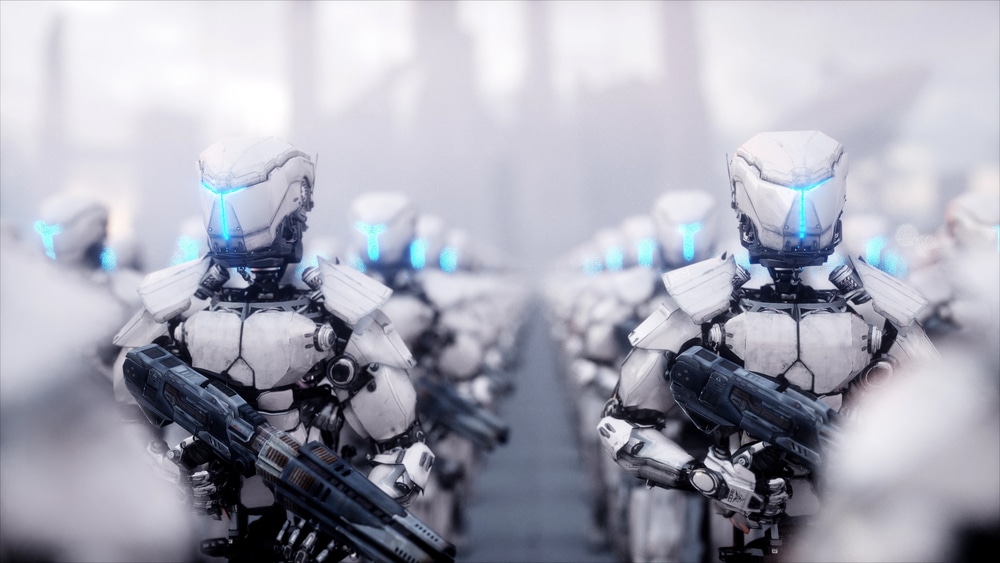

A new documentary film, Unknown: Killer Robots (2023), directed by Jesse Sweet and available on Netflix, addresses some of the perhaps surprising developments in artificial intelligence weaponry—above all, the specter of autonomous lethal aircraft systems programmed to kill on command and then permitted to act independently, with no human being “in the loop.” In some ways, this represents a dramatic turning point in the history of warfare, because up until now human beings have always “made the call” in commanding soldiers where, when, why, and whom to kill. The film offers a variety of criticisms and expressions of concern that the use of such lethal technologies could swiftly spin out of control.

There are those who reject out of hand the sorts of worries elicited by provocative films such as Terminator (1984) and Blade Runner (1982), wherein robots and cyborgs eventually set themselves against the species of human beings who created them. Whether or not such dystopic scenarios might one day come to pass, I submit to you that the situation is already out of control, not because of the potential for autopilot machines to run amok, nor because, as the film also reports, it is possible to program a computer to generate the formulas of thousands of highly toxic molecules, which could be adopted as chemical weapons for use by either state or nonstate actors. Rather, the root problem is that the human beings who have managed the use of lethal technologies for states throughout the twenty-first century abandoned long ago the most basic principles of a democratic republic.

Brandon Tseng, a former Navy Seal, is co-founder of Shield A.I., a company striving to develop systems designed to protect soldiers through the use of artificial intelligence. In Unknown: Killer Robots, Tseng describes the extreme danger of clearing buildings in Afghanistan and his fervent desire to find ways to avoid having to send soldiers into “fatal funnels” (the foyers and hallways of structures), where they can be easily ambushed. In demonstrating the thermal capability of NOVA, one of the firm’s machines, a colleague matter-of-factly observes, “If that’s 98.6 degrees, it’s probably a human. People are considered threats until deemed otherwise.” Tseng chimes in, “It is about eliminating the fog of war to make better decisions.”

I was struck by the glibness with which the inversion of the burden of proof was fleetingly articulated as an almost trivial matter of fact. Rather than assume that people are innocent until proven guilty, they are “considered threats until deemed otherwise.” Another of the persons interviewed in the film, Izumi Nakamitsu, the UN High Representative for Disarmament Affairs, who is critical of the rapid expansion of the use of autonomous systems in warfare, laments that we do not know whether machines can distinguish between civilians and combatants. But the far more insidious problem is that those who orchestrated and fought the Global War on Terror did not themselves know how to distinguish civilians from terrorists and shockingly “solved” this problem only by brute stipulation.

We now know, thanks to courageous whistleblower Daniel Hale (currently serving a federal prison sentence), that the U.S. government defined all military-age males located in the places where terrorists were believed to reside as asymmetrical or irregular enemy combatants protected by neither the Geneva Conventions nor the laws of civil society. The uniform-clad warriors simply assumed that every potentially dangerous military-age male in civilian dress located in a place thought to harbor terrorists was “fair game” for targeting. This despite the fact that some, indeed many, of the persons killed throughout this period of history had no prior involvement with jihadists and were justifiably incensed at the invasion and occupation of their lands, and the obnoxious assertion by the U.S. military of the right to kill anyone anywhere for any reason, and to do so with total impunity.

Great strides were made by societies over millennia in rejecting the tyrannical presumption of monarchs to be able to kill at their caprice. When persons altogether oblivious to the significance of that history are tasked with programming the new killing machines, then we should indeed be worried, because the last vestige of moral responsibility serving to rein in state killers to any degree at all will have been eliminated. But as things stand, drone operators and their commanders, who annihilate terrorist suspects through the use of remotely controlled aircraft, already act with effective impunity, for each time that children or other innocent persons are destroyed, the tried-and-true “collateral damage” label is applied, and the deaths are written off as unfortunate but unavoidable, given so-called military exigencies.

The most graphic expression of such an abject insouciance toward human life is currently on display in Israel, where many thousands of residents of Gaza have been systematically slaughtered under the guise of “just war” by the government claiming to target the perpetrators of the crimes of October 7, 2023. The situation in Gaza provides a magnified or concentrated view of the ghastly modus operandi of the U.S. military in the aftermath of the crimes of September 11, 2001. For more than two decades, citizens stood blithely by as their government destroyed the lives of countless human beings throughout the Middle East and in Africa. Many of those persons were located in residential areas or attending events such as weddings, funerals, and other community gatherings, where “bad guys” were presumed to be present. In the light of the massacre of Palestinians currently underway, the U.S. government’s decisive role in normalizing mass homicide against civilian targets under a guise of state security can no longer be denied.

“Freedom is not free!” Tseng and other soldiers, along with their supporters. insist, and perhaps it is true that nothing is free. Certainly the focus upon force protection above all else was paid for, in a sense, by the very disregard for civilian lives seen today in Gaza. Rather than uphold the principle of noncombatant immunity defended, at least nominally, throughout much of the history of what were claimed to be “just wars,” the warriors quietly dropped the principle altogether, preferring to prioritize, above the sanctity of civilian life, the avoidance of friendly fire incidents and allied combatant casualties. “Shoot first, suppress questions later” became the operant rule governing checkpoints in Iraq. In what became a veritable vortex of violence, persons who dared to question the U.S. government’s version of what happened in an endless series of mass homicides were pegged as suspicious. Some were christened “associates” and added to ever-lengthening hit lists.

On viewing Unknown: Killer Robots, I was struck by the failure of anyone in a documentary film ostensibly focusing on the dangers of lethal autonomous weapons systems (deceptively abbreviated LAWS) to notice, much less mention, the most fundamental problem with this new automated capacity to track and kill targets. The problem with what looks to be the latest revolution in military affairs (RMA) is not that the killer robots might wage a war against their makers, which, in theory, could happen, but at this point seems far-fetched. The problem which should concern us at this moment in time, and is underscored by the comportment of the Israeli government against the residents of Gaza, is far more fundamental, and has gone largely unnoticed by politicians and the populace.

The slick marketing line which initially won politicians over to the use of this technology was that lethal drones would minimize the tragic sacrifice of our soldiers. But how was it that the populace itself became inured to the callous disregard for civilian lives championed by the U.S. government since 2001, and which the Israeli government now brazenly displays? Ultimately this casuistic feat was achieved through evading any significant public debate by asserting the necessity of secrecy on national security grounds. The acquiescence of the taxpayers who fund the U.S. drone program was achieved, first and foremost, through the crafty wartime assertion of “state secrets privilege” conjoined with the enlistment of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) to allocate resources and personnel to what was euphemistically termed “kinetic action,” i.e., state-inflicted, extrajudicial execution, specifically in areas unoccupied by the military itself. But by now, the manifest absurdity of the assumption that persons suspected of any crime related to terrorism should be considered automatically guilty no longer appears even to surface as a problem in the minds of those who work in the lethal autonomous weapons industry.

For years, people had no idea what was being done in their name by the drone warriors. But by the time the government began to disclose how extensively lethal drones were being used, not only in war zones but also “outside areas of active hostilities,” the practice of remote-control killing had already been normalized among the “experts” who determine military policy. Most of the persons employed in the killing machine, such as Brandon Tseng, appear to be unaware that they have been brought to act in ways which undermine the very foundations of the republic which they claim to be defending.

A few whistleblowers, such as Daniel Hale and Brandon Bryant, have awakened to the degree to which they were deceived into committing what they now regard as murder. As in the abandonment of the “quaint” principle of noncombatant immunity, the inversion of the burden of proof on suspected future possible terrorists was accomplished quietly, without any public debate. Over more than two decades, citizens were effectively indoctrinated by the Pentagon-infiltrated media to cede to the killers the benefit of the doubt, hence the frequency of the boilerplate report that the latest crop of persons identified as evil actors had been eliminated and the nation bravely defended. Only rarely, in the face of overwhelming evidence, have officials acknowledged that “mistakes were made,” and nearly never has there been any finding of legal or moral culpability, even in cases where dozens of civilians were slaughtered.

The public has never been privy to the procedures used and the basis by which targets are selected for incineration by missiles launched by remotely piloted aircraft, a.k.a. unmanned combat aerial vehicles (UCAVs) or lethal drones, even in cases involving U.S. citizens such as Anwar al-Awlaki and his son, Abdulrahman al-Awlaki. Rather, the killers have appointed themselves the historians of their very own actions, claiming that state-inflicted homicides are legitimate acts of national defense.

The astonishing normalization of extrajudicial execution or assassination (slyly rebranded “targeted killing,” provided only that a missile is the implement of homicide) against suspects identified as potential future terrorists—along with anyone who happens to be in their vicinity—was achieved through the suppression of any and all evidential basis for thousands of drone strikes under cover of the blanket “state secrets privilege.” Government agents have been protected from accountability in each and every case of malfeasance, whether intentional, involuntary, or negligent. Indeed, whenever the official story is finally proven to be false, as in the August 29, 2021, drone strike in Kabul, Afghanistan, which killed ten civilians with no ties to terrorist groups, institutional figureheads briefly express regret that “mistakes were made” while insisting that the perpetrators were acting with good intentions. Having thus effectively exculpated themselves, they then move on to commit the very same “mistakes” all over again.

Given the seemingly perpetual motion of the well-greased gears of the state’s killing machine—in both the United States and Israel—the gravest danger with the complete automation of lethal drone technology is not that robotic devices might somehow run amok and devise their own sinister schemes to take over the world à la a variety of dystopic films. The real problem is that they will be programmed to act upon premises already accepted by the persons who work in the military’s sprawling drone program, which has always aimed to maximize lethality. Arguably, there could be no more dangerous premise for the future of free human beings than the one currently embraced (whether consciously or not) by drone-equipped warriors: that suspects are guilty until proven innocent.

Men such as Brandon Tseng, who fought in the vexed theater of Afghanistan, and were personally affected when some of their comrades were blown up by angry jihadists, rationalize to themselves that the new autonomous weapons systems will save soldiers’ lives. Tseng himself explains that he is motivated primarily by the desire to protect future soldiers just like his comrades who came to ruin during the Global War on Terror. But the normalization of the government’s hyper-lethality and forever wars was ultimately achieved through the use of linguistic legerdemain. The underlying assumption was that wartime necessity made it everywhere and always permissible to kill, even though the former pretext of combatant self-defense had evaporated from every context where there were no troops on the ground to protect.

It is entirely natural for soldiers who have experienced the horrors of war to wish to diminish the incidence of what they themselves have witnessed. But there are layers of self-deception involved in what has become a specious justificatory apparatus for increased state lethality at the expense of civilian life. During the conventional wars of the past, soldiers on the ground (whether conscripts or volunteers) always faced vexing dilemmas in which “kill or be killed” guided their actions, sometimes culminating in the tragic deaths of innocent bystanders. In drone warfare outside areas of active hostilities, in stark contrast, there are no soldiers on the ground to protect, and so the “kill or be killed” pretext no longer exists, except in a form so dilute that it cannot support the claim to necessity. This same specious pretext can be expected to continue seamlessly under conditions of full weapons systems autonomy. As allied soldiers are spared the dangers of close quarters combat through the development and deployment of robotic systems, what formerly were regarded as legitimate acts of killing in self-defense will disappear altogether for the simple reason that machines are not human beings. All that will be left is killing for the sake of killing, delusively claimed by machine programmers to forestall vague and purely hypothetical dangers in the future.

The marked increase in government lethality effected through the use of “smart technology” originally claimed to diminish the tragic loss of innocent life should trouble any objective outsider, but only insiders have a significant say in which policies are implemented. Institutional conservatism ensures that the persons who remain in their positions or advance to higher positions embrace the status quo presumptions of their higher-level colleagues. At some point it appears, at least from within an organization, that everyone agrees with the practices and policies already in place.

The lethality of autonomous weapons systems run by artificial intelligence is a natural concern among persons hoping to draft conventions prohibiting the killing of targets with no human being “in the loop” to “make the call.” In reality, it matters little whether the deadliest of all premises, the presumption of guilt and attendant inversion of the burden of proof, is assumed by human beings or embedded in the algorithmic programming of literal killing machines, for the result for humanity is the same. It may be easier for machines to kill more people faster, given the speed with which their calculations can be carried out, but the moral problem with this procedure is equally grave, no matter who or what selects the targets and launches the missiles.

The ongoing comportment of the Israeli government, while extreme, is simply more blatant than the secretive use of the very same apparatus by the U.S. government during its rampage of killing throughout the Middle East. All twenty-first century U.S. presidents have used drones to annihilate persons pegged as potentially dangerous to the people of the United States, with nary an acknowledgment of the increased danger now faced by persons who happen to live in the vicinity of targeted suspects, whether within or outside declared war zones.

Underlying the use of targeted killing more generally, whether by robots or human beings, is the assumption in evidence—not only in Afghanistan, Iraq, Yemen, Pakistan, Libya, Syria, Mali, and Somalia, but also in Gaza—that the targeted suspects, along with their associated family members, friends, and neighbors, have no rights whatsoever. Those convicted of future potential capital crimes behind closed doors by government analysts are not permitted to defend themselves, to lay down their arms, or even to protest when their names have been mistakenly added to hit lists. So long as the first premises of drone warfare remain in place, having up to now largely evaded critical scrutiny, the robots programmed to kill by algorithms written by persons who already accept the inversion of the burden of proof will simply mimic and likely expand what is demonstrably an immoral, albeit institutionalized, practice. Remote-control killing may have been normalized during the Global War on Terror, but it remains nonetheless highly objectionable from virtually any normative theory of ethics which one considers—with the sole exception of “might makes right,” or moral relativism.

While eliminating altogether the danger of allied combatant casualties at the targeting site, remote-control killing, whether fully automated or directed by human beings, effectively guarantees an increase in the number of innocent people killed. This is because the domain of what is designated permissible military killing has expanded to include areas inhabited primarily by civilians. In truth, the claim that remote-control killing diminishes allied combatant casualties, too, is false, for in many of the areas where lethal drones have been deployed, it is implausible that Congress would ever have ratified the declaration of war needed to send ground troops into those places.

The twenty-first century practice of assassination rebranded as targeted killing has dramatically increased the incidence of “collateral damage,” not only in terms of the first-order killing of civilians, but also second-order effects such as maiming and the manifest blowback of state-provoked terrorism. In other words, even from the limited, amoral perspective of Realpolitik, the so-called smart warriors have failed in their alleged mission to eliminate terrorism, as can be seen in the grisly retaliatory attacks of Hamas, ISIS, et al.