Today [December 15] is “Bill of Rights Day”—commemorating ratification on December 15, 1791.

But what the government-run schools—and supporters of the monster state—“teach” about the Bill of Rights has almost nothing to do with the foundational principles which motivated the people who supported—and demanded it.

They want us to focus on inane trivia—and they definitely present things as if the Bill of Rights “granted” our rights, or were meant to create a nationwide liberty enforcement squad in the federal government.

No, it wasvyou guessed it—about the principles behind what was ratified as the 10th Amendment. Drawing a line in the sand, as Samuel Adams put it, “between the federal Powers vested in Congress, and the sovereign Authority belonging to the several States.”

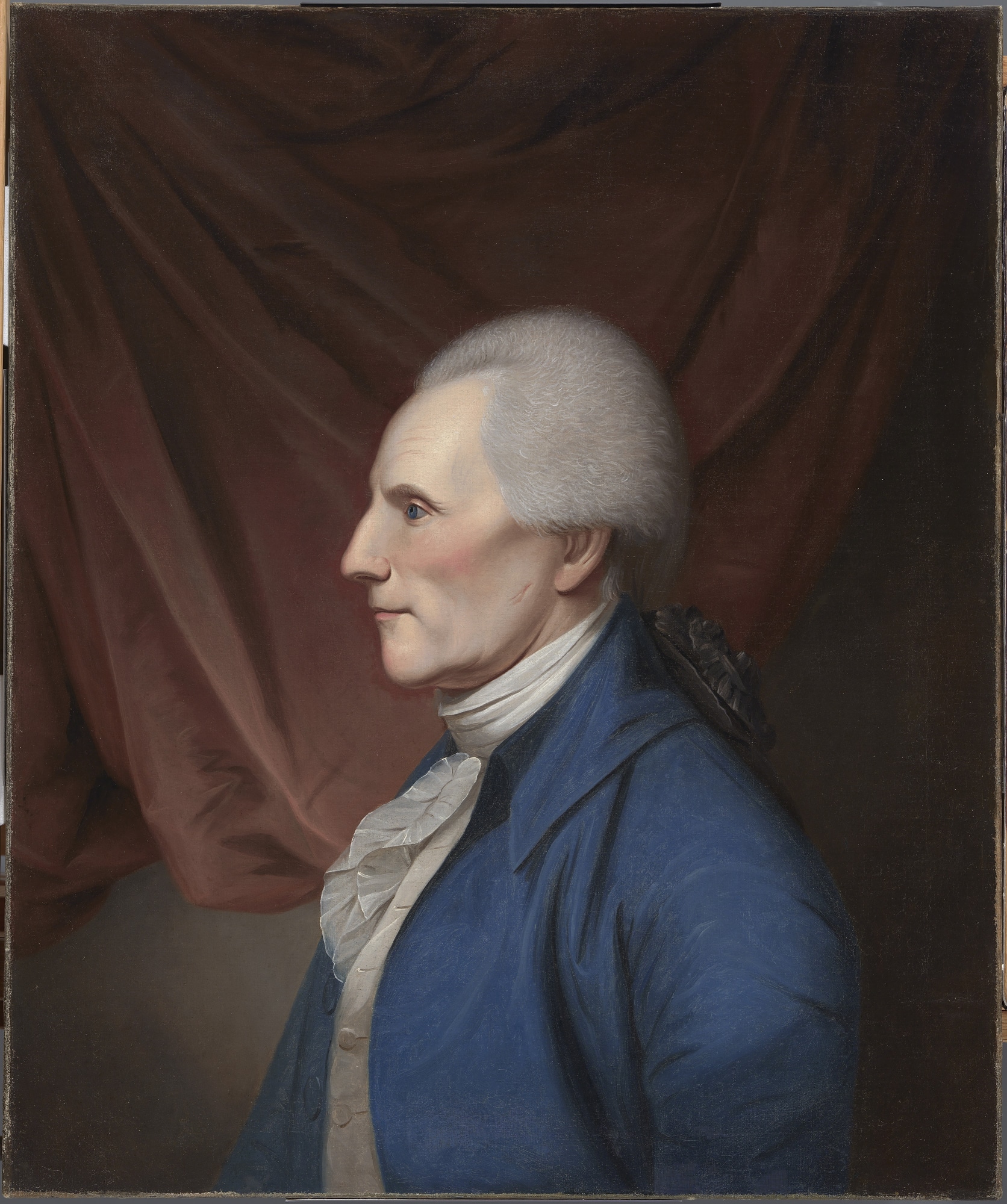

Richard Henry Lee—who on September 27, 1787 in the Confederation Congress proposed adding a Bill of Rights to the Constitution drafted by the Philadelphia Convention—before sending it to the states for ratification, agreed. He said that drawing that clear line between expressly delegated power—and those reserved is “the great use of a bill of rights.”

The same thing happened in a number of state ratification documents, starting with Massachusetts, then South Carolina, New Hampshire, Virginia—and New York.

In early 1788, ratification of the Constitution was almost certain to fail in Massachusetts—home of Samuel and John Adams, Theophilus Parsons, John Hancock—and so many others. A loss there—Federalists understood—would send them reeling in states where it was expected to be a very close call at best—like New York and Virginia. In other words, the entire proposal was close to being doomed.

But – as advised by Richard Henry Lee months earlier, Samuel Adams and John Hancock went along with a plan to ratify, but only with the option of including recommended amendments as well. On February 6, 1788—they did just that, and the very first recommended amendment from the Sons of Liberty will probably look familiar to any reader of the Tenth Amendment Center:

First. That it be explicitly declared, that all powers not expressly delegated by the aforesaid Constitution are reserved to the several states, to be by them exercised.

South Carolina followed their lead with this:

This Convention doth also declare that no Section or paragraph of the said Constitution warrants a Construction that the states do not retain every power not expressly relinquished by them and vested in the General Government of the Union.

And on June 21, 1788—New Hampshire sealed the deal on ratification by also including as their first recommended amendment the same precursor to the 10th Amendment from Massachusetts.

But even after New York and Virginia followed with similar proposals, Federalists in the First Congress stonewalled—and did everything they could to prevent amendments from being considered and sent to the states for ratification.

Samuel Adams, however, didn’t let up—pushing friends like Elbridge Gerry and Richard Henry Lee to get the Bill of Rights done. To Adams, adding these amendments was solely about having “a Line drawn as clearly as may be, between the federal Powers vested in Congress and the distinct Sovereignty of the several States.”

James Madison—who was initially opposed to including a Bill of Rights—and even voted against Richard Henry Lee’s proposal in the Confederation Congress, slowly came on board—maybe for just political strategy. But his dogged persistence pushed it through the congress.

With that history in mind, it makes even more sense why Thomas Jefferson, on February 15, 1791—ten months to the day before ratification—made this essential point about the structure of the constitution:

I consider the foundation of the Constitution as laid on this ground: That ” all powers not delegated to the United States, by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States or to the people.”

Why don’t they teach this history? We can only guess, but I personally think it has plenty to do with the fact that the bill of rights wasn’t about granting rights to people—or having a central government to protect us—but instead—it was about opposition to centralized power.

This article was originally featured at the Tenth Amendment Center and is republished with permission.