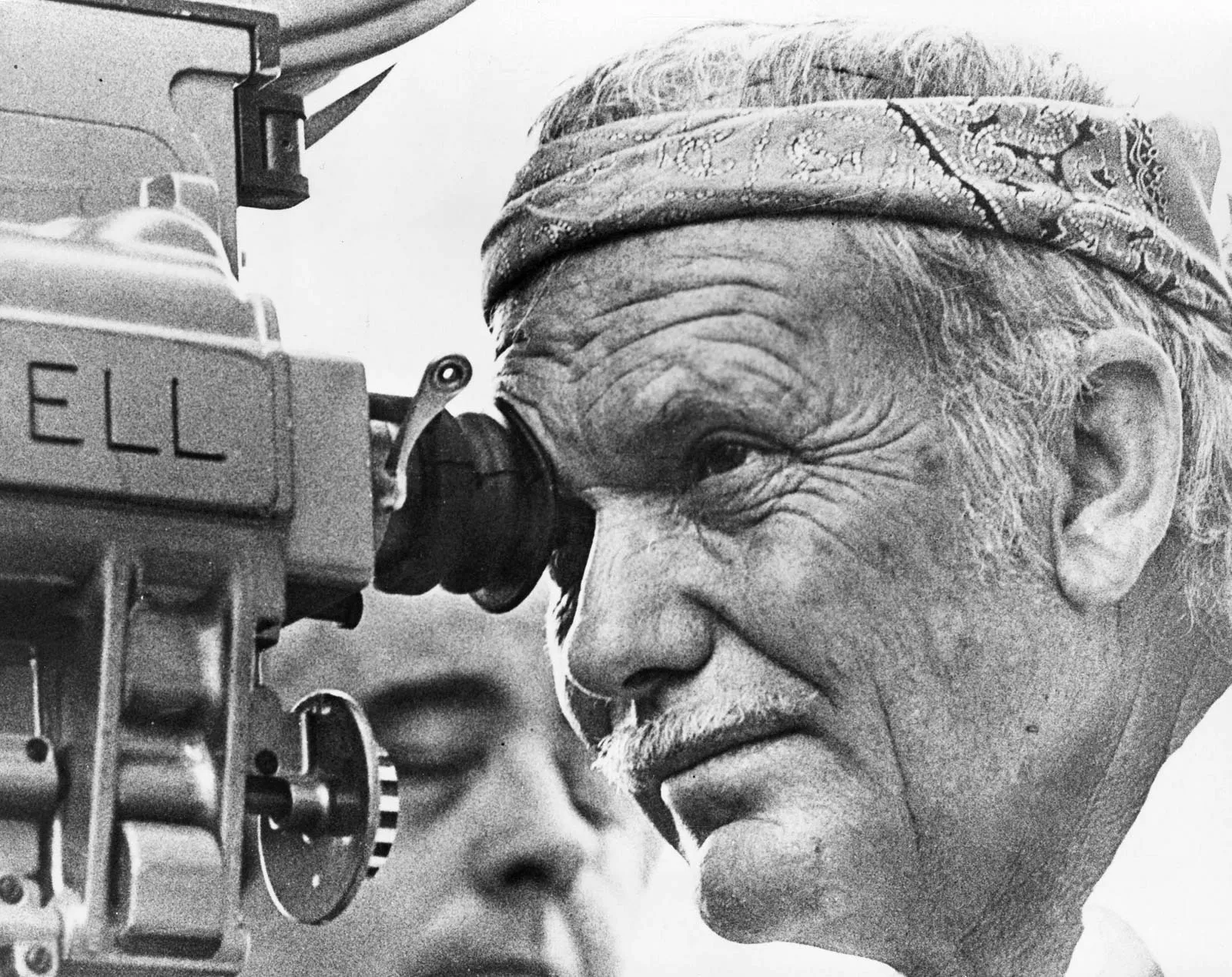

War movies have been popular since the early days of motion picture, often as means of propaganda to stir contemporary emotions and depict brave warriors of nation or faith locked in battle. War is a popular setting for story tellers, a stage for heroes and villains. The destruction and death is as much a prop as it can be a fellow character. Alongside the romantic war movies, some with an anti-war message emerged. In the 1960s and 70s, American film writer-director Sam Peckinpah gave us the misery of war with his own particular touch, specifically with The Wild Bunch and Cross of Iron.

There is a unique method to a Peckinpah film; slow motion that captures the violence and gore of death and destruction, followed by sudden rapidity encased in sound, with close ups on an actor expressing grit and determination to terror and pain. The viewer is shown the violence and its consequence. The structure is disorderly, exciting, perverse and once it has been digested, those characters that survive go on and will experience it again. The viewer is meant to see imperfect characters, to empathize and despise them as we accompany them. It is in knowing the human being inside the action and on the cinemascape that the viewer can share in the horror and action, whether via self insertion or as a voyeur.

The End to the Wild West

The Wild Bunch is set in 1913, long after what many would consider the prime period for the wild west. Featuring a gang of veteran outlaws that head to Mexico for one last job, the Wild Bunch’s redemption is in who their enemy becomes in the final showdown: a corrupt military led by a Mexican general that rules over a small town. Much like The Magnificent Seven it is a film about a few that take on a superior bully. The film’s climax is of a violent shootout that is both brutal, cinematic majesty and warfare all the same.

Peckinpah had previously made several other Westerns, each hitting the standard tropes of the genre, although his often depicted regret in his characters. It’s a human complexity that can be found in reality, especially during war. The wild west after all was a war, one between the civilized and the supposed savages, individuals resisting a conforming society and even that as fought between nations. The Wild Bunch begins with the protagonists dressed as U.S. Army soldiers on their way to rob a bank. A former gang member is hiding above in a rooftop with a thuggish pose, and below him the townspeople go about their day. The protagonists are polite and friendly as they help an old lady cross the street. But once inside the bank they become ruthless and determined.

Once the shootout commences the Wild Bunch and the posse exchange bullets as the townsfolk become insignificant cover or objects that now scatter the battlefield. Life and death is instant or painfully slow in a Peckinpah film. He always reminds the viewer that violence is unpleasant. The film’s heroes are not nice men, just men who are surviving, filled with regret and isolated outside of their own company. Those killing one another have more in common than the civilians around them. Peckinpah takes effort to depict the cruelty of the world, as children torment scorpions and ants, oblivious to the violence between men nearby.

Unlike other westerns, The Wild Bunch does not romance the outlaw or the frontiers that by 1913 have dwindled away. Classic repeater rifles and six shooters are matched by Maxim machine guns, Mauser bolt action rifles and Colt automatic pistols in a mesh of genres. Peckinpah claimed that he wanted the audience to know what it was like “to be gunned down.” So the sound effects and squibs needed to seem consequential. What Peckinpah shows is bloody and explicit, perhaps indulgent in moments.

The film ends in a dusty shootout between relics of the wild west and Mexican soldiers. A year after the film’s setting, in civilived Europe, millions of men would go to war for their imperial masters in one of the most gory and destructive conflicts of human history. Not even Peckinpah could write such madness of human tragedy sparked by a 19-year old murdering an elderly, married couple that would lead to the death of millions. Films need to make sense, reality not so much.

In the final battle, Pike (played by William Holden) mans a captured machine gun, killing many Mexican soldiers. He in turn is shot by a boy soldier. Rushing to his aid is Dutch (played by Ernest Borgnine), with six shooters in hand only to also be gunned down by the Mexican soldiers. Both men collapse in blood in desperate slow motion.

The film ends with the viewer seeing each of the now dead Wild Bunch in scenes from earlier in the film, each laughing in those lighter moments. The film’s men, fragile and courageous, were adventurers that shared a bond. And now they’re dead. When the film was made in 1969, thousands of men were fighting in South East Asia. The difference was that the Wild Bunch fought for themselves, feral relics against the army of a nation state. Perhaps in modern times they would be called terrorists, insurgents, or militants, though when it is red blooded Americans fighting as outlaws, such terms are seemingly misplaced.

Above all it is a film about honor and the stubbornness of men who abide by a code, even in a complicated world that has no place for such nobility. Though outlaws and displaying vestiges of the prime era of wild west villains, the men that make up the Wild Bunch are honorable and loyal. Dedicated to each other, brothers in a place where nature and man want them dead. As most soldiers do, they fight for the fellow that they laugh with and sleep alongside, while the abstracts beyond the battlefield are distant. After taking that final walk into certain death, the outlaws die bravely as soldiers.

Where Iron Crosses Grow

In 1977 Peckinpah directed Cross of Iron, a World War II film shown from the side of German soldiers trapped on the Eastern Front in 1943. Based on Willi Henrich’s book The Willing Flesh, it steers away from the source material in a lot of areas and becomes an audio-visual story that only Peckinpah could lead. The film’s setting is a horrible reality of mortar fire, mud, unclean conditions, and bullets. James Coburn plays Steiner, a veteran soldier and leader of grisly men who have no love for their Nazi masters. The soldiers have more in common with their opposite number, despite the brutal fighting, than they do their governments. Soldiers conscripted to fight for an ideology that they perhaps neither understand or even like but are ever crucial for its survival.

The film starts with the black and white reels of Nazi propaganda footage, children sing in optimistic and patriotic notes until eventually the promise of a statist Germanic utopia is interspersed with the grim realities of war. The film changes to color as we see the platoon of protagonists in a forest, intercut with images of Hitler and his devoted parading in gaudy uniforms with regalia and flags proudly raised. Soon we see our heroes snuffing out Soviet sentries with knife, garrote, and bare hands. The protagonists are men of deadly deed, like the Wild Bunch they know the craft of killing and though they do not do it for loot, Steiner’s platoon kills for survival.

Cross of Iron interjects the violent action scenes with characters discussing ideology and philosophy. Maximilian Schell plays Captain Stransky, an aristocratic Prussian officer who is neither Nazi or the common man, and who butts heads with Steiner. Despite his class and rank, he’s jealous of his subordinate. Steiner had previously won the Iron Cross, a medal for bravery, for saving lives while under fire. Stransky wants such a medal so that he may return home to his family proud and proven as a man. To Steiner it is a meaningless and worthless piece of metal, but to Stransky it is the reason he requested transfer from a lavish posting in Paris to the trenches of the Eastern Front.

Early on Steiner and his platoon capture a Soviet boy soldier and despite orders to murder all prisoners, they keep him fed, clothed, and hidden. The boy is the face of innocence along with a recent arrival, teenage soldier Dietz. Steiner attempts to set free the boy prisoner who is subsequently gunned down by his fellow Soviets moments before a battle where Steiner is wounded. The likeable young platoon Lt. Meyer is killed leading a counter attack. Afterwards Stransky attempts to claim credit for the actions of Meyer, naming Steiner as one of his witnesses. Steiner does not lend his support.

Colonel Brandt (played by James Mason) and his unhealthy adjutant Captain Kiesel (played by David Warner) are both pragmatic and sympathetic to Steiner. In another attack Steiner and his platoon find themselves behind enemy lines, Stranky having sacrificed them to the Soviets. While behind enemy lines Steiner and his men come across Russian female soldiers, where the romantically naive Dietz allows himself to be stabbed and a brute of a man loses his genitals while attempting to rape another. Steiner leaves the women along with his wounded soldier.

Returning to their lines, most of Steiner’s men are gunned down by Stransky’s aid, Lt. Triebig, who in turn is killed by Steiner and his survivors. Moments before his death, Triebig insists that he was ordered to do so. Among the madness of war, Steiner leaves the survivors of his platoon to lead Stransky into battle. “I will show you how a true Prussian officer fights,” Stransky promises, to which Steiner replies, “Then I will show you where the Iron Crosses grow.” While convalescing, Steiner had fallen in love with a nurse but he left her to return to the front lines to be with his men. A woman’s love is now a distant feeling for Steiner, who returns to battle alongside a man he hates.

Despite their deep conversations and intellectual sparring the men in the film are killers. They may hold a variety of beliefs as individuals that condemn the Nazi ideology, but they serve and kill for it. As men they may debate class and nobility but fight and die as equals when under attack. In the moments before carnage and the collectivist brutality of warfare, the men in Cross of Iron quote Clausewitz and Bernhardi with sarcasm and discuss the morality of homosexuality. But it is their deeds that exhibit their true character, killing for masters that they admit to hating and fighting a war that they do not believe in. Should the cameras transport the viewer across the battlefield into the Soviet camp we may find men of similar contradiction.

War is not glorious. Peckinpah wants us to know that. To witness violence with an uncomfortable indulgence is a reminder that a beast resides inside us all. Peckinpah wants us to love horrible men, to share with them and to bear witness to their deeds, even cheer for them. In fiction this is uncomfortable to admit but in life it is done without thought. Peckinpah gives us intimate glimpses into his stories, helps us to understand that the goodies do evil and bad men have reasons. Unlike romanticized war films, it is complicated. Many of us view the real world with a immature simplicity, ignoring the vulgar nuances of war and violence. It is how the process of war is often repeated. War has far too many sequels and we know they never get better over time.

“Do not rejoice in his defeat, you men. For though the world has stood up and stopped the bastard, the bitch that bore him is in heat again.”- Bertolt Brecht