 movie WarGames, “The only winning move is not to play.”

The crisis du jour is Ukraine; before that, it was Georgia, both former Soviet republics. For some inexplicable reason, Russia’s rulers get nervous when the U.S. foreign policy elite treats Russian historical security concerns as of no consequence. Could it have something to do with the several invasions of Russia through Eastern Europe in the past? Jeez, from the way the irrational Russians behave, you’d think their American counterparts never invoked U.S. security concerns (usually bogus) as a reason for military action. As if…

But maybe it is time for America’s rulers to take Russian worries into consideration. Even for those of us who are no fans of Vladimir Putin and the government he runs, this seems like good advice – if for no other reason than narrow American self-interest. At least, that’s how it looks from the view of regular Americans, who might appreciate for a change what Adam Smith described as “peace, easy taxes, and a tolerable administration of justice.”

Anyone who has paid attention to U.S. foreign policy since the peaceful dissolution of the Soviet Union and its Warsaw Pact alliance, 1989-91, would realize that America’s bipartisan foreign-policy elite has taken precisely the wrong tack by baiting nervous Russian nationalists at every turn. Despite promises to the contrary, that elite has led the charge to add members to the NATO alliance, taking the anti-Soviet military and political organization right up to the Russian border and staging military exercises uncomfortably close. The U.S. has also sold weapons systems to NATO-member Poland, formerly a member of the Warsaw Pact.

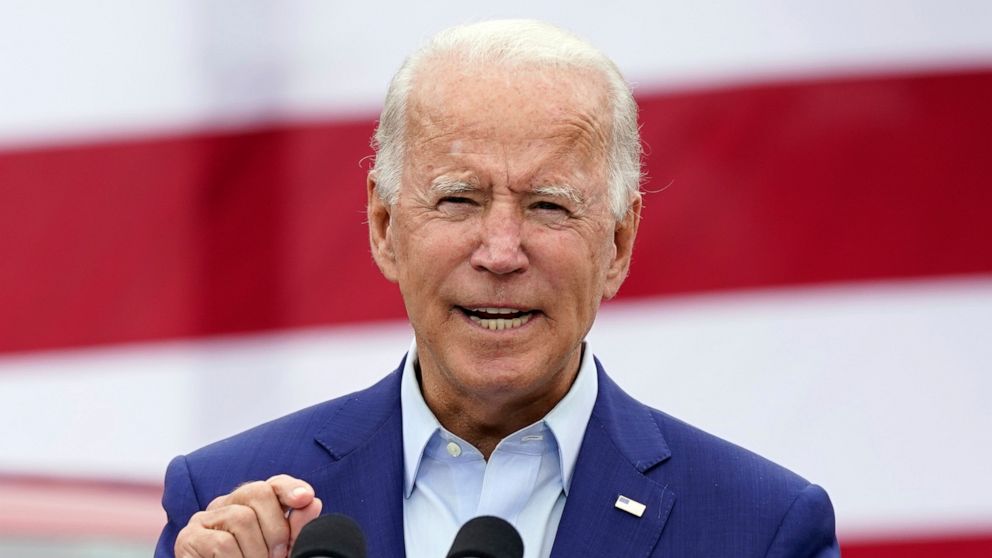

Putin insists that NATO not expand any further, but Biden told him to shut up. The U.S. position is that NATO’s inclusion of former Soviet possessions is purely an alliance affair. Meanwhile, Biden threatens more harsh economic sanctions and even more U.S. troops to Eastern Europe if Putin doesn’t acquiesce by, among other things, moving his troops away from the Russia-Ukraine border

Let’s also recall that in 2014 the U.S. stood behind a neo-Nazi-supported coup against an elected, Russian-friendly president in Ukraine, knowing full well how the Russians would react. Fearing U.S./NATO encroachment, Putin’s government annexed Crimea with its strategic warm-water Black Sea naval base, which has been part of the Russian security system for over 200 years. Nevertheless, and most relevant to today’s heightened tensions, Putin declined an opportunity to annex eastern Ukraine (the Donbass region full of ethnic Russians ) when a majority there voted for independence from Kiev.

You didn’t have to know too much about European history to see how provocative the U.S.-sponsored regime change in Ukraine would be. To make matters worse, Ukraine and Georgia have become de facto NATO members, but only because the U.S. elite has not yet convinced its European counterparts to give those two former Soviet republics official membership. That, however, hasn’t stopped Washington from extending a security guarantee to Ukraine that is all too much like the one that NATO members extend to one another. Biden has just reinforced that guarantee.

Which Americans are ready to die for Kiev?

For some reason it’s easy for Americans, who can be as nationalistically self-centered as anyone, to assume that any ratcheting up of tensions with Russia must be the Russians’ fault. The establishment media have no problem presenting this as an indisputable fact. But how do they know it’s true? They never furnish evidence. Foreign-policy expert Ted Galen Carpenter of the Cato Institute has a much more evidence-bound take:

Moscow’s behavior has been more a reaction to aggressive moves that the United States and its Ukrainian client have already taken than it is evidence of offensive intent. Russian leaders have viewed the steady expansion of NATO’s membership and military presence eastward toward Russia’s border since the late 1990s suspiciously and they have considered Washington’s growing strategic love affair with Kiev as especially provocative.

Moreover, Carpenter adds,

Ukraine’s own policies have become dangerously bellicose. The government’s official security doctrine adopted earlier this year, for example, focuses on retaking Crimea, the peninsula that Russia annexed in 2014 following the West’s campaign that helped demonstrators overthrow Ukraine’s elected, pro-Russian president. Statements by President Volodymyr Zelensky and other leaders have been disturbingly bellicose, and Ukraine’s own military deployments have further destabilized an already fragile situation.

Carpenter points out that while the United States is far more powerful than Russia in conventional terms, “unless the United States and its allies are willing to wage an all-out war against Russia, an armed conflict confined to Ukraine (and perhaps some adjacent territories), would diminish much of that advantage. Russian forces would be operating close to home, with relatively short supply and communications lines. US forces would be operating far from home with extremely stressed lines. In other words, there is no certainty that the US would prevail in such a conflict.”

Would the Biden administration then back down or go nuclear? Who is eager to find out?

Those considerations aside, the U.S. government should simply stop fanning the Russophobic flames simply because a war would be incredibly stupid.