Great part of that order which reigns among mankind is not the effect of government. It has its origin in the principles of society and the natural constitution of man. It existed prior to government, and would exist if the formality of government was abolished.

–Thomas Paine, Rights of Man, 1792

Sometimes an idea that at first sounds nuts isn’t really nuts at all. Case in point: the market-anarchist principle that people should be free to buy the law and protection they want in the market.

Even a subscriber to Murray Rothbard’s anarcho-capitalism might raise an eyebrow because Rothbard formulated a libertarian law code that he expected would be carried out in a market-anarchist society. In contrast, the market-for-law market anarchist doesn’t see things that way. How would a single code even be implemented? It’s not as if libertarians agree on everything. Think of intellectual property, abortion, defamation, and more.

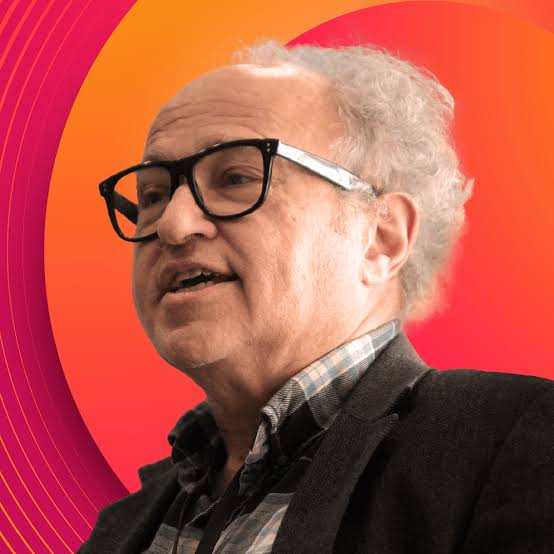

David Friedman, a veteran anarcho-capitalist, explicitly favors a market in law, not just in police and arbitration (that is, court) services. Here’s how Friedman describes it in The Machinery of Freedom (chapter 29; free pdf here):

In such an anarchist society, who would make the laws? On what basis would the private arbitrator decide what acts were criminal and what their punishments should be? The answer is that systems of law would be produced for profit on the open market, just as books and bras are produced today. There could be competition among different brands of law just as there is competition among different brands of cars.

In such a society there might be many courts and even many legal systems. Each pair of rights enforcement agencies agree in advance on which court they will use in case of conflict. Thus the laws under which a particular case is decided are determined implicitly by advance agreement between the agencies whose customers are involved. In principle, there could be a different court and a different set of laws for every pair of agencies. In practice, many agencies would probably find it convenient to patronize the same courts, and many courts might find it convenient to adopt identical, or nearly identical, systems of law in order to simplify matters for their customers.

As Friedman sees things, individuals would not directly choose among the competing arbitration firms. They would choose defense firms according to the services offered. Those firms would typically have contracted with others about which arbitration firms they would use if their clients were in a conflict. (Insurance companies already do this.) Customers of course would know about this and would choose defensive firms partly on that basis. The defense firms and arbitrators want to attract customers. These are profit-seekers, remember. Also remember that individuals are customers here, not taxpayers or subjects — an important distinction.

The incentives to submit to and abide by binding arbitration without state-backing would be strong. A defense firm or a customer known for ignoring adverse rulings would have problems doing business in the future. This is the “discipline of constant dealings,” Friedman writes. Its powerful influence cannot be ignored. Even now, it plays out everywhere. It is not mainly due to the state that people generally keep their contracts and even less formal promises. The government did not make eBay or the credit card a success. Rating systems are powerful. What Friedman has in mind is essentially an enlargement of the function of the ubiquitous contract, which creates obligations — law, really — for the parties, with binding arbitration by a specified agency in any dispute. (If the government didn’t have the power to overturn arbitrators’ rulings, this private alternative to courts would be even bigger than it is now.)

Wouldn’t the defense firms simply fight when their clients had a conflict? That’s what many people expect. But why expect it? Friedman reminds us that violence is costly in many ways, even for the winners. Understandably, it’s not the business way of thinking. For one thing, a firm would have to pay its employees a steep hazard premium, raising its costs above those of competitors willing to negotiate.

Is this a perfect arrangement? No, but what other earthy arrangement could be perfect when it consists of fallible people all the way down? (See last week’s TGIF, “Limited Government’s Bait and Switch.”) Governments have hardly been a guarantee of individual liberty. Think about the United States!

It’s not impossible that everyone in an area who intends to commit murder or theft will patronize a defense firm that protects rights violators. But how likely is that to succeed? Most people don’t plan on murdering or stealing and would buy protection against the few that might. (The streets, etc., would be private, remember.) Even would-be criminals don’t want to be killed or stolen from. But what about states that commit murder, even mass murder, and theft, as they often have? What’s the recourse?

Further, the objection that defensive firms might get together and become a new state also falls short. If people get used to seeing themselves as customers, they won’t want to be turned back into taxpayers and subjects. Ideology matters. Friedman writes in chapter 36:

Anarchist institutions cannot guarantee that protectors will never become rulers, but they decrease the power that protectors have separately or together and they put at the head of rights enforcement agencies men who are less likely than politicians to regard theft as a congenial profession.

Some will object that law and the protection of rights and freedom should not be matters for bargaining. But what’s the alternative? Who could seriously deny that all political systems entail bargaining? This is true even of a constitutionally limited government conceived by explicit champions of individual freedom. The Constitutional Convention in 1787 featured bargaining. So did the earlier deliberations over the Declaration of Independence and the Articles of Confederation. Even small groups rarely are of one mind. But we’re not talking about small groups.

Obviously, bargaining goes on every day: between legislators, between legislators and constituents, and between the legislative and executive branches. It goes on among Supreme Court justices. Political campaigns are a form of bargaining.

Where there are people and scarce resources, there is disagreement and therefore bargaining. It’s the human condition. Better that people negotiate and enter defense contracts they choose than submit to a state monopoly: in politics, unlike the market, bargaining has victims, namely, the mass of people who had no real say. In the market, individuals make the deals that best fit their circumstances.

So a market for law isn’t so crazy after all. It sounds great. Remember, market incentives and political incentives are entirely different. In the market, individuals choose knowing that what they choose is what they will get and that the costs and benefits will fall mostly on themselves. So they tend to make reasonably informed decisions.

In the political “market,” individuals get one impotent vote each, which means that the candidate (policy set) they “choose” is not necessarily what they will get and that even if they get what they want, each voter knows he will experience only a tiny part of the total benefits and costs. The rest will fall on a large group of other people. Under those circumstances, few people have any incentive to choose in an informed way.

Finally, we may wonder whether the market would tend to produce pro-liberty laws. After all, maybe lots of people will want something else, like alcohol prohibition. Again, we can’t have guarantees, no matter the system. But liberty has something in its favor: a pro-freedom asymmetry. Namely, people would probably be willing to pay more to protect their private lives from busybodies than others would be willing to pay to run other people’s lives. The prohibitionists would have to foot the whole bill all by themselves. There would be no taxpayers.

Friedman gets the last word (chapter 31): “People who want to control other people’s lives are rarely eager to pay for the privilege; they usually expect to be paid for the services they provide for their victims…. For that reason the laws of an anarcho-capitalist society should be heavily biased toward freedom.”

Also see:

John Hasnas, “Toward an Empirical Theory of Natural Rights.”

Edward P. Stringham, ed., Anarchy and the Law: The Political Economy of Choice (an anthology that contains a debate on market anarchism’s practicality and stability).