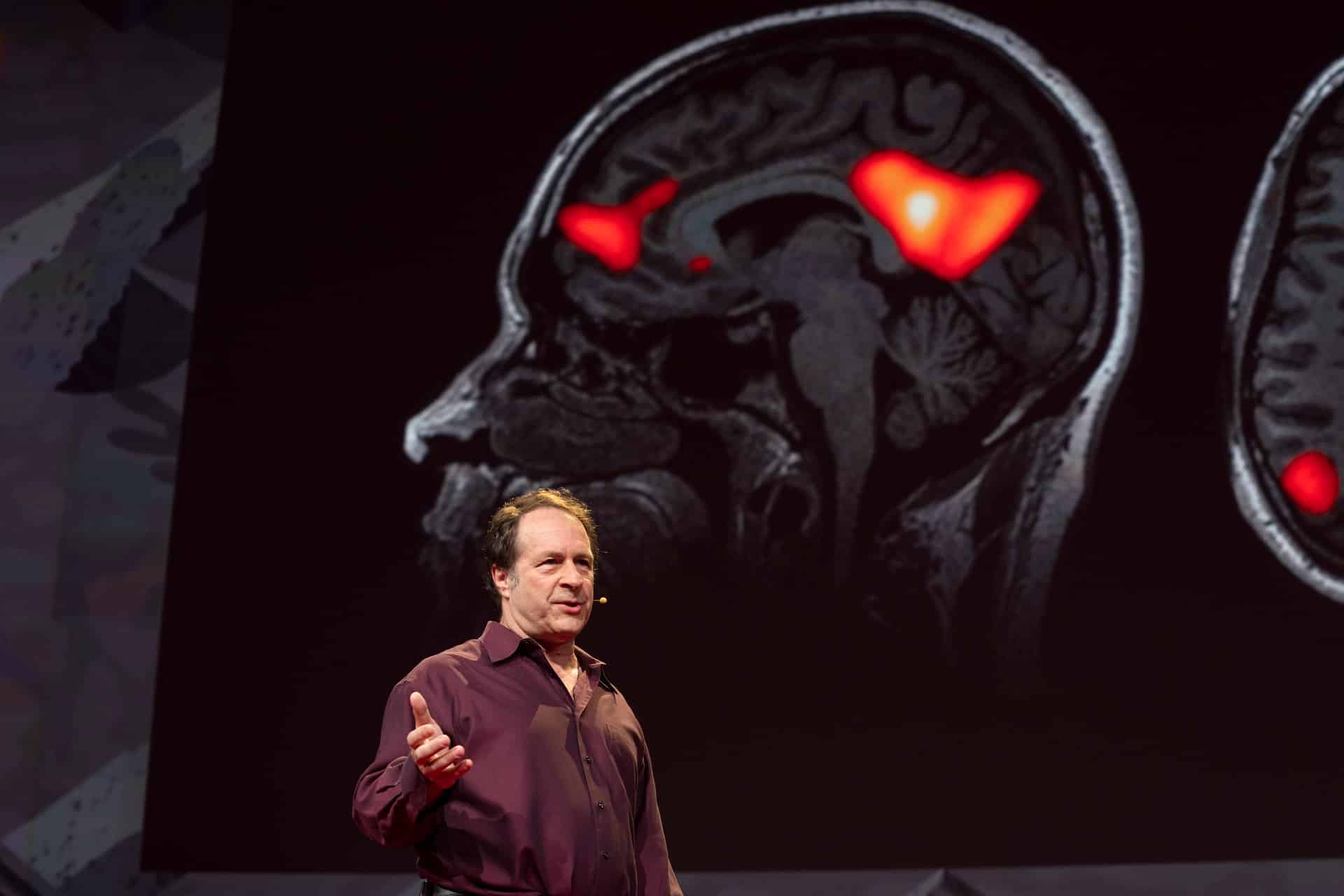

In early 2024, Rick Doblin—the man whose work launched one of the biggest social and cultural movements of our time, “the Psychedelic Renaissance”—was expecting to see the crowning achievement of his life’s mission. The non-profit he led and founded, the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS), had recently published the second of its Phase 3 clinical trials of the psychedelic drug MDMA, investigating its efficacy in the treatment of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). The results seemed incontestable.

The MDMA-assisted therapy developed by Doblin and his team was shown to produce drastic improvement in 72% of patients with PTSD, so that two months after treatment, they no longer met the criteria for the disorder. This made it far and away the most effective treatment available for what is an otherwise largely intractable, debilitating, and potentially fatal mental illness, which afflicts over thirteen million Americans. And this second trial was the last hurdle to be cleared before the drug could receive FDA-approval and become a legal, prescription medication. The FDA-approval of MDMA was the main target Doblin set out to achieve when he founded MAPS four decades earlier.

I interviewed Doblin for the Libertarian Institute ahead of the FDA decision that summer, fascinated by his radical approach of working within the framework of a corrupt legal system in order to change the system. In doing so, Doblin endured decades of insane injustices at the hands of the government, which would’ve likely led anyone else to give up in outrage and despair. Yet he remained single-mindedly focused on his life’s work, through which he transformed the whole legal landscape around psychedelics. His labor tore open the gates for a new wave of cutting-edge research, therapy, and popular enthusiasm for psychedelic drugs such as ibogaine, psilocybin, ayahuasca, and LSD, which hundreds of studies are currently showing to be immensely effective for treating a wide variety of mental health conditions.

When Doblin was eighteen-years old, in 1972, his own experience with psychedelics, he said, “brought me a life’s mission,” to “devote myself to psychedelic research and psychedelic therapy,” the healing potential of which he experienced firsthand. This was, however, one year after the U.S. government under Richard Nixon launched the “War on Drugs,” banning these substances for all recreational, research, and medical uses. Blocked on his path to becoming a psychedelic therapist and researcher in any lawful capacity, Doblin’s mission became “to remove the obstacles” that had obstructed him. He went on to earn his PhD from the Harvard Kennedy School of Government and calls the legal work he now does “psychotherapy for sick public policies.”

Doblin launched MAPS in 1986, with the stated mission of creating “a world where psychedelics…are safely and legally available for beneficial uses, and where research is governed by rigorous scientific evaluation of their risks and benefits.” But the company’s first five proposals for psychedelic research were summarily rejected by the FDA, until Doblin at last succeeded in wresting the FDA’s permission for a Phase 1 study with MDMA in 1992. After that study had clearly demonstrated that MDMA was safe for human consumption, Doblin spent six more years fighting the FDA bureaucracy to procure the permission for MAPS to conduct a Phase 2 study of MDMA-assisted therapy in 2001. After six Phase 2 studies in sixteen years, showing his MDMA-assisted therapy to be highly effective in the treatment of PTSD, Doblin invested eight months in 2017 undergoing a “Special Protocol Assessment” to reach an agreement with the FDA on the research design for his Phase 3 studies.

The upshot of this was a written “Agreement Letter,” Doblin explained, in which the FDA stated that it had agreed to MAPS’ research design and made a commitment “to approve MDMA-assisted psychotherapy for PTSD if [the] design generates statistically significant results.” That the design did. By 2024, two Phase 3 studies published in Nature demonstrated the unprecedented efficacy of MDMA-assisted psychotherapy for PTSD, with a statistical significance of 1-in-10,000 for the first study and 1-in-2,500 for the second. When “you multiply them together,” said Doblin, “it’s one in twenty-five million that two of these studies” produced those results by random chance.

In preparation for the impending legalization, MAPS raised upward of $100 million for its for-profit pharmaceutical arm, Lykos Therapeutics, to be ready to roll out and commercialize MDMA-assisted therapy once it received FDA approval. And then, in August 2024, “the FDA decision was worse than any of us [had] anticipated,” said Doblin. It outright rejected the New Drug Application for MDMA, demanding that MAPS conduct a third Phase 3 study to gather more information, a process that would require at least three more years.

What happened, Doblin explained in a postmortem, “is that the people at the FDA that we made [those] agreements with [seven years ago] had left the FDA” and were replaced by new, “more conservative” ones. “The cost of this bureaucratic backpedaling,” he wrote in an official statement, “is not abstract. Thirteen million Americans live with PTSD today. Every year of delay means more will die by suicide and more remain trapped in cycles of trauma and despair…The science is clear, the urgency is undeniable, and the human suffering is immense.”

I interviewed Doblin again after the FDA decision, wanting to get his thoughts on what could be learned from this defeat. It would seem, after all, that Doblin’s approach of working within the system in order to change it had fetched up in a dead end. And that would seem to bear out the libertarian argument that regulatory agencies like the FDA are a corruption of the government’s proper functions and any attempt to cooperate with them is likewise improper and self-defeating. Yet Doblin doesn’t see it that way.

This defeat, Doblin said, “was not the result of cooperating with the FDA”—up to that point, his approach “was working.” Nor does he cast all the blame on the FDA system for betraying agreements and rationality. After all, his iconic approach of working within the system to change the system had never been one of trust in an honest and rational government. His was, from the start, a program of persistent subversion of the political status quo. And he takes much of the blame on himself and his team for straying away from the principles that led them to success in the first place.

“The main mistake that we made,” Doblin said, “was going from startup to Big Pharma too soon”—and in that process abandoning the politically crucial campaign to educate the public about their new therapy.

With the FDA decision approaching, advisors told Doblin he had to “raise $80 million to prepare for commercialization” and be in position to quickly deliver the therapy to millions of people who needed it. “But I was unable to raise [those] mega millions” from philanthropy alone, Doblin said. So he raised it instead from investors, in exchange for a controlling stake in MAPS for-profit arm, Lykos.

The investors soon brought in “all these traditional pharma people,” said Doblin, who mistakenly “thought that we’d reached a point where the only thing that mattered was the data,” and then promptly “dismantled all the things I had done to build cultural support as well as get the data.” Assuming the science to be undeniable, and that “this was now a rational process,” they adopted “a quiet period,” which is “what Pharma companies [typically] do when they’re developing a drug.” They therefore “decided not to respond to critics, not to respond to the media,” and to shut down all the MDMA research MAPS was conducting “in seven countries in Europe,” to focus their limited resources exclusively on FDA approval.

“We even had a Rick Rules Committee,” said Doblin, “to control everything I said” during that quiet period. They feared, for example, that Doblin’s open “endorsement of ending the drug war will alienate the FDA or DEA or somebody,” which was “100% wrong, because of [my strategy] of having been honest with people the whole time. The FDA has known from the very beginning, as has the DEA, that I believe that we need [systemic] drug policy reform,” and they’ve “never really held it against me.”

Ultimately, the FDA justified its rejection by citing a body of unchallenged criticism, in the media and scientific journals, during that quiet period. And the major party at fault, Doblin said, were not the dishonest critics, but his own side for neglecting to honestly answer them. “The main message is that if you’re going to be an innovator…you have a constant challenge to educate people about what” you’re doing. “Science is downstream of culture. And when you stop paying attention to culture and you just think the science is the only thing that matters, you’re in big trouble.”

“I wish I would have had more confidence in myself, actually,” said Doblin, to continue operating “in startup mode and learn about commercializing a drug on the job with a small team,” instead of relying on these pharma “experts” in commercialization, who merely applied their “traditional approaches” to a thoroughly “non-traditional, innovative thing.” Doblin has since resigned from the Lykos board of directors and is again doing through MAPS, the non-profit, “all the things I thought [Lykos] would do [but] which they have now divorced themselves from.”

The FDA rejection was certainly “heartbreaking,” confessed Doblin, and it was important to give himself “that time to mourn and to just let the sadness sink in.” But “what I realized, after a month or two, that changed my mood pretty much entirely,” is that the fruits of his labor reached far beyond this immediate FDA decision. While making MDMA a legal medicine was his direct purpose for the last forty years, in the course of pursuing it, his work indirectly “opened [the] doors for others to conduct their own promising research” with psychedelics.

“Even if MAPS and Lykos both would disappear,” Doblin said, “the psychedelic ecosystem” has already “been launched”—and is “moving forward [in] a wave that I think is unstoppable.” Over half-a-dozen psychedelic drugs are on their own tracks to FDA approval, patients are getting much-needed treatment in hundreds of studies all over the globe, and Colorado, Oregon, and New Mexico have already decriminalized plant-based psychedelics.

Doblin does think that Lykos (now renamed Resilient) “will eventually succeed,” and “MDMA will eventually become a medicine,” however long that ultimately takes. He stresses the value of setting “multi-generational goals,” goals that link you with a purpose beyond yourself and your limited lifespan. “If your goals can be accomplished in your own lifetime, they’re too small.”

“Think big. Think multi-generational. Be passionate, be patient, and be persistent,” Doblin concluded his opening speech at the MAPS 2025 Psychedelic Science conference in Colorado. “We are still in the midst of the Psychedelic ‘20s.”