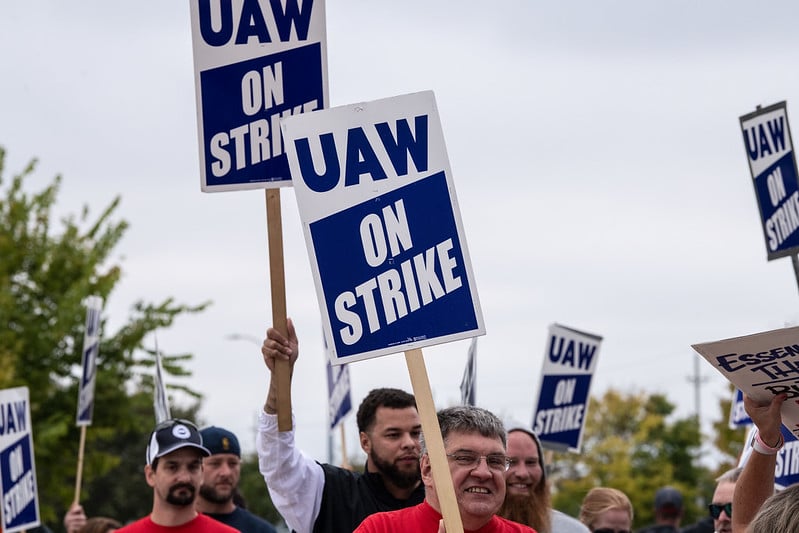

On Friday, September 15, 12,700 members of the United Auto Workers union (UAW) walked off the job at plants owned by the “Big Three” automakers—Ford, General Motors, and Stellantis (which owns Chrysler, Jeep, and Ram). The walkout marked the beginning of a series of long-expected targeted strikes aiming to give the UAW leverage as it renegotiates contracts with the three companies.

The strike is grounded in frustrations over worker compensation. Union members and their supporters point to high profits and CEO pay at the Big Three and compare them to stagnant wages and rising costs of living among autoworkers. They feel like they’re being ripped off.

And they’re right. Like the rest of the working class, autoworkers are being ripped off. Decades of interventionism have built an economic system that harms workers while helping the corporate and political classes. The first reason for this is monetary policy. Ever since President Richard Nixon abolished the gold standard in the early 1970s, a handful of bureaucrats at the Federal Reserve have been charged with determining the value of our currency. And those bureaucrats have decided that the dollar should lose value every year. They aim for a decline of 2 percent annually, but the rate has been higher in recent years.

Dollar devaluation is a political choice. And it hurts workers. In an unhampered market, money becomes more valuable as societies grow wealthier. Goods become better and more affordable. And money saved grows in value.

Under our current inflationist fiat regime, the opposite happens. Savings shrink in value by design. The result is spelled out by Saifedean Ammous in his book The Fiat Standard:

The culture of conspicuous mass consumption that pervades our planet today cannot be understood except through the distorted incentives fiat creates around consumption. With the money constantly losing its value, deferring consumption and saving will likely have a negative expected value. Finding the right investments is difficult, requires active management and supervision, and entails risk. The path of least resistance, the path permeating the entire culture of fiat society, is to consume all your income, living paycheck to paycheck.

We can see, then, how monetary policy leads to mass consumption, low savings, and hyperfinancialization—all at the same time. In fact, one of the most notable examples of the financialization of the economy since the 1970s has been the growth of the Big Three automakers’ financial arms—GM Financial, Ford Credit, and Stellantis Financial Services.

In fact, as Ryan McMaken highlights: “By the early 2000s, a majority of GM’s profits were coming from its financial operations and not from automobile production.”

In other words, the automakers have profited from the very same government policies that devalue their workers’ paychecks and savings.

But monetary policy is only one part of the story. Governments at all levels restrict the supply of housing by limiting building. That makes housing less affordable. The federal government also bids up demand for healthcare services while restricting the supply of doctors and hospitals, and it shields drug manufacturers from competition. That makes healthcare much more expensive. Meanwhile, Washington’s agricultural policy aims to prop up crop prices, which impacts the price of many foods. All this artificially drives up the cost of living.

That’s bad enough for autoworkers, but the Biden administration is also trying to force a transition to electric vehicles (EVs). For autoworkers building engines, transmissions, and exhaust systems, that’s a threat to their jobs. And because the ramp-up of EV production is driven by politics rather than consumer demand, the transition is set to hurt all workers who rely on cars.

Considering all that, it is obvious why autoworkers are frustrated with their financial situation. But unfortunately, their justified anger has been hijacked by another source of their problems, the UAW.

Support for labor unions rests on an economic myth from the mid-eighteenth century. In short, it’s the idea that companies make profits by not paying workers the full value of their labor. Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk dismantled this socialist exploitation theory 139 years ago when he introduced time into the analysis. Companies pay workers in the present for labor services that may lead to saleable goods in the future. Because of the universal trait of time preference, the certainty of money now is often more appealing than the possibility of more money later, which is why so many people choose to sell their labor services on the job market.

Böhm-Bawerk’s insights are easy to see in auto manufacturing, where workers are paid up front to help build cars that will be sold later. Still, the flawed idea that profits signify wage theft caught on, and in 1935, autoworkers founded the UAW. The present strikes speak to the persistence of this myth.

Labor unions often appeal to worker solidarity, but in truth, they epitomize the exact opposite. Because as Murray Rothbard has shown, they can only raise wages for some workers by lowering the wages or eliminating the jobs of other workers. At the Big Three automakers, this can be seen in the heavy use of temporary and part-time workers, who are placed on a lower pay tier—the elimination of which is ironically a core demand of the UAW strike. But this situation is just what’s visible. All those who are blocked entirely from the jobs that would be available to them if not for the union remain unseen.

America’s autoworkers are right to be angry about their economic situation. But the restrictionist labor demands of the UAW are a distraction that will, at most, help some autoworkers at the expense of others. The real solution lies in ending union practices that unnecessarily pit workers against each other, ending the policies that force companies to produce things consumers don’t even want, ending the multitude of government programs and political privileges that artificially raise the cost of living, and ending the monetary system that destroys the value of workers’ paychecks and savings while propping up the financial class. Abolish all that, and the benefits will extend far beyond the auto industry.

This article was originally featured at the Ludwig von Mises Institute and is republished with permission.