The header image for this article comes from a mural featured at the library of the University of Oregon. It is set to be replaced because of an accusation of being ‘racist’. The incident is a reminder that our intellectual heritage as members of the ‘American race’ is no longer relevant to American intellectuals. Something has been lost.

The forces of progress have created a particular dilemma for modern humanity. All our history, the stability of our societies has been based on evolving, powerful sets of traditions. At the very core of these traditions have been deeply seated religious beliefs held by individuals. These beliefs have provided individuals with a sense of meaning. They have provided a sense of why and how the wider world and universe exist. They have defined our social and family roles, acting as an anchor for our social and emotional lives. Our personal aspirations, our daily moral decision making and our self-directed personal evolution have all been framed by traditions and beliefs. Then, around the 1970s, Western Society just sort of decided, nah, we don’t need this anymore.

We do need religion. Rather, we need something; we need beliefs and tradition. At least, we need the social and philosophical structure that these provide. Even those who do not believe in the literal truth of religion have benefited from religion’s former role in society, so if religion will be discarded, something must replace it. The loss of religion is a dilemma facing all of us.

Western Civilization has become unmoored; nothing is true, nothing can be said to be moral or not, our purpose in life as individuals and groups is ill-defined. The seculars who have discarded religion have not replaced it. The religious have increasingly had to reject secularism, including science and reason, in order to maintain a coherent social order based around the faith-based affirmation of supernatural truths. It hasn’t always been the case that the religious have rejected scientific evidence in order to maintain their worldview. Yet today, these two worlds are necessarily incompatible. Both worlds are missing elements that they need, and both need each other. Tradition was never a monolith, it had the ability to be re-interpreted, and evolve. Progress has never answered the ultimate questions, and has taken for granted the role of tradition in creating social stability. Bridging the gap between the secular and religion is the great task of reclamation for Western Society. Creating a common language of discourse between secularism and belief is the necessary first step to reclaim Western Civilization and save it.

Consider the problems facing the modern moral discourse. There is no common language. The left bounces between idiosyncratic moral crusades based on ever shifting notions of political victimhood. It is a deconstructive paradigm that is unable and unwilling to stake a claim on any kind of truth. It cannot build civilization, only scavenge from its decaying remains. Maybe the left doesn’t need religion, but they do need some sort of moral anchor upon which to build, rather than tear down. Their moral paradigm has no language for this.

Now consider the situation of the religious right. They speak of sin. Sin is part of an old moral language. When everyone spoke this language, we knew that sin was inherently bad. We could debate whether a certain activity was sinful or not, but the idea of what sin is and how we should react to it was universally understood. This is important, because sin isn’t just an abstraction of “bad things we shouldn’t do.” Christian morality also suggests that sinners can repent, and that believers ought to forgive and be kind to the penitent. The language of morality is loaded. Sin includes a belief in a creator who issues moral commandments. The concept doesn’t work for those with a secular world view. As a result, there’s no common language anymore. No wonder politics is so divided, facts be damned, we don’t even have a common basis for communication.

Communication is necessary for society, and therefore morality and ethics. We have no ethics, no politics, no trade and no love, without communication. If society is to operate at a high level – one capable of processing complex moral questions – it must communicate at a high level. Yet, we speak different moral and spiritual languages. The West will be healed when our communication is healed. Thus, I hold that the development of a new framework for communicating about morality and religion is key to a future for the West. The secular and the religious must figure out how to talk to each other once again.

Libertarianism is the right place to start talking about this

There are pressing problems facing the world. You could pick any one and maybe argue that it’s the worst problem we face. War, of course, is a big one. Nuclear war is an existential concern. There are a lot of small problems that innovation could solve, but first we need a functional financial system to coordinate it all. Resources run scarce, so what about developing energy technologies, or finding resources in outer space? After all this, maybe then education, human capital development, is an utmost, pressing concern. There’s the question of demographic decline. Notice, I haven’t even mentioned environmental damage, equity, gender equality, trans rights, racism, reducing traffic, getting people out of cages for having wanted to smoke a plant, and so forth. There are certainly a lot of problems, but only of a few of them can possibly matter the most. Among these, this question of fixing our ability to communicate about and think in moral terms has to be the most important solution upon which all others ultimately depend.

Is religion a libertarian problem to solve? No, but morality and the framework for a common social discourse surrounding it is. Libertarianism is unequivocally the right torch bearer for addressing this topic. Libertarianism is the natural home for this discussion, because it’s the historical home of this discussion. The forceful power of the West, which tore from heaven the fire of gods to create the greatest amelioration of human suffering in the history of mankind, comes from its former ability to promote a balanced discourse between the religious and the secular. Enlightenment society may have rejected religion, but even so, compared to today enlightenment Europe was a deeply religious society. The highest expression of enlightenment ideals, in my opinion, took the form of Anglo-American liberalism. If we reduce classical liberalism to a couple of core ideas, we can see why contemporary Libertarianism may be the only place in modern society where the bridging of secular and religious discourse can occur.

If we reduced Libertarianism/Classical Liberalism to two core functional principles, what would they be? In my opinion, the following works well:

- Moral understanding occurs in the individual

- Moral understanding corresponds to objective forms, and can therefore be communicated in an unbiased way between individual minds.

It has to be noted that many philosophical traditions firmly reject both of the above propositions. Many other traditions are highly skeptical of both. Yet, liberalism – classically – is based in the axiomatic truth of both concepts. Notions ranging from freedom to innovation are based in these two principles. They are also critical to distinguishing contemporary Libertarianism from liberal and conservative beliefs. This can be observed by viewing America as the quintessentially libertarian nation.

Critics of libertarian political ideals claim that there has never been a libertarian society. This isn’t true. There has been at least one, and it was so successful that nobody noticed. One could argue that America, particularly Yankeedom from 1750-1850, was a libertarian society.

Consider how Yankee America during this time featured a mix of Native American, African American, German, Dutch, East Anglish, Welsh, Scotch, French, Cornish, and other diverse cultures all colliding. There had never been so strong a collision and mix of religious fervor and speculation since ancient times, with multiple Awakenings and burnt-over districts where Methodist, Jew, Episcopal, Presbyterian, Mennonite, Millerite, Shaker, Quaker, and more all shared a mostly peaceful coexistence. Has there ever been such a confluence of diversity of thought, belief, and ethnic background, in an environment of so little government supervision, with an equivalent level of not only peace, but explosive progress? When America did fight wars, it was when huge political stakes became involved, and the heavy hand of imperial prerogatives stepped in. The North never hated the South for its particular creeds, only for the perceived (unfairly perhaps) apathy the South had towards those creeds, in allowing slavery. Slavery, in turn, leading to war only after becoming a political issue. It was a war which many if not most of the abolitionist strongly opposed.

There is a particular philosophy associated with the 1750s, which in turn had a noted decline from after the 1840s. This dominant American philosophy came from the British Enlightenment. However, the enlightenment influence in Britain went a few different ways. In Scotland, Presbyterian religiosity and common sense folk tradition combined to lead to what is called the Scottish Enlightenment. A famous practitioner of this tradition is Thomas Reid, creator of the school of Common Sense Realism. These ideas mingled with branches of the English Enlightenment leading to a particular school of thought called the Christian Enlightenment.

In Northern England, famous thinker Joseph Priestly vigorously advanced the ideals of the Christian Enlightenment. Not only was the man the discoverer of Oxygen, he also was a preacher with a church congregation, and thinker of religion and philosophy. His core belief was that religion and science could be held in perfect harmony, and that each should seek to evolve in ways to facilitate that harmony. The value of this idea, whether or not it’s correct, is that reason improves belief and belief improves reason. Today, the two merely fight, and retrench against each other.

In America, the “liberals”, later “Unitarians”, advanced this tradition of harmony between reason and belief. It was the ideas of the liberals, spreading during the Great Awakening of 1750, that taught New England of the value of liberty and paved the way for 1776.

It might seem that science and religion are not, in fact, in harmony. This is certainly the major cause for the decline of Christian Enlightenment ideals starting around the 1850s. As practitioners lost hope in the dream of discovering a framework for this harmony, they turned to continental advances in thought. American boys would go to Europe to get fancy “Doctor of Philosophy” degrees, steeped in German ideas critiquing much of the British Enlightenment, promoting what would become nationalism and modernism, but at first championing a kind of non-rational romanticism.

In context, the American Christian Enlightenment represents a true third strain of Anglo-American politics. If framed according to the clash between reason and belief, the Anglo-American tradition can be divided into three persistent strains. For convenience, these can be accurately labeled according to contemporary terms: conservative, liberal, and libertarian. Conservatism seeks to empower traditional authority. Liberalism seeks to empower intellectual authority. Libertarianism seeks to empower individual authority, where reason and belief exist in a balance of power. Proto-libertarianism, explicitly in the form of the Christian Enlightenment, dominated early America.

If we classify Anglo-American political traditions into the three categories of liberal, conservative, and libertarian, we can observe that they have existed for a long time, and that only the libertarian strain is absolute in its commitment to the two core principles of classical liberalism previously mentioned. This is why a common language of discourse between the secular and religious is necessary to achieve a libertarian consensus, since traditional and intellectual authority must be balanced against each other for individual authority to reign.

The Anglo-American conservative tradition has the fatal flaw of hedging against liberty. I think British, especially American, conservatism is relatively liberal. There is a belief in free inquiry associated with the tradition. What “Paleo-Conservative” belief embraces is the value of the wisdom embedded in tradition. Given the stability tradition provides, this wisdom is clearly valuable. Morality is framed by tradition. However, conservatism tries to absolve itself of the obligation to sort out which parts of tradition contain which gems of wisdom. They say, “Don’t throw the baby out with the bathwater,” but if we have identified the baby, there’s no reason to keep the dirty bathwater. As the bathwater grows increasingly tepid, and grimy, conservatives want to dive deeper into the bath. The authority of tradition is more important to them than the content of tradition.

Consider the awful state of conservative religion in the USA. More and more, churches cater to modern culture, playing Rock’N’Roll which has nothing to do with God. Rock is great, but that’s why you go to concerts. Church is for something else. Isn’t a balance between the two, facilitated by keeping them in separate spheres where they can each be the best at what they are, preferable? Nope, contemporary Christians fill their halls with bizarre charismatic worship set to bad rock music – is this going to solve America’s moral problems, and create a new common language of discourse? Whatever works for people personally, I can’t criticize, but I see religion turning to more and more desperate measures. Shouting, screaming, drums and guitars, hoping that the countervailing pressures of modern culture will be shut out, and somehow in the mix the spirit of God will be let in.

On the other hand, highly conservative religious communities are increasingly admitting that national media, educational institutions, and so forth are antagonistic to religion and Christianity in particular. Change and accommodation isn’t enough, some churches have committed to isolating themselves. Yeah, they can ignore society’s problem, and they’ve surely bought enough guns to put their money where their mouth is in that respect. However, by cutting off from fellow man they’ve also ensured their private little societies will no longer progress. The tools of reason and truth given by God, ostensibly, will no longer serve to improve human life, and draw society closer to Him. All that will remain is the tyranny of stale tradition. How sad.

Inevitably, the isolationism of the religious right will fail. No matter how well you teach your kids the Bible, no matter how successfully you isolate them from popular media, your grandkids will eventually jump headfirst into the sin – and the problems – of modern society. Isn’t the Christian religion a mandate to evangelize society? To heal the sick, feed the hungry and so forth? Don’t the liberals have spiritual needs that the righteous have a duty to attend to? The problem is that the religious right is stuck in their single, literalist, paradigm. They have nothing to offer liberals, who aren’t willing to accept the supernaturalist program whole cloth. Evangelism has become about winning assent to supernaturalist claims, instead of being content to convince people to be better people. How odd. Does this mean that the right truly has nothing to offer the left?

A consequence of isolationism is that the “wisdom” of tradition is being locked behind iron walls of dogma. The right is not doing this intentionally. They’re doing it because, again, society has lost the ability to facilitate discourse between reason and faith.

“Liberals”, who are hardly liberal, are no better off. The thrust of modern leftism rejects freedom of speech, for goodness’ sake. Even so, even the old liberals of the West suffer from a fatal conceit. Going back, from Locke through John Stuart Mill, up to the Progressives and New Dealers, the Anglo-American liberal-left has made a god out of Reason. In fact, this conceit is why the Anglo-American conservative tradition has held on so tightly to traditional wisdom. They correctly perceive the harms of making a god of reason, and in rejecting this notion they hold fast to tradition in its place. The problem with making a god out of reason is the question: what is Reason’s will? Yes, logic and science can produce objective conclusions. Taking the word of the technocrats, there might seem to be a will to Reason. Sadly, like God Himself, Reason’s ultimate will is unknowable. People differ in preferences and opinions, about which Reason has nothing to say. Reason makes mistakes, or rather, Reason produces different conclusions based on how broad an inquiry is made. Scientific progress often invalidates the commonly understood scientific truths of the past.

The final question in critiquing liberalism is this: who speaks for Reason, who are its prophets? In a left-liberal society, these people will become the tyrant philosopher-kings. Their dictates about scientific truth will override individual moral thought. Thus, this tradition which values utilitarianism, reason, the absolute power of a unitary Parliament committed to the absolute common good of the entire unitary empire cannot be said to be liberal in the slightest. It is the precursor the same eugenics based scientific organization of society featured in the worst nightmares of George Orwell and Aldous Huxley. The only response the left-liberals have ever offered against this critique is that, “If I personally get the power, I’ll definitely make sure to stop things before they get too crazy.”

Neither liberals nor conservatives, from 1700 to 2020, can completely accept the idea that individuals ought to work upon the evidence themselves and generate moral conclusions with their own individual minds. For liberals and conservatives, either reason or tradition must rule, but certainly not man. Only libertarian politics can accept the premise of individual sovereignty. Only within individuals can faith and reason attain a balance of power.

Democratic Morality

The reluctance on the part of liberals and conservatives to trust the individual is understandable. One of the hard lessons of adulthood for me has been coming to realize how little time most people spending thinking about things. In college I genuinely thought that people who mattered, including a critical mass of middle class voters, were capable of processing difficult political and philosophical ideas. The reason, for example, why I thought America wasn’t libertarian yet was simply because libertarian ideas were new to the public stage. They were new to me, so why not also be new to everyone else? Surely, I thought, after 10 years, people will come over to this point of view. Naturally, this has not happened, and now my point of view about public intelligence has evolved tremendously. I get it, nobody who thinks a lot expects the masses to think very much at all.

I’m a pragmatist. I’m willing to accept the fact that democratic morality is a farce in the sense that no, the common people don’t spend much time thinking about ideas. However, the premise of classical liberalism isn’t that all people always think for themselves. The premise is that thinking for yourself is something that anyone has the potential to do. And no, that does not mean we can all do it well; it means that the fundamental process of life involves the integration of desire, intent, habit, social custom, ideas, evidence, and thought into consistent patterns. This is the process which creates our sense of meaning, no matter who we are. We don’t all get to the same place, but we all travel along the same road getting there.

Libertarianism is the idea that the pursuit of meaning is a right reserved to the individual. No social planner has any higher claim to some insight about life’s meaning than any thoughtless prole. The social planner may perceive a clearer path to the lower’s self-interest, and maybe that guy should listen to Mr. Smarty Pants, but the intellectual has no right to impose their clarity upon anyone else.

This argument was the quintessential argument used against slavery in the Yankee quest to develop an intellectual critique of the practice. Even in the North, racial prejudice abounded. There was a common belief that the mental inferiority of the black race was a scientific fact. Well-meaning Northerners framed their discussion of slavery and abolition, unfortunately, in terms that naively considered that black people might be inferior. The Southern argument that blacks weren’t as well suited for the moral existence pursued by whites was not always refuted by Northerners. However, the Yankees of the Christian Enlightenment still had many powerful arguments against slavery even in light of this prejudiced assumption. Their arguments highlight why democratic morality is correct even when one does not expect the masses to always pursue moral choices.

One particular version of this argument against slavery comes from a prominent preacher of the American Unitarian movement (bolded words highlighted by author).

“Another argument against [holding men as] property is to be found in the Essential Equality of men. I know that this doctrine, so venerable in the eyes of our fathers, has lately been denied. Verbal logicians have told us that men are “born equal,” only in the sense of being equally born. They have asked whether all are equally tall, strong, or beautiful; or whether nature, Procrustes-like, reduces all her children to one standard of intellect and virtue. By such arguments it is attempted to set aside the principle of equality, on which the soundest moralists have reared the structure of social duty; and in these ways the old foundations of despotic power, which our fathers in their simplicity thought they had subverted, are laid again by their sons.

“It is freely granted, that there are innumerable diversities among men; but be it remembered, they are ordained to bind men together, and not to subdue one to the other; ordained to give means and occasions of mutual aid, and to carry forward each and all, so that the good of all is equally intended in this distribution of various gifts. Be it also remembered, that these diversities among men are as nothing in comparison with the attributes in which they agree, and it is this which constitutes their essential equality. All men have the same rational nature, and the same power of conscience, and all are equally made for indefinite improvement of these divine faculties, and for the happiness to be found in their virtuous use. Who, that comprehends these gifts, does not see that the diversities of the race vanish before them? Let it be added, that the natural advantages, which distinguish one man from another, are so bestowed as to counterbalance one another, and bestowed without regard to rank or condition in life. [Pg 19]Whoever surpasses in one endowment is inferior in others. Even genius, the greatest gift, is found in union with strange infirmities, and often places its possessors below ordinary men in the conduct of life. Great learning is often put to shame by the mother-wit and keen good sense of uneducated men. Nature, indeed, pays no heed to birth or condition in bestowing her favors. The noblest spirits sometimes grow up in the obscurest spheres. Thus equal are men; and among these equals, who can substantiate his claim to make others his property, his tools, the mere instruments of his private interest and gratification? Let this claim begin, and where will it stop? If one may assert it, why not all? Among these partakers of the same rational and moral nature, who can make good a right over others, which others may not establish over himself? Does he insist on superior strength of body or mind? Who of us has no superior in one or the other of these endowments: Is it sure that the slave or the slave’s child may not surpass his master in intellectual energy or in moral worth? Has nature conferred distinctions which tell us plainly, who shall be owner? and who be owned? Who of us can unblushingly lift his head and say that God has written “Master” there? or who can show the word “Slave” engraven on his brother’s brow? The equality of nature makes slavery a wrong, Nature’s seal is affixed to no instrument, by which property in a single human being is conveyed.”

-William Ellery Channing, Slavery, 1835

Channing argues that the equality of man is not found in the sameness between us. We are all quite different from one another. Rather, man’s common heritage lies with our shared ability to process ideas and beliefs, and the basic ability to decide and evolve based on them. This is individual moral sovereignty. If earthly authority, traditional or intellectual, finds fault with this basis for equality then there is no equality. In their world might makes right, and might will stamp upon our foreheads either “master” or “slave”.

Neither society, tradition nor intellectualism can supersede and supplant the right of the individual to make moral judgments for his own good and the good of others. Thus, moral sovereignty is not a principle primarily applicable to the common masses. It’s a principle which is meant to constrain the ruling elite from imposing upon those beneath them.

What libertarianism asks of the intellectuals is that they think “as if” their mind is the mind of everyman. Thus, even if they are certain that they know better, they must act “as if” they have an equal burden to persuade others peacefully as would anyone else. This is why libertarianism is different than liberalism and conservatism. Both reason and faith live within the individual. They exit the individual bearing his bias. There is no authoritative scientific truth that did not first come from the limited scope of thought of a finite individual mind. There is no authoritative religious truth that does not ultimately rest upon the assent of the individual in exercising faith towards believing in it. When Unitarians like Channing say the power of moral judgment comes from God, what they mean is that it was not created by man, but rather he came into life already with the ability. The ability to engage in individual moral judgment was created by no man, and so no man is entitled to overturn the right to exercise it.

Only libertarianism is willing stick to the fundamental rights of the individual mind. This is why morality and religion’s realignment with science and the secular must begin from within the libertarian community. Religious authority and intellectual authority do not have the ability to bridge the gap, for they are in competition with each other. Only within the individual mind and soul does reason and belief coexist with equal authority – equal in the sense that the individual possesses a sovereign entitlement to grant to either whichever weight he chooses.

The moral authority of the individual and the judgment of individual reason is the centerpiece of the intellectual and spiritual paradigm which unites the future secular to the future theist. Secular philosophies and religions that cannot accommodate the moral authority of the individual simply cannot endure and exist in harmony in the future society. That is the hard truth I advocate.

Many conservative Christians won’t accept this liberal Christianity. They won’t allow the individual soul to hold greater spiritual authority that the theologian in interpreting the Bible. Although, the Protestant tradition comes closer to accepting this. Nevertheless, there’s no reason why even the Catholic tradition couldn’t admit that assent to the truth of tradition and the authority of the church ultimately rests on individual faith.

The leftists may have even more trouble giving ground. They will struggle to return from the post-modern world which has abolished the constraints of habit and moral duty. It is ironic that the stumbling block of the reason-worshippers might be the binding lusts of the body.

The relative positions of power that both sects of society possess will have to be relinquished to make the change. For this reason, only Libertarianism has any incentive to promote the new paradigm. Only by accruing power to individuals, and away from the liberal and conservative power centers, can Libertarianism succeed in bridging the gap.

The gap can be bridged

What are the first steps that Libertarianism can take to restore a balanced moral discourse? Libertarianism has plenty to say about politics, economics and even ethics. What about morality? The first thing Libertarianism has to say about morality is clear and simple: individuals must be empowered to make moral judgments, over and above any other outside moral authority. What next?

Libertarianism must develop a framework for moral discourse. This is a common language, with commonly understood forms. For example, in Christian Europe everyone knew the stories of the Bible and the basic doctrines of Christianity. Even non-believers could speak in the language of Christian morality. This, as of quite recently, is no longer publicly possible in the West. What is needed is a new language.

If people with different beliefs nevertheless share a common language of moral discourse, then society can begin to act constructively, rather than de-constructively. There must be an education in common forms. This won’t be possible if the forms necessarily alienate one side or the other (for instance by being based on supernatural beliefs that seculars cannot accept). If there’s a common language of moral discourse, then rather than fighting or desperately vying for political power at all costs (with no standards), people can engage in true discussion. Minds can actually change. Where necessary, boundaries can be clearly drawn. Good fences make good neighbors.

Morality is a focus that most people would like to avoid. Morality is personal. It deals with beliefs. If an exercise of moral authority is extended past the individual mind, then it quickly becomes tyrannical. It’s only natural that most people would mistrust morality. Perhaps we’d prefer not to have to deal with it. Anything goes? This is an unsatisfactory answer, and it only lasts until the good times end.

Morality isn’t just that set of things you’re not supposed to do. Morality is a tool for understanding our purpose – as individuals and society – and the level of progress we are making towards that purpose. Civilized society needs such a tool, just as we need law, science, and art. The present lack of a functional and coherent moral discourse is the single source of Western Civilization’s decline. Presently, the West tends to steal concepts from the past and apply moral language expediently to serve political prerogatives. Not only does this language lack its former context, and therefore meaning, it’s also becoming less and less culturally relevant – soon politicians may not invoke it at all anymore.

Civilization needs a coherent moral framework. The way we avoid tyranny is by establishing the moral sovereignty of the individual first, as the basis of the entire framework. Only Libertarianism can do this. Fortunately, there’s an abundance of material which can help.

In 19th century America, Yankee liberals were both committed Christians, and enthusiastic practitioners of the enlightenment commitment to science and reason. Many of them were Unitarians of the Christian Enlightenment tradition, and the philosophy of the Scottish Enlightenment’s Common Sense school was required learning at Harvard University. They developed an entire curriculum concerning moral living. This framework not only offered moral prescriptions, processes of moral judgment and libertarian political conclusions, but it also served as a practical guide for personal self-improvement. These old textbooks still exist. Digging them up and learning their basic frameworks would be a fantastic starting point in developing a contemporary libertarian moral science.

The absolute centerpiece of 19th century Yankee moral science is the adoration of the human conscience. The conscience is upheld as a supernatural power given to man by God. It is the central actor in human morality, and the entire moral science revolves around the practical exercise and development of the conscience. This is profoundly relevant to libertarian philosophy. The conscience is the individual moral will and moral consciousness. It is the prime mover within the individual which leads directly to human action. There is no better spiritual expression of libertarian thought then the doctrine of the conscience in Christian Enlightenment thinking.

The supernatural and religious nature of the conscience was also behind the fall of Yankee moral philosophy. As science progressed, more and more Yankee intellectuals began to realize that the idea of a supernatural conscience was folly. Since the conscience was central to this moral philosophy, as it fell, so did the entire scholarship of Yankee morality. This is why we don’t learn morality in American academic institutions anymore. Like Earth-centric models of the universe, the supernatural conscience was discredited by science. There are reams of scholarly work explaining the motion of the planets if we assume the Earth is at the center of the universe, but these works are now held to be irrelevant. Likewise, the old American moral science simply lies abandoned.

Once upon a time, American university professors were almost exclusively laissez-faire in their outlook on economic policy. In politics, they were staunch defenders of limited government. They were, essentially, libertarian. In my opinion, because the supernatural conscience was discredited, Yankee moral philosophy was also discredited. Without a coherent moral philosophy to defend the ideals of liberty, Yankee intellectuals abandoned it. By the turn of the 20th century, these institutional defenders of laissez-faire more or less converted to become Progressives and New Dealers. A few others embraced what would become Christian Fundamentalism (started at Princeton University). The libertarian strain gave up and joined the liberal or conservative camps. World War II represented the final political victory of the united conservative and liberal strains of Anglo-American thought against the last bastion of the libertarians (the people).

Contemporary libertarians understand the value of the old ideals of liberty. It therefore behooves libertarians to resurrect the old proto-libertarian moral philosophy, and to begin to redevelop a coherent moral language for our society. This task is much easier than it sounds. Much of the work has already been done. Reams of scholarship from the 19th century Yankee liberal Christians already exists. All that is needed is to recover the lost keystone – the conscience – and reframe it in secular terms. If the centerpiece – the conscience – can be recovered, so can most of the resultant moral science.

Recovering the conscience

The concept of the conscience can be recovered. Clearly, the Christian Enlightenment philosophers were perceiving something real in their adoration of this moral feature. This is evidence of something substantial, whether it is supernatural or not. Yet, is conscience a reliable concept at all? Post-modernists would say conscience is the just subconscious shame experienced from social indoctrination. Sure, indoctrination affects shame, but conscience is not all about shame.

Take the example of Japan. It is a thoroughly non-ideological society, but the amount of social shame is astronomical. This doesn’t stop people, when they’re privately in their own bedrooms, from doing things there with almost no sense of guilt. It’s the utter repudiation of post-modernism. Social shame exists, but ideas aren’t part of it. When it comes to moral ideas, they can’t be reduced to mere social constructs. There’s more going on, since social constructs can exist free of ideas.

The word conscience has an interesting history. Its etymology shows that its literal meaning is: “inner thoughts” or “inner knowledge”. Considering again Japan, there’s no reason for a human’s inner thoughts – taken literally – to have a thing to do with moral righteousness. How then did the West attach to conscience the concept of moral rectitude? Maybe the West believes – going back to pre-Christian traditions – that right and wrong are self-evident. Implicit in our most ancient cultural beliefs is the idea that evil and wrong are acts that must be committed knowingly, because ignorance of good and evil is impossible.

If you are from the West you would understand the basic meaning of conscience. Isn’t it a remarkable concept? How is it that we would take for granted something so profound: that there is not only right and wrong, but that it is fundamental to human nature to know the difference. Libertarian circles will be familiar with the critiques of natural law theory. Human nature is ill-defined. Yet, in the Christian Enlightenment there is a very aggressive application of human nature based natural law outcomes into political theory. If humans absolutely know right from wrong, then of course there is a basis for natural law.

When detached from its supernatural definition, conscience loses its power as a definitive proof of moral principles (for example, that humans definitely know right from wrong). However, conscience does not loose its usefulness as a framework. Conscience is a universal sensory power that correlates ideas and perceptual information to actions, norms and even law. Even if we don’t know right and wrong exactly, we have this great filter or funnel; conscience is like a spiritual CPU. In this light conscience truly is the heart of libertarianism and the strength of the West. Our conscience, our inner thoughts: it doesn’t necessarily know right from wrong – but it is able to conceive of right and wrong if asked to do so, and it can use these categories to frame everything else related to self and society in a context of right and wrong. That is, the conscience is no more nor less than what I originally described as the essence of classical liberalism.

Conscience is moral judgment being exercised within the individual mind; it’s the categorization of information, feelings and ideas into consistent groups that can be communicated to others irrespective of personal bias.

If humans aren’t perfect “moral knowers”, maybe we can still say they are excellent “moral computers”. This is the source behind libertarian views about what’s axiomatic, about human action and argumentation ethics. The moral engine is the constant. It is the (abstract) machine that we humans use to take actions, make decisions, perceive the world, seek meaning, and also argue with each other. If we want to do philosophy or spirituality right, the first step is to understand ourselves. We have to define all our frameworks in terms of the engine of human action: the conscience. In so doing our secular and religious pursuits have a common language of discourse.

If we treat the conscience this way, we can now return to the 19th century texts which discuss conscience as central to morality. That is, the moral lessons of these Christian Enlightenment textbooks can be understood by thinking of conscience and duty the way libertarians think of human action, argumentation ethics, and so forth. If we choose to pursue certain ends, then we must also choose to accept constraints derived from choosing to value those ends. This is the justification for creating a model of the conscience, and in turn a moral philosophy surrounding it.

A model of the conscience

In the 19th century moral discourses and texts, a number of common features are discussed. Words such as “habit”, “self-culture”, “moral taste”, and so forth, appear as commonly as the word “conscience”. Almost all of these, like conscience, represent important cornerstones of the moral framework used by liberty-minded Yankees of the era. They are also all more or less attributed to God as supernatural features put into man deliberately according to the will of the Creator. If conscience is to be expressed in secular terms, a coherent model of the conscience must also make room for these other concepts. So long as these concepts all share a coherent secular definition, and can be practically used in making moral judgments, then the 19th century moral science can be recovered.

As a first step in re-interpreting the old moral science, I have created a simple model of the self which is framed in terms of secular philosophy. I will now present the model in order to kick off a discussion which I hope will cause the libertarian community to reconsider the moral teachings of America’s past. I am presenting this model for two reasons. First, I would like to discuss and review some of the old moral textbooks in future essays. Second, the model itself represents a basic solution to the core question presented in this essay. How can reason and belief be balanced? Why must this occur within the individual?

Philosophers like to discuss the is-ought dichotomy, which says that logic cannot tell us what we ought to do (morally). Logic can only tell us what to do after we have selected our preferred values (belief). The universe (and therefore science) are more or less silent, or apathetic, about human purpose and the meaning of life.

“Is-ought” is philosophical proof of our right to exercise moral agency. No intellectual authority can prescribe authoritative meaning or purpose for other humans. They can only persuade our individual senses. As I said before, if libertarian principles reign, then both scientific and religious authorities must submit to the moral sovereignty of individuals. In so doing, there can be harmony between them.

The work of balancing “is” and “ought”, reason and spirituality, was started long ago. Thomas Reid, of the Scottish Common Sense school, addressed the issue. He even forwarded his work in the mail to David Hume himself, the modern progenitor of the is-ought complaint. Although Reid, an aforementioned father for the Christian Enlightenment, invoked God a lot in his philosophy, he still presents a framework that balances idea and sense. Prior to Reid and Hume, John Locke proposed the real existence of ideas as a framework for philosophical truth. Reid agreed with Hume’s critique of Locke that ideas cannot be proven to have a real existence outside of the mind. However, unlike Hume, Reid argued that thought is still valid. He points out how sense and perception are sorted by the mind into meaningful categories which provide distinction and a basis for sound judgment. Reid’s model closely conforms to many network descriptions that come into play in complexity studies, linguistics, and even machine learning. These latter fields are hardly religious, so a framework for balancing is and ought can exist in completely secular terms.

Defining conscience in secular terms requires a model of the self that respects the implications of the is-ought problem. It should not try to answer any ultimate questions. It should only create categories which are useful for analyzing phenomena that may or may not have explanation. The phenomena pertain to the self, which has material and possibly spiritual existence. Much about the self goes unexplained by either science or religion. The categories must capture known and unknown alike, and provide a consistent basis of understanding, and therefore communication, between belief and reason.

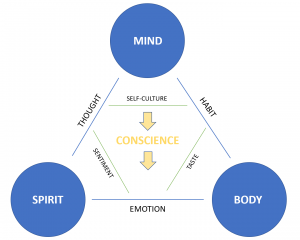

This this the model which I have developed to describe the self (the morally sovereign individual) according to categories which fulfill the purposes mentioned above:

The first part of the model proposes that there are three elements of the human person: body, spirit, and mind. These are not literal elements. They are not discrete, platonic forms. They are categories. They are defined only in relation to each other as abstractions. That is, features of human life that are neither of spirit or of mind, must be of body. Body, therefore, does not mean literally the human physical, material form. The nature of the real substance correlated to these categories is left to individual interpretation.

The categories represent a philosophical triad. Known, unknown and understanding. Past, future and present. Analytic, contingent and integration. Thesis, antithesis and synthesis. Whatever the “human person” is, we are viewing it through these divergent lenses. The triad is one of the most basic tools of philosophy.

These elements can also be described using the words Logos, Praxis, and Impetus. When we use the mundane word of each element, we are approximating the literal thing (although only the body, strictly speaking, has literal form). When we use the categorical word, we are approximating the result of the action by the literal thing.

Logos (Mind) is past-facing. It is the hard, fast, clear-cut and absolute. It orders the other two elements, providing an unimpeachable context.

Praxis (Body) is present-facing. It is action, and the transition between states; including the means of transition.

Impetus (Spirit) is future-facing. It is the preferred, ideal self of forms and dreams calling back, willing itself into reality. It is the most esoteric element.

Each element is connected, or rather, they overlap to create categories which are best described as the fundamental aspects of self. They are Spirit + Mind = Thought. Mind + Body = Habit. Body + Spirit = Emotion.

Thought is the parent of philosophy and science. It is also awareness since it is apart from Body (being Spirit+Mind), seeing “self” as a creature which inhabits the separate “body”.

Habit is a highly neglected element of self, in contemporary amorality. This includes a comfort with the unseen because of taking the unknown for granted as an unchanging whole. It’s how we see our own self-evolution, our aspiring soul unchanged, but our mind and body improved. It’s who we are, free of moral judgment. We are judged based on our intention, and ability to change. We are not just simply on how we are (though we are accountable for our past management of our habits).

Emotion is the sensory percepts of the body combined with a wider context of expectations. We manage our state transitions, define and record them, according to emotion. Emotions are the milestones in or memory, marking changing conceptions of self.

The aspects of self combine to form another set of categories. These are the regulatory elements that govern the dynamic self.

Emotion and Thought create Sentiment, which is the heart of religion, mysticism and the quest for meaning. Sentiment is a lens to interpret emotion and sort memories. Sentiment can also be projected or invoked to recall memories. Sentiment is how we construct literature that recontextualizes our beliefs. It is a spiritual medium, so it revolves around intention and aspiration; it is future focused. It asks, what will I do, now that I feel this way? Or, what does it mean to feel this way?

Thought and Habit create Self-culture (like agriculture) which is another word for self-improvement. This is reason focused and orders the emotional and physical into structures.

Habit and Emotion create Taste. Taste is the parent of art. It is ill-defined, because of subjectivity, but it represents the manifestation of the heights to which we reach. When satisfied, it is meant to be attended naturally by feelings of euphoria, contentment, and so forth. It is the manifestation, in the present, of the spiritual flow. It’s like a spiritual hash function.

At the center of all this is the Conscience. Simply put, the conscience is the CPU. Its role is to cause everything to be correlated; it keeps things consistent. It connects all the parts to each other and creates harmony; it defines single categories by their relationships to all the others. Emotion, logic, desire, hope, the future, the now, pain, happiness, other people, the self, history, memory, anger, joy, effort, all relate together to create a common picture. This is the ultimate self. Its powers are the combined regulatory elements, its consciousness perceives the combined aspects of self. It operates in past, present and future

If we take the essential two points of classical liberalism for granted, then we say the individual mind is the moral judge, the moral actor. With this model, the conscience is that engine which takes all the parts I mentioned and perceives a common thrust. Your “inner thoughts” are aware of all of the pieces and present to you the balance that you cannot deny, because it is a factual reality of which you are aware.

In this sense, the conscience is not merely a black box. It is something we can try to understand more deliberately by consciously separating out our aspects of self into their respective categories and weighing our thoughts and feelings concerning each aspect more carefully.

We can extend this process of self-awareness outward to others and arrive at moral and ethical conclusions. We can arrive a legal or even economic conclusions. We have a means of knowing when we should say no. We have a way to judge when pain in the present is necessary for gains in the future. In the end, we have also begun to create a common language of discourse between religion and the secular.

In the history of philosophy, some have dethroned logic, and some have exalted it. Imagine a view of logic sitting upon its throne, but within the boundaries of its natural kingdom. There is a balance of power between it and its neighbors: spirit and body. Yes, it sounds like a forced metaphor, and yet, this balance is why American liberty worked so well. When the balance of power was disrupted, that’s why liberty stopped working.

Now we also give spirit its own kingdom. The religious, the neo-religious and even the atheistic can all speculate and live in the spiritual kingdom of their choosing. The hedonists too – those eternally oppressed by the constraints of traditional religion or ideology – have their kingdom of the body as well. The core concept is that these three elements: mind, body, and spirit, though not really separate, still have a place in their own kingdoms. Good fences make good neighbors.

The kingdoms play off of each other. The secularists might lay claim to territory in the kingdom of the mind, but the religious can assert their rights in the kingdom of the spirit. Likewise, pseudo-spiritual beliefs of the left can be accurately called-out as non-rational by the right, even if the left doesn’t admit to be operating under a religious framework. Battles of the mind will be fought in the kingdom of the mind, and battles of spirit left for that kingdom. Understanding these categories, as a common framework for discourse, is like lifting the fog of the culture war.

Society’s problems of the body, such as addiction, can be conceived of apart from spiritual and moral prescriptions. Is addiction a moral problem? No. Is aspiring for a better life, but not being willing to admit to addiction or not doing anything about it a moral problem? Yes. Here the person refuses to harmonize the spirit with the body, it’s a failure to heed the conscience. Either the addiction must be fought, or the aspiration must be given up. That is the moral conclusion.

The problem now is that our moral discourse is a mess. We can’t agree on facts, first of all. Second of all, our aspirations and beliefs vary wildly but we don’t even talk about them. Many people don’t even know what they believe. If you’re arguing with someone who doesn’t even know what they believe, that’s the first thing to focus on. We also have different situations, different backgrounds, different abilities and different points of view. We have to sort this mess out, and that’s not possible unless there’s a common language for discussing these things. Now we have a starting point to develop such a discourse.

Towards morality once again

The key to reinterpreting the old American moral texts was recovering a meaningful framework for conscience. In my opinion, I have provided a decent starting point in this effort. The literature of the Christian Enlightenment, the Yankee and Unitarian moral philosophy, is relevant to Libertarianism today.

A famous Unitarian preacher named William Ellery Channing, quoted above, provided a moral and philosophical argument against slavery. This text not only invokes a version of the non-aggression principle long before it was so called, it also presents a stark defense of individual moral sovereignty. It’s a text which is relevant to libertarians today. There are countless texts from this era and intellectual movement which have things to say to libertarians today.

This essay has mentioned a 19th century high school morality textbook. The very first section of this book discusses human intent and human action as the starting point for considering moral questions. This sounds an awful lot like Misesian philosophy. Why is this?

The liberal Christians of the American Christian Enlightenment, by 1830, had coalesced under the label “Unitarian”. Using this label, we can review the personalities who would have been influenced by these ideas. Among them, John Adams and Thomas Jefferson (who boldly proclaimed that Unitarianism would be the future religion of American civilization). William Lloyd Garrison, the abolitionist, was Unitarian. The famous proto-libertarian Lysander Spooner also affiliated with the Unitarian movement.

Unitarianism was the last expression of the Christian Enlightenment in America. The philosophy of the Christian Enlightenment was explicitly borrowed from the Scottish Enlightenment. The Scottish Enlightenment is directly connected by many to the philosophy of the French liberals. These are the same people who inspired Bastiat and Mises, ultimately. Not only are the ideas of 18th and 19th century American liberty strongly correlated to continental liberalism and modern Libertarianism, they are probably genealogically related. Unfortunately, much is said of the influence of Adam Smith and David Hume on the French liberals. Little is said of Thomas Reid, who’s influence in 18th century America was stupendous. Hayek might mention Smith and Hume, but if you search for “Thomas Reid Common Sense” and “French Liberal Philosophers”, you’d see that the influence of Reid on Classical Liberalism was hardly insignificant. In continental philosophy, just like in America, Reid’s Common Sense school – particularly its moral elements – was probably abandoned because of its strong religious overtones.

In my opinion, America’s founding philosophy – maybe also even the most important elements of Classical Liberalism – is grounded in Reid and Common Sense above all else (Locke, Montesquieu, etc.). The conscience is the moral lynchpin of a truly libertarian moral philosophy. It identifies the power that makes the individual the moral sovereign in society. The relative authority of reason and belief are settled in the individual mind. This is the core principle of Classical Liberalism/Libertarianism. This widely influential and relevant school of thought has been almost neglected by history. The cause is likely the school’s desire to harmonize reason and belief, an effort which has been completely abandoned.

This essay has demonstrated that a secular reinterpretation of Christian Enlightenment moral philosophy is possible. Libertarians should begin to review the literature of this school and develop a modern libertarian moral philosophy. Secular society has discarded religion without replacing it. The religious increasingly isolate themselves and entrench in tradition. Western Civilization has lost its anchor and is dying. Libertarians can fix this by championing individual moral sovereignty. First, we need a common language of moral discourse. We need a coherent moral philosophy.